While cataract surgery has become an incredibly safe outpatient procedure, it’s still surgery, and more than 738,000 surgical site infections occur every year involving outpatient surgery patients in the United States.1 With the aging baby boomer generation, the number of cataract surgeries is expected to rise, and clinicians must be prepared to handle the possible increased prevalence of complications. Two in particular—toxic anterior segment syndrome (TASS) and endophthalmitis—are often confused and pose significant risk if they arise.

Both can present early in the post-op period and share similar symptoms such as decreased visual acuity, redness and pain. The pain is usually mild with TASS but is often a deep ocular pain with endophthalmitis. Signs can be similar as well, including hypopyon, anterior chamber reaction such as fibrin formation and corneal edema. Endophthalmitis may show a vitritis and loss of red reflex.

While they can present with similar signs and symptoms, they have different etiologies and treatment paths—one of which requires swift changes to the surgical protocol and prompt reporting to state and local health departments.

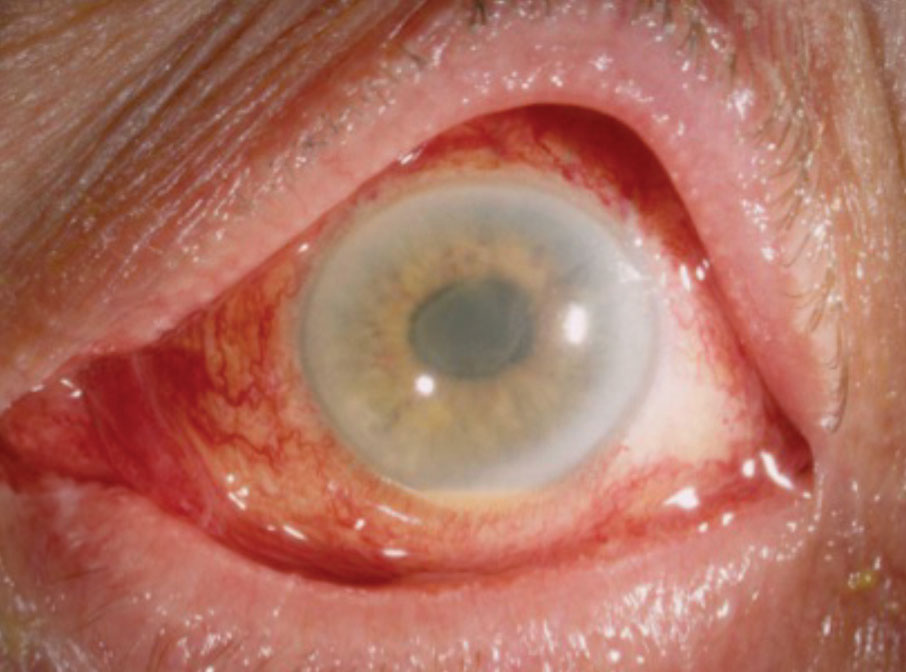

|

| Diffuse limbus-to-limbus corneal edema and anterior segment inflammation noted in a patient with TASS. Reprinted with permission from Deschênes J.11 |

A Toxic Situation

TASS occurs when toxic substances enter the anterior chamber and cause a sterile, noninfectious postoperative inflammatory response. Signs and symptoms of TASS present within 12 to 24 hours of cataract or refractive surgery and can include hypopyon, fibrin formation in the anterior chamber, corneal edema, irregular pupil, decreased visual acuity, mild pain and redness. Cellular necrosis and apoptosis occur, resulting in acute postoperative inflammation. The toxic substances break down the corneal endothelial junctions, causing the viable remaining cells to spread out over the damaged area in an effort to maintain the endothelial pumping system. If the remaining functional cells are unable to compensate for the loss, it can cause permanent corneal edema. Due to its inability to regenerate and replace dead cells, the corneal endothelium is often the most damaged structure. If the trabecular meshwork is damaged as well, it can cause decreased aqueous outflow, peripheral anterior synechiae and increased intraocular pressure.2

Four situations can lead to TASS:2

1. Inadequate sterilization of instruments. To avoid this concern, manufacturers of reusable handpieces recommend the instruments be flushed with 120cc of sterile de-ionized or distilled water.

2. Enzymes and detergents remain on cleaned instruments. This can be especially problematic with multi-specialty surgical centers that use enzymes and detergents generously to clean off tissue left on surgical instruments from several types of surgery. Any residue that remains on the instruments from this cleaning process can cause inflammation. Better education can help multispecialty surgical centers and hospitals understand that ophthalmic surgery rarely leaves tissue on instruments, and the use of these detergents and enzymes, which can be a cause of inflammation, may not be necessary.2

3. Endotoxin contamination during instrument sterilization. Even though gram-negative bacteria, which can reside in water baths and autoclave reservoirs, are killed during autoclaving, heat-resistant endotoxins from the bacteria can remain on instruments. The water used for these cleaning procedures must be changed regularly to avoid this complication.

4. Preservatives from products and medications. Products used during intraocular surgery, and intracameral drugs and balanced salt solutions used in the anterior chamber, must all be preservative-free.2 Preservatives or stabilizing agents used in ophthalmic solutions can be toxic to the corneal endothelium, leading to TASS.

The most common preservative is benzalkonium chloride. While this product is relatively safe when used on the ocular surface, it can cause corneal edema and endothelial cell damage when it enters the anterior chamber. Stabilizing agents such as bisulfate are also toxic to the corneal endothelium if it enters the anterior chamber. This agent is often found in epinephrine and balanced salt solutions. Any changes in pH, osmolarity or ionic composition of balanced salt solutions can also cause inflammation and damage to the corneal endothelium.3

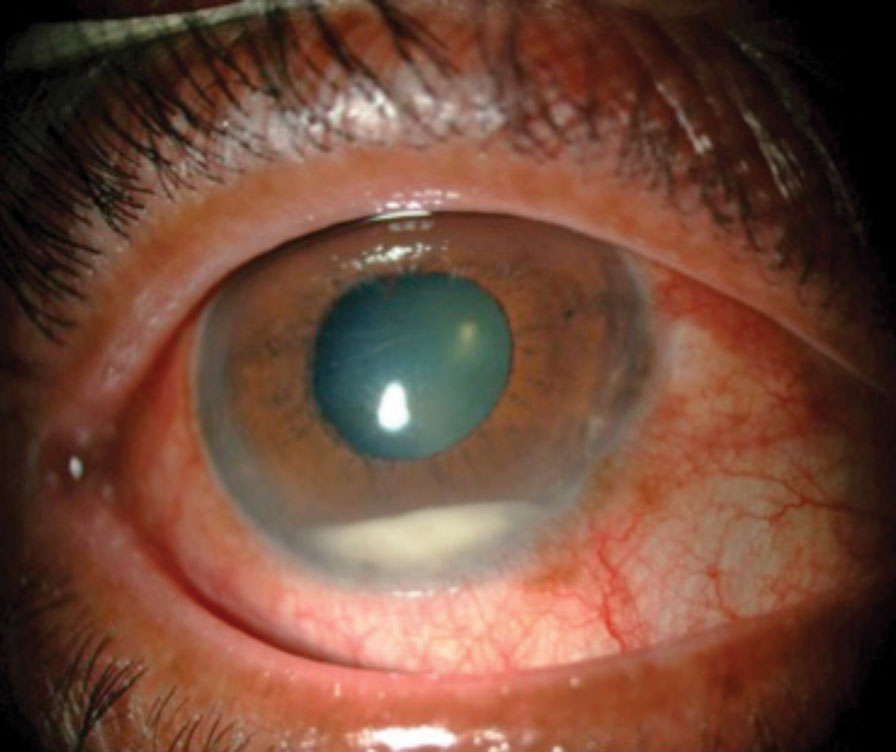

|

| Anterior chamber inflammation with hypopyon. Reprinted with permission from Chaudhry IA, et al. |

Tales of Contamination

Several products containing preservatives and other additives have been linked to TASS:

In December 2017, the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery (ASCRS) published a clinical alert regarding intraocular use of epinephrine to maintain mydriasis during cataract surgery. According to the alert, in January 2017 PAR Pharmaceutical began shipping a new formulation of epinephrine that contained 0.457mg of sodium metabisulfite and 2.25mg of tartaric acid per ml. While there is no published data or experience with intracameral administration of solutions containing tartaric acid, ASCRS had become aware of several reports of TASS associated with inadvertent use of the PAR epinephrine.3

Since then, the indication of use and maintenance of mydriasis during intraocular surgery has been removed from the product’s prescribing information. The 30ml bottles of epinephrine are clearly labeled “not for ophthalmic use,” although the 1ml single-use vials are not.4

Some products contain 0.1% bisulfite, which is used to improve stability by delaying the oxidation of the active substance. This agent can cause damage to the corneal endothelium. Ideally, preservative-free and bisulfite-free (PFBF) epinephrine is preferred, although corneas exposed to 0.05% sodium bisulfite have not shown any functional or structural damage to the corneal endothelium.4

In 2005, seven surgery centers across six states experienced a TASS outbreak related to a balanced salt solution contamination.5 Of 112 patients diagnosed with TASS from July 19, 2005 through November 28, 2005, 89% had been exposed to a single brand of balanced salt solution, AMO Endosol, manufactured by Cytosol Laboratories and distributed by Advanced Medical Optics.5 No significant breaks in sterile technique or instrument reprocessing occurred. Fourteen balanced salt solution lots were tested and five had elevated levels of endotoxin. The product was recalled, effectively containing the outbreak.5

Another uptick of TASS occurred in October 2006 at a 25-bed community hospital in Maine.6 The facility’s ophthalmologist noted increased inflammation and decreased visual acuity in eight out of 10 cataract surgery patients in one day.6 To prevent further cases, the surgical team suspended surgery and implemented these changes: switched the epinephrine to a preservative-free formulation; began changing the ultrasonic bath solution used to clean surgical instruments twice a day instead of once; used medications with different lot numbers for future surgeries; used personnel with more experience with the ophthalmologist; had the manufacturer inspect the autoclave to ensure it was functioning normally; changed the topical iodine antiseptic to single-use vials; and began using a new phacoemulsification tip with each new patient.6

With these changes in place, the ophthalmologist performed cataract surgery on four patients the following week—and all four developed TASS. The team suspended cataract surgery again and made further adjustments to the protocol: new cannulas for each procedure; a new lot of balanced salt solution; rinsing equipment removed from the ultrasonic cleaning bath with sterile distilled water instead of tap water; and discontinuing use of enzymatic cleaner in the ultrasonic bath. In addition, they performed an endotoxin test on the solution from the ultrasonic bath, which came back positive. Patients who underwent surgery following these changes all had successful surgery.6

|

| This patient has corneal striae and folds associated with TASS. Photo: Nick Mamalis, MD |

Control and Report

Once an infectious etiology has been ruled out, patients should start aggressive topical anti-inflammatory therapy with prednisolone 1% or similar steroid every hour, with daily monitoring for resolution of anterior chamber inflammation, corneal edema and intraocular pressure control.

In mild cases, patients usually improve quickly with no permanent damage. Moderate cases usually resolve within three to six weeks with possible residual corneal edema or damage. Severe cases can cause permanent damage leading to corneal transplant, cystoid macular edema, permanently dilated pupil and glaucoma due to damage to the trabecular meshwork.2

TASS outbreaks should be reported to both state and local health departments. Outbreak investigation assistance can be obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion. The Intermountain Ocular Research Center at the University of Utah and Emory University Eye Center can both assist with prevention and treatment. TASS cases associated with a certain product can be reported to the Food and Drug Administration’s Medwatch Program.2

Avoiding PreservativesCurrently, only a few manufacturers produce PFBF epinephrine. Belcher Pharmaceutical, a small company in Largo, Fla., produces PFBF, and Imprimis Pharmaceuticals makes a non-preserved, methylparaben-free epinephrine. Compounding 1.5% phenylephrine with 1.0% lidocaine without bisulfite is also an option. Omidria (Omeros) contains 1% phenylephrine and 0.3% ketorolac once diluted and helps to maintain mydriasis. Although American Regent changed their epinephrine formulation in 2012 to contain bisulfite, they planned to re-released the PFBF formulation in May 2018 after ASCRS reached out to stress the need for such a formulation.4 There has been no update by American Regent as of August 2018. |

Beware the Bugs

Endophthalmitis is an inflammatory reaction of the intraocular fluid and tissues as a result of a microbial organism entering the eye. Once bacteria enter the eye, they proliferate rapidly because the vitreous acts as an excellent medium, and initiates the inflammatory cascade.1

Over an eight-year period from 1994 to 2001, there were 1,026 presumed endophthalmitis cases out of 477,627 cataract surgeries—an incidence rate of 2.15 per 1,000.7

Signs and symptoms usually begin two to 10 days postoperatively and include decreased visual acuity, deep ocular pain and redness. The average acute onset is between 72 and 96 hours after surgery. Delayed-onset endophthalmitis generally occurs greater than six weeks after surgery. Slit lamp examination often reveals lid edema, hyperemia, corneal edema, anterior chamber cells and flare, keratic precipitates, hypopyon, fibrin formation, vitritis and loss of red reflex.1

Acute-onset endophthalmitis is usually caused by coagulase-negative gram-positive species such as Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococci, Enterococcus, and about 25% of all cases are caused by gram-negative species such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Delayed onset endophthalmitis is usually caused by Propionibacterium acnes, coagulase-negative and Corynebacterium species.1

Many of these organisms are part of the natural eyelid and nasal flora, and conditions such as blepharitis and nasolacrimal infections can increase the risk of endophthalmitis. Patients with systemic infections, diabetes and immunocompromise are also at a higher risk for infection. Bacteria can enter the eye via breaks in the sterile field from events such as improper draping and prepping of the surgical area, complex and prolonged surgeries, and inadequate sterilization of surgical equipment.7

Postoperatively, delayed wound healing can also lead to endophthalmitis. Posterior capsular tears, wound leaks, contaminated irrigation solutions and IOLs, surgeon experience, incision size and angle can all be risk factors for endophthalmitis.8

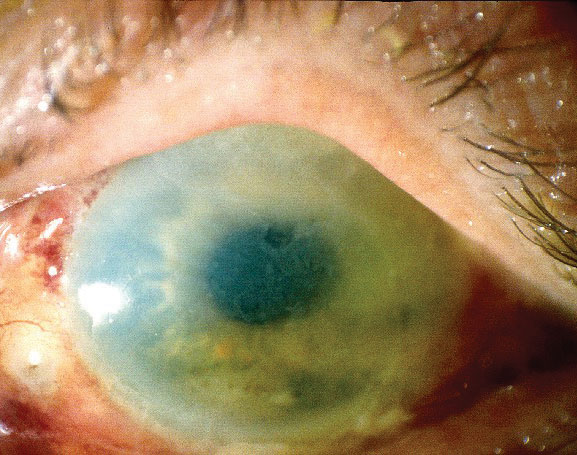

|

| TASS can cause both corneal edema and stromal haze, as seen here. Photo: Nick Mamalis, MD |

The Needle and Knife

Endophthalmitis treatment is guided by the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study (EVS), which recommends an injection of intravitreal antibiotics along with either a vitreous biopsy or PPV. The injections pass the blood-retinal barrier and often achieve successful therapeutic drug levels. Typically, treatment involves vancomycin (1mg/0.1cc) and ceftazidime (2.25mg/.01cc). Concomitant steroid use to decrease inflammation remains controversial.9

The presenting visual acuity is a good predictor of final visual outcome and often aids in determining the best course of treatment:

• Hand motion or better. Treatment usually consists of a vitreous tap and injection of intravitreal antibiotics. The vitreous fluid is sent for a gram stain and culture. If the vitreous is too dense and consists of inflammatory fibrin, an aqueous sample may be obtained via an anterior chamber paracentesis. Vitreous tap cultures are positive 56% to 70% of the time, while an anterior chamber paracentesis is positive in about 40% of cases.8

• Light perception. Treatment consists of a PPV with injection of intravitreal antibiotics. The vitrectomy allows for removal of the organism, reduction of vitreous fibrin and membranes that could lead to subsequent tractional retinal detachment and improved penetration of the antibiotics. Samples of the vitreous at the time of the vitrectomy are sent for gram stain and culture.

Patients with no improvement from a vitreous tap and injection should have a vitrectomy followed by repeated intravitreal antibiotic injection.8

The EVS shows that systemic antibiotic treatment has no benefit. While the antibiotics used in the study, ceftazidime and amikacin, have limited gram-positive coverage, newer fourth-generation fluoroquinolones have better efficacy and broader coverage when given systemically. Oral moxifloxacin, for example, can achieve therapeutic levels in the aqueous and vitreous in a non-inflamed human eye. A large randomized study would help to determine the efficacy of newer systemic and topical medications in the treatment of postoperative endophthalmitis.8

Optometrists are comanaging more cataract surgery patients as baby boomers continue to age. Although both are rarities, TASS and endophthalmitis are possible complications every OD must be prepared to diagnose and manage should it arise. Their similar presenting signs and symptoms may cause initial confusion, and recognizing and understanding the differences between the two conditions is the key to initiating timely and appropriate treatment and referral to save our patients’ vision.

Dr. Fluder practices at Williams Eye Institute in Merrillville, IN.

1. Progressive Surgical Solutions, LLC. TASS and Endophthalmitis. 2013. 2. Sabbagh MD, Omar Mekari. Update on Toxic Anterior Segment Syndrome. Rev Ophthalmol. March 16, 2007. 3. American Academy of Ophthalmology. TASS etiology. www.aao.org/focalpointssnippetdetail.aspx?id=35b758bf-71a0-4264-bdb6-62d4a7f5be12. Accessed January 14, 2018. 4. American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery. Clinical Alert: Intraocular use of epinephrine to maintain mydriasis during cataract surgery. December 13, 2017. 5. Kutty PK, Forster TS, Wood-Koob C, et al. Multistate outbreak of toxic anterior segment syndrome 2005. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34(4):585-90. 6. CDC MMWR Weekly. Toxic anterior segment syndrome after cataract surgery-Maine. 2006;56(25):629-30. 7. West ES, Ashley Behrens A, McDonnell PJ, et al. The incidence of endophthalmitis after cataract surgery among the U.S. Medicare population increased between 1994 and 2001. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(8):1388-94. 8. Abelson MB, Kennedy K, Lilyestrom L. Unraveling the mystery of endophthalmitis. Rev Ophthalmol. January 24, 2008. 9. Tewari A, Shah GK. Cataract complications: the retinal perspective. Rev Ophthalmol. August 16, 2006. 10. Chaudhry IA, Al-Dhibi H, Al-Rashed W, et al. Endophthalmitis: experience from a tertiary eye care center. IntechOpen. May 8, 2013. 11. Deschênes J. Toxic Anterior Segment Syndrome (TASS). Medscape. May 3, 2017. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1190343. Accessed January 8, 2019. |