|

Microbial keratitis (MK) is arguably the most acutely sight-threatening pathology in the optometric scope of practice. Reduced vision, need for surgery and loss of the eye are all possible outcomes, which can make MK management unsettling.

Once you suspect MK and have deduced which organisms you’re likely dealing with, you must decide whether to refer the case elsewhere or continue management based on your comfort level working with corneal ulcers and what will provide patients the best chance at a good outcome. If you choose to manage instead of refer, the first critical step in determining treatment is deciding whether you should culture the ulcer or not.

The Strategies

There are three basic approaches to culturing:

1. Culture (or refer for culturing of) all likely MK.

2. Culture (or refer for culturing of) likely MK on a case-by-case basis based on the size, depth and unusual historic risk factors of the ulcer.

3. Always treat likely MK empirically, culturing (or referring) only if empiric treatment fails.

While the first approach may prove time consuming and a bit foreign to many optometrists, the last approach can get you and your patient into trouble both clinically and medical legally. The second option is probably the best practice pattern, representing a compromise between risk and benefit. For case-by-case culturing, mnemonics and algorithms can help indicate when culturing is appropriate. These have to do with some combination of the size and depth of the ulcer, its proximity to the visual axis, extent of the anterior chamber reaction and any unusual features (which may include history).

A reticule on your slit lamp makes size measurement easy, but not all slit lamps have one. Holding a ruler close to the lesion can be difficult and inaccurate, and if you struggle with this, try to use the overall size of the cornea (usually 12mm) or the size of the patient’s pupil as a reference to compare with the ulcer.

Lesions greater than 3mm in diameter in any meridian (or ¼ of the corneal diameter) should be cultured or referred for culturing. Any ulcer that immediately threatens vision—either through direct involvement and opacification of the visual axis or from creation of irregular astigmatism when a post-infectious scar develops—bears culturing as well. Also, any ulcer with features (e.g., feathery margins, satellite infiltrates, pigmented infiltrates) or history (e.g., vegetative trauma) suggestive of a fungal etiology should be cultured, as fungal infections have a greater likelihood of leading to the need for surgery.1 If you opt to refer a case for culturing, hold off on antimicrobial treatment if the referral center can see the patient within 24 hours.

If you decide to culture the patient yourself, be aware of differences among various culture protocols. Pre-packaged culture swabs are the backbone of optometric culturing. However, while they are well suited for conjunctival culturing, they more accurately represent “culture-lite” rather than full culturing when assessing corneal infections.

Pre-packaged culture swabs can be effective with larger ulcers, but it can be nearly impossible to retrieve enough material to inoculate swabs when dealing with small or dry ulcers. Also, the transport soy broth sponge does not support all ophthalmic pathogens, and you cannot use these swabs to apply material to a microscope slide for gram staining purposes. The swabs are far too large for retrieving material from smaller ulcers, and the swab head, which is approximately 5mm, can often obscure your view of the ulcer, making it difficult to see what you are doing.

Better for full culturing services and plating media directly would be the platinum spatula, which allows for quick sterilization between gathering specimens, a sterile foreign body spud, a #15 Bard Parker blade (with a lid speculum placed) or moderate-gauge needle (with a lid speculum placed), though the last two increase potential handling concerns since they are sharp objects.

The Procedure

When gathering material, first instill a drop of anesthetic. Some argue against this approach because proparacaine can reduce your culture yield. This may be true, but a patient not allowing you to touch their cornea will reduce your culture yield even more. In an already painful eye, the chance of a patient allowing you to gather a corneal specimen without an anesthetic is close to zero, so help the patient help you by anesthetizing the eye.

|

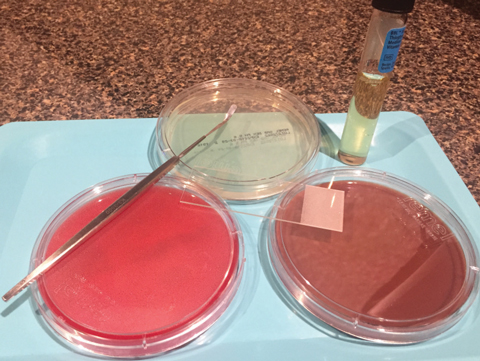

| Some standard cuturing tools include blood (red), chocolate (brown) and Sabouraud dextrose (clear/yellow) agars as well as thioglycolate broth (in test tube), a Kimura spatula and a gram staining slide. |

Once you have gathered the specimen, apply it to a liquid medium such as thyoglycolate broth—which is often best inoculated with a swab that can be broken off and left suspended in the media—or a solid agar-based media where the specimen is inoculated onto the surface in a series of concentric Cs. For full culturing services, multiple media will be inoculated; blood, chocolate and Sabouraud dextrose agar or inhibitory mold agar for fungus are the standard three.

When inoculating multiple media, make sure to either sterilize your specimen-gathering tool or use a new one between sample collections to avoid re-inoculating material back into the cornea at a different level.

Next, you can inoculate a light microscope slide with material for gram staining. Though gram staining has an even lower yield than culturing, it can provide faster information regarding the general features of your causative pathogen. Usually, these are ready to read within an hour when stat interpretation is requested.

Because culture media has a short shelf life, it’s not practical to keep a full complement stocked in your practice. Luckily, requesting media from a lab is usually quick since most outpatient microbiology labs have courier services available to deliver and pickup media. If you choose to culture yourself rather than refer out, establish a relationship with a lab prior to a corneal ulcer walking into your office so you can avoid potential administrative hurdles.

Once you’ve completed your culture, you will receive reports back from the lab at time intervals dependent on the media and what (if anything) is growing. Early culture results will usually be reported in one to two days, and again a week later. Fungal cultures will be read after a week and then again at a month. If growth exists, you can request sensitivity testing, which reports efficacy of various antibiotics to the isolates and is helpful in titrating the most effective antibiotic strategy.

With a sensitivity test, the antibiotics listed aren’t generally ones we use in eye care because sensitivity testing is derived from a systemic test. Microbiology labs run a standard minimally inhibitory concentration (MIC) test regardless of the origin of the infection. This is important for two reasons.

First, as a systemic test, the MIC test is concerned primarily with the safe systemic administration of antibiotics so it will not test for concentrations high enough that they could cause significant morbidity when dosed systemically. However, because we can safely achieve much higher corneal concentrations than are tested for and because effectiveness of all antibiotics is concentration dependent, we may occasionally achieve in vivo efficacy with an antibiotic that a given isolate in vitro has been determined to be resistant to. Said plainly, because of our ability to achieve high tissue concentration in the eye, sometimes we can have success treating with an antibiotic that MIC testing suggests won’t work.

The second reason the systemic origin of MIC testing is important is that one of our front-line antibiotics, besifloxacin, has no systemic equivalent and is not tested. This makes it difficult to have full confidence that besifloxacin will be effective if an isolate shows resistance to moxifloxacin on sensitivity testing, regardless of what 2009’s ARMOR study showed (that besifloxiacin was only slightly less effective than vancomycin when dealing with MRSA isolates).2

Due to both real and perceived barriers involved in culturing, empiric therapy is the primary treatment strategy used by most optometrists when managing corneal ulcers. For the majority of cases, this will be effective. However, when this approach is ineffective, it has potential to dramatically increase the chances of an ulcer requiring surgical intervention. To help avoid this outcome, perhaps a shift towards a more culture-forward strategy would be wise. I’ve never regretted the choice to culture, but I have managed ulcers that made me wish I gathered a culture prior to initiating therapy.

1. Prajna NV, Srinivasan M, Lalitha P, et al. Differences in clinical outcomes in keratitis due to fungus and bacteria. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(8):1-4. |