|  |

The advent of soft disposable contact lenses permanently altered the contact lens landscape, resulting in the decline of corneal gas permeable (GP) lens fitting. GP lenses are increasingly relegated to patients with complex prescriptions or high vision demands, and specialty designs such as custom soft toric, hybrid and scleral lenses are now widely available and steadily growing in popularity. Consequently, corneal GP lenses are often overlooked as a first choice.

Thanks to today’s technology, complications related to contact lens overwear and poor lens-to-cornea alignment can be identified early on to help avoid permanent corneal damage. It is important to be aware of common GP lens complications and understand how to troubleshoot in order to maintain good corneal health and lasting comfort.

Corneal Staining

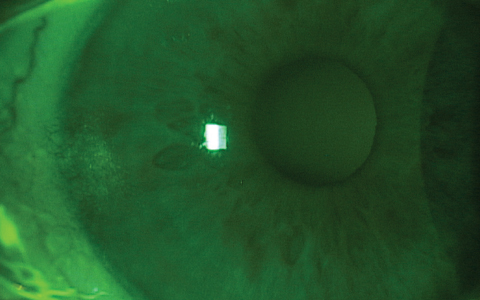

Epithelial punctate staining can occur during GP lens wear for several reasons. Peripheral corneal desiccation, particularly 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock staining, pertains to the area of the cornea not adequately resurfaced with tears (Figure 1). This can occur due to the contact lens fit, incomplete blink or the patient’s lid positioning.1

|

| Fig. 1. An example of 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock staining. |

If the lens has excessive peripheral edge lift or a particularly thick lens edge, the amount of tears swabbing the corneal surface is minimized due to the gap between the eyelids and cornea. This lid gap can also be caused by a low-riding lens or an incomplete blink. The same peripheral staining can occur if the lens has inadequate peripheral edge lift resulting in insufficient lens movement and minimal tear exchange.

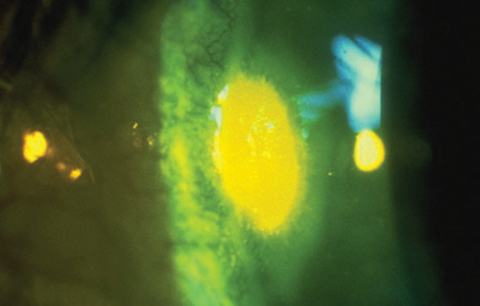

If not treated, the areas of desiccation can lead to coalesced punctate staining and, eventually, corneal thinning resulting in ulceration, neovascularization and scarring.1 The area of reversible peripheral thinning is referred to as a dellen (Figure 2). Patients may be asymptomatic in mild cases. In more severe cases, patients may complain of dryness, displacement of contact lenses, redness, lens awareness, light sensitivity and reduced lens wear time.1

Since 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock staining is often related to contact lens alignment, centration and movement are critical. If a lens is decentered inferiorly, reducing the center thickness or using a lenticulated design may help minimize weight.2 Flattening the base curve of a lens with excessive clearance will help with centration. Sometimes a larger diameter lens may be required for centering, but this may need to be coupled with thinning center thickness and reducing sagittal depth to avoid weighing down the lens.

If edge clearance appears excessive when examining with fluorescein and a cobalt blue filter, a steeper peripheral curve radius or a narrower peripheral curve width may be indicated. Also, if there appears to be lens adherence, the case may call for a flatter peripheral curve radius or a wider peripheral curve width. If the lens edge is excessively thick, consider thinning it to provide a closer lid-to-cornea alignment.2

Selecting a lens material with good wetting properties can help address corneal staining. Frequent lubrication with rewetting drops may also be beneficial and necessary to maintain optimal corneal health. If the peripheral corneal desiccation is related to partial or incomplete blinking, the patient may benefit from blinking exercises in conjunction with rewetting drops. Ultimately, if changing the lens fit and incorporating adjunct therapies does not resolve the corneal staining, the patient should be advised to minimize contact lens wear time or consider switching to other modalities such as piggy back lenses, soft contact lenses or scleral GPs.

|

| Fig. 2. Corneal dellen with fluorescein pooling. |

Vascularized Limbal Keratitis

A related condition known as vascularized limbal keratitis (VLK) occurs when corneal desiccation is further compromised by peripheral seal off of the lens edge.3 These lesions will show superficial staining. More advanced cases can result in vascularization, staining and an elevated opacified region.3 Patients may experience a significant decrease in lens wear comfort, a decrease in wear time and significant awareness of the VLK lesion.

VLK can be easily mistaken for corneal neovascularization, corneal dellen and phlyctenulosis.3 Corneal neovascularization usually takes longer to resolve than VLK, however, and is more rare in GP lens wear.3 Unlike VLK, corneal dellen will pool with fluorescein instillation but will not stain. Additionally, topography reveals a corneal depression in cases of corneal dellen instead of VLK’s staining elevation. VLK can be differentiated from phlyctenulosis by how quickly it regresses—VLK can regress in a few days, while phlyctenulosis will often persist for up to two weeks.3

Treating VLK revolves around eliminating the cause of desiccation and is usually related to lens fit or contact lens materials. If the lens fit is too tight, flattening the peripheral curves and base curve radius can be beneficial. Decreasing the diameter of the lens can also help eliminate a steep fitting lens.2 Reducing lens wear time and frequent lubrication is advised to eliminate peripheral desiccation. In more severe cases with corneal thinning or vascularization, practitioners should consider corticosteroid and antibiotic-steroid combination drops.4

|

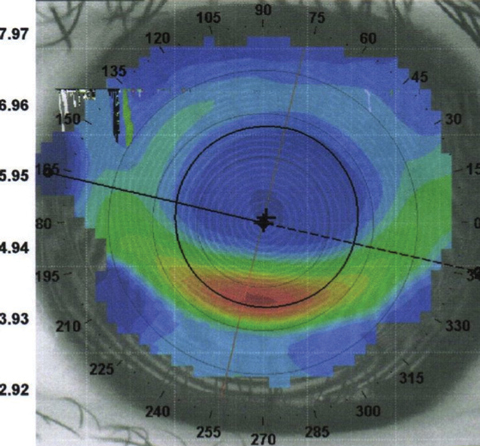

| Fig. 3: Corneal warpage due to an inferiorly decentered contact lens. |

Corneal Warpage

Both GP lenses and thick, stiff soft lenses can cause corneal warpage. Often, patients are unaware of the problem and continue to wear their lenses for extended periods of time.2 Before the advent of corneal topography, corneal warpage was generally described as a condition that included distorted keratometer mires with or without irregular astigmatism and reduced vision on post-lens wear refraction.5 Because of the increased use of topography, however, the definition of corneal warpage now includes central irregular astigmatism with a loss of radial asymmetry (superior flattening and inferior steepening), and a reversal of the normal flattening corneal contour.5

One cause of corneal warpage is an excessively steep base curve radius. This causes the lens to suction onto the cornea, creating an irregular corneal surface. To combat this, practitioners can flatten the lens base curve and peripheral curves to provide adequate tear exchange and lens movement.

Another cause is spherical GP lens wear in patients with 2.5D or more of corneal astigmatism. By not fitting a patient in an appropriate back surface toric design, topographical changes can occur over time.6

If a lens is riding high from a flat fitting lens, superior flattening of the cornea can occur with a steeper contour inferiorly. Depending on the degree of corneal molding, this can be misdiagnosed as keratoconus (Figure 3).5 In these cases, it is important to limit contact lens wear for a few weeks and retake imaging to ensure repeatability of findings.

In all corneal warpage cases, patients tend to rely on contact lenses to see clearly and experience spectacle blur.7 Irregular astigmatism may be evident on corneal topography and irregular findings on manifest refraction. Patients may complain of halos or distorted vision that is more evident with glasses. To resolve this, practitioners should instruct patients to take a break from contact lens wear and refit them starting with baseline corneal findings.

It is important to identify corneal staining, VLK and corneal warpage early in order to provide lasting GP lens comfort and avoid long-term corneal damage. Working with GP lenses may appear daunting at times, but understanding simple troubleshooting techniques will allow for continued success.

1. Businger U, Treiber A, Flury C. The etiology and management of three and nine o’clock staining. Internat cont lens clin. 1989;16(50):136-9. |