First described by Australian ophthalmologist Thomas Spring, MD, in 1974, giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC) is an exogenous ocular inflammatory condition commonly seen in contact lens wearers and patients with ocular prosthesis or exposed sutures following surgery.1 Often mislabeled as an environmental allergic reaction, GPC is in fact the result of papillary changes in the tarsal palpebral conjunctiva of the eye as part of an immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated hypersensitivity reaction to the presence of the lens.

The move to daily disposal of contact lenses in recent years has led to a marked decrease in papillary responses of the conjunctiva—but only for contact lens-related presentations. Other types of papillary conjunctivitis commonly associated with (or confused for) GPC include vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) and atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC). This article will review the manifold allergic reactions that can include a papillary response.

’Tis the Season

VKC is a chronic allergic conjunctivitis that affects children and young adults, especially boys, typically between the ages of six and 18.2

Patients with VKC often have a family or medical history of atopic diseases, such as seasonal allergies, asthma, rhinitis and eczema. Atopic disease may be more common in young males. Common symptoms include itching, photophobia, burning, redness, mucus discharge and tearing; often, the presentation follows a seasonal pattern, with the worst symptoms occurring in the spring and early summer.2

Note, however, that VKC is not solely an IgE-mediated disease, since it is not associated with a positive skin test or RAST in 42% to 47% of patients.2

Clinically, cases of VKC are classified as either limbal, palpebral or mixed. The palpebral form typically presents with enlarged papillae primarily along the upper tarsal conjunctiva, superficial keratitis and conjunctival hyperemia; the latter tends to be pink in color rather than red, as in more acute forms of conjunctivitis.

|

|

|

|

|

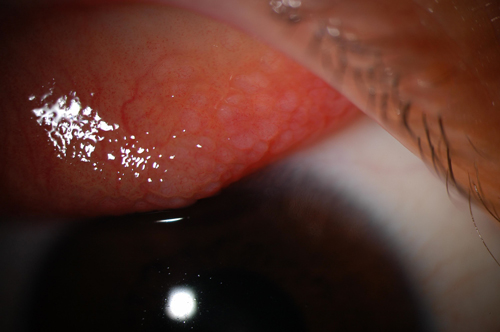

Fig. 1. Giant papillary conjunctivitis on superior palpebral conjunctiva. |

In the limbal form, believed to be more common in dark-skinned individuals from Africa and India possibly due to the hot climate, the palpebral conjunctiva exhibits a papillary response without formation of giant papillae. Instead, Horner-Trantas dots, which are focal collections of eosinophils, present as limbal papillae associated with epithelial infiltrates. Superior punctate keratopathy exists in both forms of the disease.

In severe cases, punctate lesions can coalesce into a sterile shield-shaped ulcer, known as a vernal ulcer, located between the middle and upper third of the cornea.

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis is typically treated using combination eye drops that act as both an antihistamine and mast cell stabilizer. These antihistamine/mast cell stabilizers can be prescribed either for seasonal allergies, or year-round if VKC is a perennial disease, without risk of any side effects of long-term use. Regardless, treatment should be initiated as soon as VKC is detected to control the condition as quickly as possible.

In more severe cases of VKC, antihistamine/mast cell stabilizers lack the ability to treat the disease, so topical steroids may be needed instead. Because the dosage and strength of topical steroids vary, they should be selected carefully. A study comparing prednisolone, fluorometholone and loteprednol found no significant differences between the groups with regards to signs and symptoms—all showed gradual improvement. However, pannus formation in the fluorometholone group and a significant increase in intraocular pressure in the prednisolone group were both observed.3

Topical cyclosporine may also be used to treat VKC. A six-month prospective study of 2,597 patients in Japan correlated a significant decrease in symptoms with the use of a topical cyclosporine.4 In fact, 30% of the patients using topical steroids were able to discontinue them within three months. Adverse drug reactions—eye irritation being the most common—were found in 7.44% of patients.

In a separate study conducted in Italy, 156 children with VKC were given either a 1% or 2% concentration of cyclosporine two to four times daily and monitored over two to seven years. Overall, ocular objective scores significantly improved, suggesting both concentrations of cyclosporine eye drops are safe and effective for long-term treatment of VKC.5

Recognizing AKC

AKC, first reported in 1952 by Michael Hogan, MD, is a relatively uncommon but potentially blinding condition that occurs in 20% to 40% of people with atopic dermatitis. AKC is also closely associated with concomitant eczema (95%) and asthma (87%), and is more prevalent in men than women, with onset ranging from late teens to 50 years of age.7

In AKC, both Type I (immediate) and Type IV (delayed) hypersensitivity reactions contribute to the inflammatory changes of the conjunctiva and the cornea. During exacerbations, patients have increased tear and serum IgE levels, increased circulating B-cells and depressed T-cell levels. Thus, common ocular symptoms of AKC (with little or no seasonal variation) include itching, tearing, ropy discharge, burning, photophobia and decreased vision.

AKC may also affect the eyelid skin with eczema (e.g., dermatitis and keratinization). Additionally, blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction may be present, as well as chemosis of the conjunctiva with a papillary reaction that is more prominent in the inferior tarsal conjunctiva, unlike the reaction in VKC. Horner-Trantas dots, however, are rarely present. With chronic inflammation, fibrosis or scarring of the conjunctiva may result in symblepharon. Early in AKC, corneal staining may be present; as AKC progresses, corneal neovascularization, stromal scarring and ulceration may occur.

There is also a strong association between herpes simplex keratitis and AKC. Additionally, keratoconus may be associated with AKC, which may be associated with chronic eye rubbing.

AKC may also ultimately result in permanently decreased vision or blindness from corneal complications, including: chronic superficial punctate keratitis, persistent epithelial defects, corneal scarring or thinning and keratoconus.8 Cataracts and symblepharon may also occur.

Similar to VKC, AKC treatment options include topical antihistamine/mast cell stabilizers, topical steroids, topical cyclosporine and other immunosuppressives like tacrolimus and pimecrolimus.9,10 In addition, oral antihistamines and steroids can help provide prompt symptom relief.

What is GPC?

Also known as contact lens-induced papillary conjunctivitis (CLPC), this condition results from an immunological response in combination with mechanical trauma. It is typically brought on by eyelid movement over a foreign object, such as a contact lens, that may have pollen, bacteria or other allergens trapped underneath it.

In CLPC, non-specific papillary inflammation occurs on the superior tarsal conjunctiva. Papillae increase in size and progress in severity as the disease advances to the characteristic large papillae (greater than 0.3mm in diameter) on the tarsal conjunctiva.12 Occasionally, there is inflammation of the bulbar conjunctiva, and punctate staining on the cornea may be present.

GPC from contact lens wear is most often attributed to the frequent movement of the lens edge against the eye during blinking. On average, young men blink 9,600 times per day, while young women blink 15,000 times. With age, the blink rate increases to 22,000 times per day.16 This can sometimes lead to chronic irritation that results in inflammation.

The biofilm on a contact lens is another factor influencing GPC development. Changing the polymer of the contact lens in a patient with GPC can decrease the chance of GPC recurring, as deposits on the surface of a contact lens depend on the type of lens.17 For example, higher water content contact lenses develop more deposits than lenses with lower water content.21 Protein deposits, specifically, depend on polymer content, structure and charge.22,23 Studies have documented that lenses with both high water content and ionic properties have the highest amount of protein deposits.21,24,25

For patients with regular astigmatism and a normal cornea, it may be possible to change the type of lens material. For patients with irregular astigmatism such as keratoconus or post penetrating keratoplasty, however, it may not be possible to change the material. In these instances, peroxide disinfection solutions can be useful. Also, use of an alcohol-based cleaner for 30 seconds daily (Miraflow, Novartis) or a two-component cleaner with sodium hypochlorite and potassium bromide (Progent, Menicon) for 30 minutes one to two times a week can be effective.

GPC’s Presentation

Contact lens-associated GPC can present any time from a few weeks to several years after commencing lens wear. It is typically bilateral, but may be asymmetric in presentation. Symptoms of GPC are associated with all types of contact lenses (i.e., GP, hydrogel, silicone hydrogel, piggyback, scleral, prosthetic); however, daily disposable lenses may be the best lens option, as increasing contact lens replacement frequency can also decrease the incidence of GPC.17

Symptoms include increased mucus discharge, blurred vision, foreign body sensation, excessive contact lens movement, decreased contact lens tolerance and reduced contact lens wearing time.13,15

Shield ulcers are absent, unlike in VKC.

Itching, an indication of true allergic disease, is also typically not present in GPC. However, allergies do play a role: in a study by Donshik, concurrent allergy was present in over 26% of patients with GPC, and those with allergic conditions had more severe signs and symptoms than non-allergic subjects.14

Recent research illuminates many mediators of inflammation in GPC. Patients have been shown to have elevated levels of chemokines and cytokines such as IL-8, IL-6, IL-11; macrophage inflammatory protein-delta; tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 macrophage-colony stimulating factor; and monokine-induced gamma interferon, eotaxin, pulmonary and activation-regulated CC chemokines.18 Additionally, membranous epithelial cells (M-cells) and B-lymphocytes play a role in the pathogenesis of CLPC for the binding and translocation of antigen and pathogen.19

Treatment and Prevention

Since the pathophysiology of GPC is complex, with a combination of both immune and mechanical mechanisms, understanding these mechanisms is important in both treatment and prevention of GPC.17

To manage GPC currently, it is prudent to focus on prevention; thus, identifying and removing the cause, such as lens deposits contributing to an inflammatory response, is fundamental to resolving GPC. Additionally, because soft contact lens-associated GPC is more common than GPC stemming from gas permeable lens wear, changing to a GP material can help eliminate GPC.14

Modification of the contact lens edge can also help prevent or eliminate GPC. Patients should also be advised of proper lens care habits and hand hygiene, as they can help prevent surface debris on contact lenses that might lead to GPC.

More frequent replacement of contact lenses, specifically daily disposable contact lenses, can also reduce the incidence of GPC. In a study evaluating 47 contact lens wearers published in 1999, GPC was present in 36% of patients whose contact lens replacement schedules exceeded four weeks compared to 4.5% of those who changed contact lenses more frequently than once every four weeks.20 However, GPC still limits the ability of some patients to wear contact lenses, even despite more frequent replacement intervals and new lens materials.

Treating the Problem

Temporary discontinuation of contact lens wear for one to three weeks may be sufficient for symptoms of GPC to diminish, although papillae may take months to resolve. Transitioning to a more frequent replacement contact lens is helpful to minimize the incidence of GPC once the patient resumes contact lens wear.

Topical steroids such as Lotemax (loteprednol etabonate, Bausch + Lomb) can be used to treat the inflammation associated with more severe GPC. However, long-term use of topical steroids can have potential side effects such as elevated intraocular pressure, glaucoma and cataracts. Antihistamine/mast cell stabilizers may also be used; however, these are of limited usefulness, as GPC is not primarily a mast cell-mediated response like seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. First and foremost, however, it is important to discontinue contact lens wear until GPC improves.20 If it is not possible to discontinue lens wear altogether, for example in instances such as keratoconus, lens wearing time should be reduced as much as possible until GPC improves.

In suture-related GPC and scleral buckle exposure, a localized area of GPC on the superior tarsal conjuctiva overlying the offending suture is diagnostic for GPC. Mucous discharge may be attached to loose, exposed sutures. Treatment of suture-related GPC is removal of the exposed sutures.

GPC related to prostheses is a combination of Types I and IV hypersensitivity, in addition to chronic trauma to the upper tarsal conjunctiva during blinking. Mucus coating may form on the prosthetic device. The treatment approach in GPC related to prostheses is to increase the frequency of removal, cleaning and polishing of the prosthesic device. Antihistamine/mast cell stabilizers may also be used if indicated, but should not be the primary treatment.

Now that we understand that GPC is an inflammatory condition that results from repetitive mechanical irritation, not a conventional allergy, we can use our tools in clinical practice to better diagnose and prevent GPC.

Dr. Barnett is a principal optometrist at the UC Davis Medical Center, where she specializes in anterior segment disease and specialty contact lenses. She lectures and publishes extensively on dry eye, anterior segment disease, contact lenses, collagen crosslinking and creating a healthy balance between work and home life for women in optometry. She serves on the boards of Women of Vision, the Gas Permeable Lens Institute and the Scleral Lens Education Society.

1. Katelaris, CH. Giant papillary conjunctivitis-a review. Acta Ophthalmol Scand Suppl. 1999;(228):17-20.

2. Bonini, S, Coassin, M, Aronmi, S, et al. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Eye (2004) 18, 345–351.

3. Oner V, Türkcü FM, Tas M, et al. Topical loteprednol etabonate 0.5% for traetment fo vernal keratoconjunctivitis: efficacy and safety. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2012 Jul; 56(4):312-8.

4. Takamura E, Uchio E, Ebihara N, et al. A prospective, observational, all-prescribed-patients study of cyclosporine 0.1% ophthalmic solution in the treatment of vernal keratoconunctivitis. Nihon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 2011 Jun;115(6):508-15.

5. Pucci N, Caputo R, Mori F, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of topical cyclosporine in 156 children with vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2010 Jul-Sep;23(3):865-71.

6. Foster CS, Calonge M. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. Aug 1990;97(8):992-1000.

7. World Allergy Association. Disease Summaries – Allergic Conjunctivitis.

Available at: www.worldallergy.org/public/allergic_diseases_center/conjunctivitis. Accessed December 15, 2014.

8. Power WJ, Tugal-Tutkun I, Foster CS. Long-term follow-up of patients with atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. Apr 1998;105(4):637-42.

9. Akpek EK, Dart JK, Watson S, et al. A randomized trial of topical cyclosporin 0.05% in topical steroid-resistant atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. Mar 2004;111(3):476-8.

10. Donnenfeld E, Pflugfelder SC. Topical ophthalmic cyclosporine: pharmacology and clinical uses. Surv Ophthalmol. May-Jun 2009;54(3):321-38.

11. Bischoff, G. Giant papillary conjunctivitis.Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2014 May;231(5):518-21

12. Allansmith MR, Korb DR, Greiner JV, et al. Giant papillary conjunctivitis in contact lens wearers. Am J Ophthalmol. 1977;83(5):697-708.

13. Forister JF, Forister EF, Yeung KK, et al. Prevalence of contact lens-related complications: UCLA contact lens study. Eye Contact Lens. Jul 2009;35(4):176-80.

14. Donshik PC. Giant papillary conjunctivitis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1994;92:687-744.

15. Abelson MB, Torkildsen G, Plumer A, et al. Giant Papillary Conjunctivitis; The dangers and treatment measures involved with “GPC.” RCCL. 2005;Nov;141(8):7.

16. Sforza C, Rango M, Galante D, et al. Spontaneous blinking in healthy persons: an optoelectronic study of eyelid motion. Ophthal Physiol Opt. 2008;28:345-53.

17. Katelaris, CH. Giant papillary conjunctivitis--a review. Acta Ophthalmol Scand Suppl. 1999;(228):17-20.

18. Elhers, WH, Donshik PC. Giant papillary conjunctivitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 Oct;8(5):445-9.

19. Zhong, X, Liu, H, Pu, A et al. M cells are involved in pathogenesis of human contact lens-associated giant papillary conjunctivitis. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2007 May-Jun;55(3):173-7.

20. Donshik PC, Porazinski AD. Giant papillary conjunctivitis in frequent replacement contact lens wearers: a retrospective study. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1999;97:205-16.

21. Fowler SA, Korb DR, Allansmith MR. Deposits on soft contact lenses of various water contents. CLAO J. 1985 Apr-Jun;11(2):124-7

22. Minarik L, Rapp J. Protein deposits on individual hydrophilic contact lenses: Effects of water and ionicity. CLAO J. 1989 Jul-Sep;15(3):185-8

23. Refojo MF, Leong FL. Microscopic determination of the penetration of proteins and polysaccharides into poly (hydroxyethylmethacrylate) and similar hydrogels. J Polym Sci Polymer Symp. 1979;66(1):227-37.

24. Minno GE, Eckel L, Groemminger S, et al. Quantitative analysis of protein deposits on hydrophilic soft contact lenses: I. Comparison to visual methods of analysis. II. Deposit variation among FDA lens materials groups. Optom Vis Sci. 1991 Nov;68(11):865-72.

25. Leahy C, Mandell R, Lin S. Initial in vivo tear protein deposition on individual hydrogel contact lenses. Optom Vis Sci. 1990 Jul;67(7):504-11.