|

A 59-year-old male presented to the clinic complaining of reduced vision in his right eye. He described his vision loss as generally painless (though he noted increasing photophobia) and occurring slowly over the last month. He stated, however, that his right eye is his poorer-sighted eye and said it was possible he had been experiencing reduced acuity over a longer period of time.

Obtain Ocular History

The patient had a corneal transplant on his right eye 20 years ago due to keratoconus and then on his left eye three years later. His postoperative course was unremarkable, though he noted that high levels of astigmatism limited the vision in his right eye. At the time he presented, the patient was not using any medicated drops but was wearing glasses to see.

Risky Business

Entrance testing showed the patient’s habitually corrected vision to be hand motion on the right eye without improvement on pinhole and 20/40 on the left, improving to 20/25 through pinhole. It was not possible to assess the patient’s pupillary response in his right eye due to a poor view of his iris, but his left eye showed brisk direct and consensual responses. Full and confrontation visual fields, which could only be grossly assessed on the right eye, were full to motion on the right and full to finger counting on the left. Due to anterior media opacity, an intraocular pressure (IOP) evaluation was postponed until after the slit lamp exam.

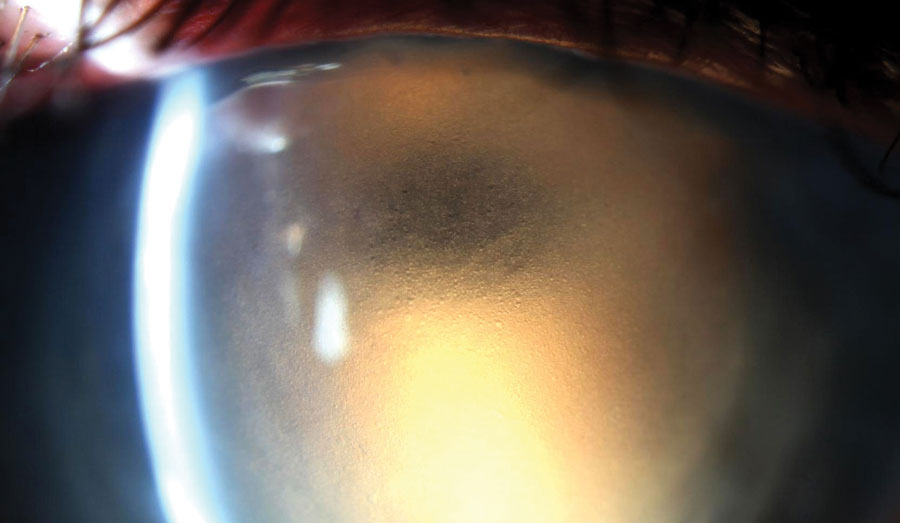

The slit lamp exam of the right eye showed normal lids. Injection, which was greatest nasally and interpalpebrally, was noted at 1+ to 2+ levels. The cornea showed a central penetrating keratoplasty (PK) with inferior vascularization to the graft-host junction of the transplant, though the vessels did not bridge onto the transplant. The graft was edematous with 3+ to 4+ epithelial and stromal edema, though the peripheral cornea remained clear.

Views of the deep cornea and anterior chamber (AC) were extremely poor, though no keratic precipitates (KPs) were seen, and the AC appeared to be quiet and absent of cells. The iris detail was poor, but with magnification of the slit lamp, the pupil was seen reacting to light. Examining the left eye showed normal anterior segment structures, with the exception of a PK. The interface had mild vascularization but was otherwise clear and compact. IOPs were 23mm Hg OD and 14mm Hg OS.

|

| We used retroillumination to highlight significant epithelial edema in this patient with a history of edematous PK. |

Determine the Problem

Though we could not rule out corneal graft rejection, we made a primary diagnosis of endothelial graft failure. To rule out rejection, the patient was instructed to use Pred Forte on his right eye every two hours for a week. A baseline pachymetry was gathered (1057µm OD and 712µm OS) to assess the patient’s treatment response. He was sent home and asked to return in a week.

Reassess at Follow-up

After a week, the patient’s exam results had not changed. Vision, IOP and pachymetry were stable. The slit lamp exam on the right eye showed no reduction in edema and still no visible KPs or intraocular injections. At this point, the diagnosis was confirmed, and we gave the patient the option of a repeat PK or a Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) behind the primary transplant. He elected to pursue the DMEK route. The patient underwent surgery uneventfully a month later. By the six-month postoperative visit, spectacle corrected visual acuity (VA) was limited to 20/60 minus, though the patient was pleased with the outcome.

Discussion

A patient presenting with significant corneal edema without apparent corneal or AC inflammation has a relatively straightforward differential diagnosis: viral endotheliitis, acute IOP spike (though we expect patients with a high enough IOP to generate pain, this is a trend and not a rule), hypoxia from contact lens use, corneal transplant rejection and native or transplanted endothelium decompensation. In this case, we can immediately rule out IOP and contact lens influences. While viral endotheliitis remains on the differential, in this patient with a history of PK but no history of viral eye disease, it is more appropriate to consider endothelial graft rejection or failure as the most likely suspects.

Note that all corneal transplants involving the endothelium—PK, DMEK and Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK)—fail eventually. Though some transplants last longer before failing, their average life expectancy is 10 to 20 years. Endothelial graft failure manifests as corneal edema, which is often mixed stromal edema (stromal pleats and Descemet’s membrane folds) and epithelial edema (microcystic corneal edema). It tends to occur slowly and without inflammation, though if bullae form, pain can develop.

On the other side of our differential is endothelial graft rejection. Though rejection is most likely to occur in the first year postoperatively, later cases of rejection do occur. Signs of this process are keratic precipitates on the graft and increasingly prominent corneal edema. Extracorneal inflammation may also be present but should be relatively mild. In some cases of rejection, the corneal edema may be too profound to visualize KPs. In this case, it can be impossible to clearly distinguish rejection from failure on exam.

In an eye with an endothelial graft and significant recent-onset corneal edema, use a high-dose steroid to differentiate failure from rejection. A few cases I thought for certain were cases of failed grafts showed improved edema and subsequent underlying KPs. In cases where edema clears, make a diagnosis of rejection. At this point, the patient should be very slowly tapered on the steroid (over six to 12 months) but should also be indefinitely maintained on a steroid dose greater than what was in effect when the rejection episode occurred. The longer a rejection episode goes on for, the more permanent the damage to the transplant and the higher the risk of failure due to endothelial cell density loss. In cases where there is no resolution of edema with steroid use, the patient likely has underlying graft failure and needs an endothelial re-transplant, either via a DSAEK, DMEK or repeat PK.

The current standard practice is to perform a lamellar transplant, as repeat PKs are more prone to complications and failure than are original PKs and secondary DMEKs and DSAEKs. There are cases where a repeat PK, however, is worth considering.

The patient noted that the vision in his right eye had never been as good as the vision in his left, owing to astigmatism. Though secondary DMEKs and DSAEKs have a more preferable safety profile than secondary PKs, do not expect these posterior lamellar surgeries to improve anterior corneal irregularities caused by an original PK. A repeat PK may be able to do just that. When we reviewed the course and recovery of all available options, however, the patient felt his acuity prior to graft failure was strong enough to function and knew he would be happy if he could get back to that level, so a DMEK was settled on.

When dealing with any new onset corneal edema in a transplant setting, it is important to arrive at the right differential and understand the diagnosis to effectively shape short- and long-term patient care.