|

A.T. is a 26-year-old Caucasian male who was seen for initial consultation for refractive surgery to address his moderate myopia (i.e., -4.25 OD and -3.75 OS). A comprehensive examination revealed no contraindications to the procedure, and the patient’s medical/ocular history was negative for allergies and family-related ophthalmic concerns. Following appropriate counseling and review, the patient elected to undergo a bilateral LASIK procedure for full distance correction. The procedure was completed without complication, and the patient was discharged on QID Zymaxid and Pred Forte.

The patient’s day one postoperative visit was unremarkable. His clinical examination revealed well-positioned flaps with full closure of the flap margins in both eyes, and no evidence of underlying flap complications. His visual acuity without correction was 20/20-1 OD and 20/20+1 OS. The patient was advised to maintain his current treatment regimen for one week, and follow up as scheduled.

On postoperative day two, the patient contacted the office and indicated a need to push his one-week appointment to a later date due to a personal commitment. However, on Saturday (i.e., four days postoperative), the patient contacted the service again to report that he developed a foreign body sensation in his left eye, accompanied by mild photophobia and some blur. After discussing the concerns with the patient, and due to an inability on the part of the patient to present to the office in the next 48 hours, I recommended increasing the Zymaxid to every two hours and decreasing the Pred Forte to twice daily until he could be seen.

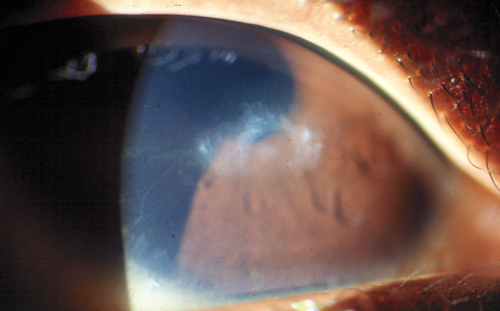

Sunday evening (i.e., five days postoperative), the patient contacted the service a third time to report that there had been an increase in symptomatology over the last 24 hours, and that he had returned to the area to be seen as soon as possible. Clinical examination on that date demonstrated a completely healed flap on the right side, with uncorrected vision at 20/15-1. The left eye, however, showed an area of sub-flap infiltrate measuring roughly 2mm to 2.5mm. This did not extend into the epithelial space, but did have a crystallized-like appearance around the margins. There were no cells in the anterior chamber. Minimal injection was present. Applanation pressures were 15mm Hg OD and 16mm Hg OS. There was no overlying epithelial staining, but there was a noticeable negative stain over the area, indicating a volume displacement under the cap with epithelial elevation. The patient’s vision was 20/50 uncorrected and 20/25 pinhole.

| |

Post-LASIK corneal ulcer. |

Given that the patient was almost six days postoperative, and the reason for the onset of this lesion was unclear, I decided to treat the lesion as infectious keratitis. The patient was placed on Q1hr therapy of vancomycin at 30mg/ml and Q1hr Zymaxid alternating at Q one-half hour. Steroids were discontinued. I discussed treatment options and recommended that, in addition to the topical therapy, cultures should be obtained from underneath the lifted flap. Additionally, I recommended rinsing with fortified vancomycin. This was done the following morning, and the patient returned for a one-day postoperative follow-up on the treatment, where he demonstrated improvement in his symptoms with an uncorrected acuity of 20/30.

The treatment was continued aggressively for 24 more hours, and then tapered. There was small improvement in the physical appearance of the lesion, but not complete extinction. So, four days into the treatment process, I added a steroid to the regimen; the patient subsequently demonstrated additional clinical improvement with no evidence of AC reaction, and injection significantly reduced. By the end of seven days, the patient had returned to 20/25 uncorrected acuity. At seven days out, further tapering of all topical therapy was initiated over a one-week period.

The Twist

At four days into the final taper of the medications, the patient contacted the office to indicate that the symptoms had returned. He was seen that afternoon for follow-up evaluation, which revealed that the lesion had increased with the reduction in topical treatment and was exhibiting a larger and denser atypical crystalline pattern than previously noted. Additionally, there was also a small (less than 1mm) corneal defect overlying the lesion. This was unlike the typical infiltrate that is seen with either leukocytes or neutrophils, based on whether viral or bacterial etiology was the source of the infectious process. I discontinued steroids and put the patient on full therapeutic regimen. Visual acuity dropped to 20/100 uncorrected (20/50+ pinhole) and the AC had a trace reaction.

After two days on the full therapeutic regimen, monitoring showed no notable improvement, and the cultures demonstrated no significant growth of either Gram-positive or Gram-negative organisms. The patient’s course was maintained, but because of the unusual appearance of the lesion, I decided to add an antiviral treatment (1,000mg Valtrex TID postoperative).

The lesion remained effectively unchanged, with a slow decrease in vision over a three-day period in the presence of full topical therapeutic intervention as previously mentioned. There was no satellite lesion development, nor did the basic presentation change materially, other than a slight increase in size of the underlying opacity beneath the flap, a slow decrease in vision and a notable increase in discomfort and photophobia.

On the fourth day, due to the progression of the lesion in the face of maximum therapeutic intervention, I decided to amputate the flap and re-culture the eye, which was accomplished the following day. The goal of the amputation was to allow better access of the antibiotics to the underlying lesion. The patient showed an initial improvement with this therapeutic intervention, but subsequently the lesion continued to slowly worsen, with vision declining to 20/150 pinhole and then approximately 20/60 at its worst.

The treatment was now approximately three weeks out from the initial procedure, and the patient still showed no notable improvement with multiple antibiotic systems and oral antiviral therapy. At this point, the material that was captured from the original culture came back from the laboratory with a positive identification of an acid-fast bacillus, which was identified subsequently as Mycobacterium chelonae. It was noted to be sensitive to amikacin, which was ordered at an appropriate concentration. Therapy was initiated Q1hr over and above the current treatment with the vancomycin and gatifloxacin until a response was obtained.

While M. chelonoe is a relatively rare organism in general cases of microbial keratitis following refractive surgery, it has been identified as a possible opportunistic organism. Standard postsurgical prophylaxis is directed toward the most common organisms and usually involves the use of a fourth-generation FQ as the antibiotic of choice. Of the unusual organisms that must be included in the differential diagnosis of postoperative microbial keratitis, MRSA is the most typical and thus prompted the use of the vancomycin empirically in this case.

On the new therapeutic regimen, the patient showed an initial response, but it was slow, so additional investigation was accomplished, and it was found that the organism was also susceptible to clarithromycin. A compounded version of this was obtained via overnight shipping and the patient was prescribed continued application of topical amikacin and clarithromycin, alternately. This led to a rapid improvement in symptoms, visual acuity and lesion size over a seven-day period. The patient continued on this therapy, and at the six-week postoperative visit was 20/30 with minimal-to-no photophobia and complete reduction of the hyperemia.

However, one small area of probable continued activity of the organism was noted, so therapy was continued for approximately eight additional weeks. Final visual acuity was 20/30+ uncorrected and 20/25 pinhole. Because of the crystallization of the lesion and due to the chronic state of the presentation, at some point in the future, if vision does not significantly improve, the patient should undergo a scraping of the material to provide a better refractive surface for improved visual performance.

Discussion

As seen in the above case, treating a postoperative refractive surgery infection can be both challenging and complex. In patients in which a 48- to 72-hour window takes place, treatment with fortified antibiotic systems like vancomycin, tobramycin and/or a topical fourth-generation fluoroquinolone fits the standard protocol; however, in patients for whom the organism is either nonresponsive to that protocol or in which onset of the lesion occurs at a later date, it is assumed that a more atypical organism is the driving force.

Note, it is in no way unusual for the patient to be treated as having a possible herpetic viral infection over the course of therapy, given the relatively atypical presentation that lesions like this create. Additionally, note that because of the extreme delay in the ability to culture organisms of this type, the clinician must demonstrate a level of patience for the treatment that can sometimes be quite trying.

Certain organisms such as atypical mycobacteria, nocardia and fungi are frequently treated empirically due to appearance, symptomatology or both. In the case of A.T., it was fortunate that the original cultures were obtained so they could be used to identify the organism. Overall, as LASIK is one of the most popular and successful procedures ever, it is important that in the case of a complication, clinicians do not forget the potential for an even more complex complication.