|

In a typical week at the Urgent Care service of an academic-based clinic, we may see cases as varied and interesting as bilateral disc edema, vitreous hemorrhage from diabetic retinopathy and bilateral granulomatous uveitis. But, by far, the number one reason a patient calls or walks into our clinics is the presence of a red eye. They have an infection and need antibiotics. However, a true bacterial conjunctivitis is rare in adults.

In fact, adenoviral conjunctivitis is the most common cause of red eye in the world.1 This may partly be due to the viruses’ resilient nature; they are resistant to disinfection and can spread via both direct (i.e., ocular and respiratory secretions) and indirect contact (i.e., inanimate surfaces such as doorknobs, tonometry probes, towels), which allows for them to be unwittingly and easily transmitted to potentially large groups of people during an early asymptomatic incubation period.2

What You’ll See

Adenovirus (ADV) can manifest as one of four clinical conditions: (1) epidemic keratoconjunctivitis, (2) acute hemorrhage conjunctivitis, (3) pharyngoconjunctival fever, and (4) nonspecific follicular conjunctivitis. Patients experience a viral prodromal phase followed by adenopathy, and sometimes fever, pharyngitis and upper respiratory infection.

| |

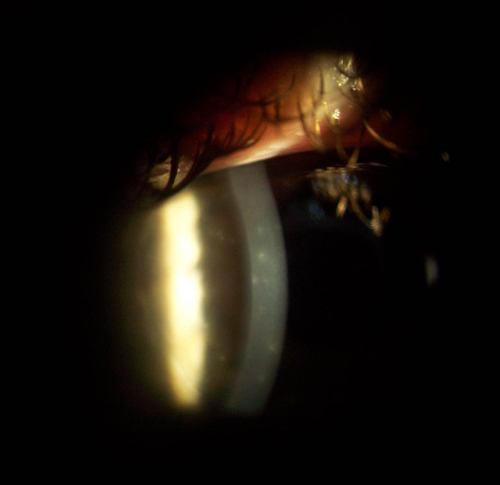

Subepithelial corneal infiltrates, which typically appear in the second week of infection, are virtually pathognomonic for adenoviral infection, particularly EKC. Photo: Jennifer Harthan, OD |

Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis (EKC), caused by adenoviruses 8, 19 and 37, is the most significant form of adenovirus because of the eventual involvement of the cornea and subsequent impact on vision.3-4 The presentation of EKC in its initial acute phase includes subjective complaints of unilateral tearing, redness, photophobia and eyelid edema, along with objective findings of conjunctival chemosis, follicular conjunctivitis and preauricular lymphadenopathy. The second eye usually becomes involved within days. This typically occurs about one week after exposure to the virus, and can last a few weeks.

The viral shedding can cause an intense inflammatory reaction in the conjunctiva that leads to pseudomembrane formation. The appearance of subepithelial corneal infiltrates, usually in the second week, signals the second phase of the infection and is virtually pathognomonic for adenovirus, most often EKC. These infiltrates can account for worsening symptoms and changes in vision, and can persist for anywhere from weeks to years.5 Severe complications may include chronic dry eye, conjunctival scarring and chronic epiphora. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) may be present with EKC and is indistinguishable from ADV.It’s clear that early detection of adenovirus is imperative, from both the perspective of providing the correct diagnosis and treatment for your individual patient as well as for the greater issue of public health by taking steps to curb the spread of infection. Rapid assay is available via a 10-minute in-office test (AdenoPlus, RPS) that the manufacturer says has 90% sensitivity and 96% specificity.6

For those not using the in-office assay to make the diagnosis, differentials include acute bacterial conjunctivitis, allergic conjunctivitis, episcleritis, angle closure glaucoma, blepharitis/dry eye, uveitis and infectious/inflammatory keratitis.

What to Do

Once the clinical picture and/or testing confirm the diagnosis, how do you treat EKC? While mild cases are usually self-limited and treatment is mostly supportive (chilled artificial tears, cool compresses, topical antihistamines), and education regarding proper hygiene and the contagious nature of the virus, moderate to severe cases involving subepithelial infiltrates and symptomatic pseudomembrane formation warrant intervention.

Sometimes, topical steroids are used for symptomatic relief, though there is always concern over potential side effects such as intraocular pressure rise and the possibility of rebound effect once the steroid is discontinued.7 Zirgan (ganciclovir gel 0.15%, Bausch + Lomb) has been shown to be effective against adenovirus in vitro and with significant inhibitory activity against HAdV3, 4, 8, 19a and 37, which induce epidemic keratoconjunctivitis.8-9 A small clinical trial of 18 patients found that the time frame of recovery was significantly reduced in patients treated with ganciclovir compared to preservative-free artificial tears (7.7 days vs. 18.5 days, respectively), with a lower incidence of SEI development.10 However, while a similar study found a faster and better response with ganciclovir, the results were not statistically significant.11

Many eye care providers advocate treatment with povidone-iodine, an antimicrobial that has been shown to be effective against adenovirus in vitro.12 Bear in mind, however, there are no controlled clinical studies to document its efficacy. Cyclosporine 1%, a steroid-sparing immunosuppressive, has been shown to be effective for the treatment of subepithelial infiltrates associated with EKC in patients resistant to the tapering of, or experiencing side effects from, corticosteroid drops, as has topical tacrolimus 0.03%, which has a similar mechanism of action but is decidedly more potent.13-14

Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis is a serious ocular infection for all concerned: the patient, their families, friends and colleagues, and the doctor entrusted to treat them. Early detection and patient education is mandatory to minimize contamination. Currently, there is no single accepted antiviral treatment—while there are options, none have been widely investigated with large clinical trials. Until such a time is reached, treat each red eye that comes into your office as a virus until proven otherwise, then treat the viral patient according to their signs and symptoms.

1. Samsburg R, Tauber S, Schirra F, et al. The RPS Adeno Detector for diagnosing adenoviral conjunctivitis. Ophthalmology 2006;113:1758-64.

2. Cheung D, Brenner J, Chan JTK. Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis—do outbreaks have to be epidemic? Eye 2003;17:539-87.

3. Jin X, Ishiko H, Na NT, et al. Molecular epidemiology of adenoviral conjunctivitis in Hanoi, Vietnam. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;142:1064-6.

4. Kinchington PR, Romanowski EG, Gorgon YJ. Prospects for adenoviral antivirals. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005;55:424-9.

5. Ford E, Nelson KE, Warren D. Epidemiology of epidemic keratoconjunctivitis. Epidemiol Rev 1987;9:244-61.

6. Sambursky R, Trattler W, Tauber S et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the AdenoPlus test for diagnosing adenoviral conjunctivitis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013 Jan;131(1):17-22.

7. Romanowski EG, Roba LA, Wiley L, et al. The effects of corticosteroids of adenoviral replication. Arch Ophthalmol 1996; 114: 581–5.

8. Trousdale MD, Goldschmidt PL, Nobrega R. Activity of ganciclovir against human adenovirus type-5 infection in cell culture and cotton rat eyes. Cornea 1994;13:435-9.

9. Huang J, Kadonosono K, Uchio E. Antiadenoviral effects of ganciclovir in types inducing keratoconjunctivitis by quantitative polymerase chain reaction methods. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014 Jan 30;8:315-20.

10. Tabbara K, Jarade E. Ganciclovir effects in adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis. 2001;ARVO abstract 3111 (suppl).

11. Yabiku ST, Yabiku MM, Bottós KM, et al. Ganciclovir 0.15% ophthalmic gel in the treatment of adenovirus keratoconjunctivitis]. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2011 Nov-Dec;74(6):417-21.

12. Monnerat N, Bossart W, Thiel MA. Povidone-iodine for treatment of adenoviral conjunctivitis: an in vitro study. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2006 May;223(5):349-52.

13. Jeng BH, Holsclaw DS. Cyclosporine A 1% eye drops for the treatment of subepithelial infiltrates after adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea 2011;30:958-61.

14. Levinger E, Trivizki O, Shcchar Y, et al. Topical 0.03% tacrolimus for subepithelial infiltrates secondary to adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol (2014) 252:811-16.