You can hardly read an optometric journal or attend a continuing education event today without hearing some mention of scleral contact lenses. As their popularity has continued to increase, so too have their clinical applications: once indicated only for unique cases, scleral lenses are now used in the treatment of ocular surface disease, post-surgical visual rehabilitation and correction of refractive error that is otherwise refractory to conventional approaches. This article will discuss several clinical cases that exemplify these lenses’ benefits in practice.

1. Filamentary Keratitis

A 26-year-old white male presented for follow-up one week after undergoing collagen crosslinking OD and a contact lens fitting OS. During the appointment, the patient stated his left eye was sensitive to light and had felt irritated over the last four days. His history was significant for advanced keratoconus OS, with no signs of the disease OD. Penetrating keratoplasty had been performed OS three months prior to the visit. The patient also had a history of corneal gas permeable (GP) lens wear but reported discontinuation, as he had found the lenses to be irritating. Additionally, he reported trying scleral lenses previously, but had discontinued them as well, having considered them to be cumbersome.

| |

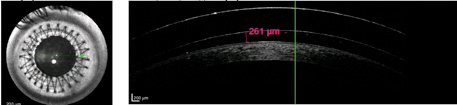

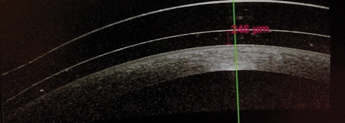

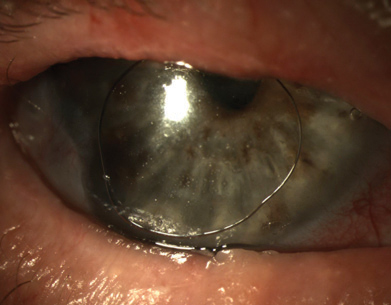

| Fig. 1. OCT of scleral contact lens at a follow-up visit. |

The patient’s uncorrected visual acuity was 20/25 OD and 20/200 OS, improving to 20/60 OS with pinhole. A biomicroscopy performed OS revealed the presence of a clear graft with intact running suture. Two filaments were also present outside the graft-host junction on the superior cornea. The patient was informed of contact lens options for his left eye, and elected to be fit with an intralimbal GP contact lens. He was also given preservative-free artificial tears to instill every half hour OS, in addition to an artificial tear ointment to apply prior to bed.

The patient was seen in clinic five more times over a two-and-a-half month period for a case of recurrent filamentary keratitis that prevented him from wearing contact lenses. Despite repeated removal of the filaments and adherence to the prescribed lubrication therapy, he could not achieve symptomatic relief. At this point, the patient said he regretted undergoing corneal transplant surgery, as his quality of life had severely decreased since the procedure.

A diagnostic scleral lens fitting was performed. The patient confirmed the contact lens offered relief of symptoms and a more permanent one was ordered.

| |

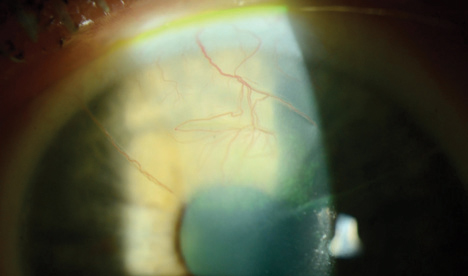

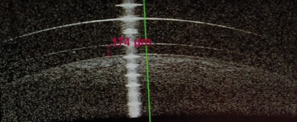

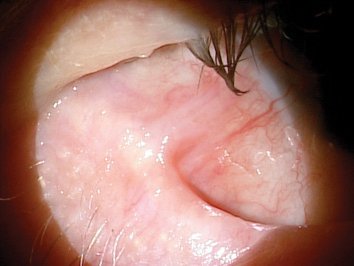

| Fig. 2. Biomicroscopic image of the superior neovascularization of the right eye. Of note is the neovascular vessel that occupies the potential space of the superior temporal radial RK slit. | |

| |

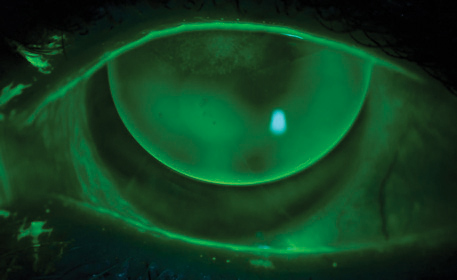

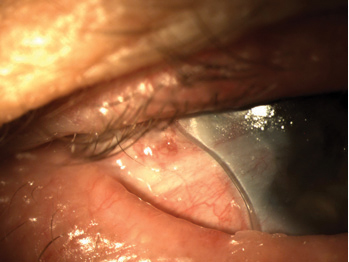

| Fig. 3. Biomicroscopic evaluation of habitual intralimbal lens OD. The lens bears on the superior cornea. Also visible is superficial punctate keratitis at the site of bearing. | |

| |

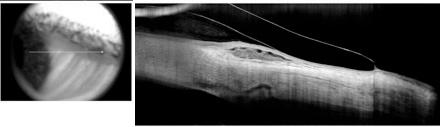

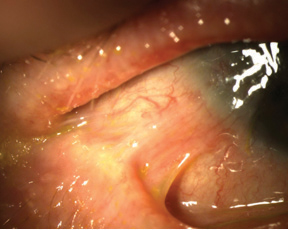

| Fig. 4. Peripheral anterior segment OCT image of the left eye. The demarcation of the clear cornea and opaque sclera is visible. This lens lands on the sclera outside of the limbus. |

Biomicroscopy of his left eye performed at the scleral lens dispensing visit revealed the presence of filaments at 9 o’clock, 11 o’clock and 12:30. The patient also complained of a consistent irritative feeling and photophobia; both improved upon insertion of the prescribed scleral lens. Vision with the lens was 20/25, improving to 20/20 with -0.50 overrefraction. At the one-week follow-up visit, the patient reported wearing the lens on average 14 hours a day (Figure 1). He added that his quality of life improved since adopting this lens modality. Biomicroscopy performed at that visit indicated no signs of staining or the presence of filaments. Observation of the patient lasted for another six weeks before the fit of the lens was finalized. One year later, the patient is wearing the scleral lens daily, with no recurrence of filamentary keratitis.

Generally, symptoms of filamentary keratitis range from mild ocular discomfort to extreme photophobia, tearing and pain, as was the case with this patient.1 The underlying cause of the filamentary keratitis is likely due to ocular surface dryness in relation to the penetrating keratoplasty; as such, frictional stress from blinking and reduced tear volume contribute to filament formation.2 In this example, the scleral contact lens formed a barrier between the lid and the ocular surface while creating a moisture chamber over the cornea. The patient had an almost immediate improvement of ocular comfort and quality of life after beginning to wear the lens, with eventual resolution of the filamentary keratitis.

2. Intralimbal Lenses

A 67-year-old white female with a history of radial keratotomy surgery performed in 1995 presented to the clinic with intralimbal gas permeable lenses fit at another location. Her entering visual acuity with the lenses was 20/50+2 OD and 20/50 OS. She also exhibited spectacle refraction of +6.00 -3.75x98 OD and +5.50 -4.75x77 OS that yielded 20/40- OD and OS. Biomicroscopy was remarkable for six radial slits with astigmatic keratometry inferiorly and superiorly (i.e., 4mm into the cornea), with neovascularization and four radial slits OD and pannus 4mm into the cornea, encroaching on the visual axis OS (Figure 2). The final diagnosis for this patient: corneal neovascularization secondary to superior bearing of an intralimbal lens (Figure 3).

At a subsequent visit, the patient was refit into an oblate-shaped, full scleral lens that landed outside the limbal stem cells. Visual acuity with overrefraction was 20/25-2 OD, 20/25 OS. OCT images taken upon initial fit demonstrated an optimal fitting relationship centrally and peripherally. Interestingly, in looking at the mid-peripheral zone of the lens, it lands outside the cornea and, presumably, past the limbal stem cells (Figure 4). At the final follow-up appointment, the patient reported increased comfort and overall happiness at the outcome. Visual acuity measurements were 20/25-2 OD, 20/25-1 OS, 20/25-1 OU. The patient was directed to return every six months to photo-document the neovascularization.

It is well known that mechanical irritation from contact lens wear can lead to limbal stem cell deficiency.3 This condition is characterized by corneal epithelial vortex keratopathy, neovascularization and loss of corneal clarity. In this case, there is no loss of corneal clarity, so it’s likely that the process of limbal stem cell deficiency was arrested by removal of the ill-fitting lens.

In general, with a presentation of corneal neovascularization, it is important to create a high Dk/t condition with the scleral lens. The best existing guidelines to achieve this dictate that, in order to provide adequate oxygen to the corneal surface, the lens should be manufactured with the highest Dk material available, and include a maximum center thickness of 250µm and maximum vault of 200µm.4 In this instance, the neovascularization was managed with topical corticosteroids and she was refit into a scleral lens where the above criteria was met.

3. Keratoconus with Front Toric

A 30-year-old white male presented for a contact lens fit complaining of ghosting. Additionally, he desired better vision and reported that previous attempts at contact lens wear had been unsuccessful. He was currently wearing glasses to achieve BCVA and presented with a history significant for keratoconus, for which had undergone collagen crosslinking OU three months prior. The patient’s visual acuity with glasses was 20/30 OD and 20/40 OS, which improved to 20/30 with pinhole. Lensometry indicated a current prescription of -1.75 +1.75 x 175 OD and -1.75 +2.00 x 10 OS.

| |

| Fig. 5. OCT of the left lens showing central vault of 246μm. | |

| |

| Fig. 6. OCT of the right lens showing central vault of 174μm. |

On external examination, the patient was noted to have small fissures. Biomicroscopy examination revealed partial Fleischer ring OU and early central corneal thinning, but no corneal scarring OU. The patient was fit into a hybrid contact lens design, but returned shortly to the clinic having ripped three lenses in the first 13 days of wear. He reported difficulty with insertion and removal despite repeated in-office training. He was subsequently refit into a mini-scleral lens during the second follow-up appointment, where he noted an immediate improvement in handling ability and a reduction in ghosting compared with the glasses. He added that his overall visual acuity remained similar, however, at 20/30 OD and 20/40 OS with the lenses in place. A spherocylindrical overrefraction of +0.50 +1.50 x 53 OD and -1.00 +2.00 x 155 OS improved his vision to 20/20 OD and 20/25 OS.

Topography over the mini-scleral lenses revealed approximately 1D of toricity in both eyes in the same axis of the corresponding overrefraction. Contact lens flexure was suspected to be the culprit for the majority of the residual astigmatism, so the lenses were reordered with increased center thickness. Unfortunately, the new lenses yielded a similar visual result—overrefraction and overtopography—leading the attending doctor to reorder them for the second time in a front toric prism ballast design to incorporate the residual cylinder correction found on overrefraction.

At the patient’s one-week follow up visit, visual acuity with the toric mini-scleral lenses was 20/20 OD and 20/20 OS (Figures 5 and 6). The patient reported seeing the best he had in years. Though some patients may report scleral contact lenses to be cumbersome due to intimidation from their size, reluctance to fill the bowl of the lens or dependence on a plunger for removal, this patient reported better ease of handling that allowed for more successful wear. Additionally, the scleral lens’s rotational and translational stability improved the patient’s blurry vision resulting from residual astigmatism.5

| |

| Fig. 7. Symblepharon appearing inferotemporally in the right eye. | |

| |

| Fig. 8. Full-scleral fit on the right eye with a notch inserted at the site of conjunctival elevation. | |

| |

| Fig. 9. Air injected into the post-lens reservoir when the notched lens rotated. | |

| |

| Fig. 10. The symblepharon remained unchanged three years after the initial presentation. |

Historically, corneal front toric gas permeable lenses have had problems with decentration and vision instability.6 These problems are easy to overcome in a scleral lens, however: in cases where residual astigmatism exists despite attempts to address flexure or other causes, adding a front toric correction to a scleral contact lens can result in high fitting success.

4. Ocular Cicatricial Pemphigoid

A 77-year-old white male with a history of ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP) symblepharon OU and severe dry eye OU was referred to the clinic by his corneal specialist for evaluation. His conjunctiva demonstrated significant symblepharon to within 1mm of the limbus OD (Figure 7). The patient was designated for a scleral lens fitting to treat the dry eye and modulate the progression of symblepharon. The first fitting included a notch at the site of conjunctival elevation (Figure 8); however, the notch rotated inconsistently and allowed air to enter the chamber, negating the attempt to treat the symblepharon (Figure 9). Subsequently, the lens diameter was reduced from 18.2mm to 15.0mm to try and “slot the gap” between the limbus and the symblepharon. This second attempt proved more successful and the patient was able to leave wearing the lenses comfortably.

Three years after the fitting, the patient returned to the clinic with a largely unchanged presentation, other than drying on the front surface of the lenses (Figure 10). Corrected visual acuity was 20/70 OD and 20/40+2 OS, while the appearance of the major site of symblepharon remained unchanged. The patient was subsequently refit into a duplicate lens with a new, wettable surface that improved visual acuity. Vision at dispensing was 20/30- OD, 20/25 OS and an OCT scan of the lenses demonstrated good alignment with just over 200µm of vault. The patient agreed to the proposed annual follow-up schedule to continually observe further changes.

The presence of OCP is correlated with severe dry eye, limbal stem cell deficiency and symblepharon.7 Literature reports have indicated contact lens use may be one method to prevent the progression of symblepharon; it’s possible that rigid scleral lenses can act as retainers to form a physical barrier to the immune-complex deposition believed to be responsible for the formation of symblepharon.8,9 In our experience, notching lenses can yield variable results: for example, in this case the notch was unstable and rotated. However, the lens used in this case was also fit before peripheral toricity became available. With the recent ability to stabilize lenses using peripheral toricity, notching may now be a more viable option to manage symblepharon.

5. Bilateral Penetrating Keratoplasty

A 27-year-old Hispanic male with a history of bilateral corneal transplants for keratoconus was referred to the clinic for a spectacle prescription. He reported spending the majority of the day with unaided vision, but wearing soft contact lenses when using the computer. These provided only minimal visual improvement. He did not own glasses and expressed a desire for better vision, as he was getting married in two months and wanted to pursue a career in law enforcement.

Entering visual acuity uncorrected was 20/200 OD and 20/80 OS with pinhole improvement to 20/30 OD and OS. Manifest refraction was OD -2.50 +6.00 x 180 20/25 and OS -6.25 +4.75 x 130 20/25. The patient was unable to tolerate the prescription when trial-framed in office; a discussion regarding contact lenses ensued.

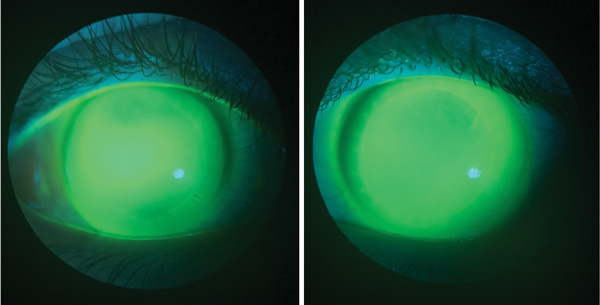

Based upon previous contact lens experience, scleral lenses were identified as the best option. On follow-up, vision with the scleral lenses was 20/20 OD and 20/20 OS. A broken running suture was noted on the left corneal transplant and subsequently removed; fit of the left lens was subsequently adjusted slightly to account for the change in corneal curvature. OCT over the lenses revealed minimal vault, so a new lens was ordered (Figure 11). Following fitting, the patient had been comfortably wearing his new contact lenses 12 to 14 hours a day for the past month. He commented that he “could not remember the last time his vision was this good,” and is currently waiting to hear back from law enforcement programs to which he had submitted his employment applications.

The visual correction provided by scleral lenses for irregular corneas is well documented. In the case of this patient, the improvement in visual acuity allowed him to pursue a career path that would otherwise have been closed to him.

It should be noted, however, that concerns exist regarding possible scleral lens-induced corneal hypoxia; in fact, there are still many unanswered questions regarding scleral lenses.4,10,11 When fitting corneal transplant patients with GP lenses, we recommend considering a corneal design before moving to a scleral lens approach. This patient’s history of previous contact lens failures played an important role in determining scleral lenses to be the lens of choice; a patient with different experiences may benefit from a different approach.

| |

| Fig. 11. Fluorescein evaluation of the right and left eye, respectively, at the initial follow-up visit. |

Scleral contact lenses are clearly a mainstay in our arsenal of tools when considering clinical management. Candidates spanning a broad range of complexity, from the most extreme cases to those with simple refractive error correction, benefit from scleral contact lenses. The cases presented illustrate only a small portion of the potential uses for sclerals—namely, ocular surface rehabilitation and improved ocular comfort and acuity. All of these, however, achieve the ultimate goal: enhancing the patient’s quality of life.

Dr. Malooley is an optometrist with Chicago Cornea Consultants and serves as adjunct assistant professor for the department of community based-education at the Illinois College of Optometry. She is also an advisory board member for the Gas Permeable Lens Institute.

Dr. Sonsino is a partner in a private practice in Nashville, TN. He is also a diplomate in the cornea and contact lens section of the AAO, chair-elect of the contact lens and cornea section of the AOA and an advisory board member for the GPLI. Dr. Sonsino is board-certificed by the ABO and consults for a number of vision companies.

1. Diller R, Sant S. A case report and review of filamentary keratitis. Optometry. 2005 Jan;76(1):30-6.

2. Tanioka H, Yokoi N, Komuro A, et al. Investigation of the corneal filament in filamentary keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009 Aug;50(8):3696-702.

3. Kim BY, Riaz KM, Bakhtiari P, et al. Medically reversible limbal stem cell disease: clinical features and management strategies. Ophthalmology. 2014 Oct;121(10):2053-8.

4. Michaud L, can der Worp E, Brazeau D, et al. Predicting estimates of oxygen transmissibility for scleral lenses. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2012 Dec;35:266–271.

5. Schornack MM. Scleral lenses: a literature review. Eye Contact Lens. Jan;41(1):3-1

6. Bennett E. Bending the Curve: How to Improve Toric Lens Success. Review of Cornea and Contact Lenses, 2013 Apr;j150(3):31-4.

7. Schornack MM, Baratz KH. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid: the role of scleral lenses in disease management. Cornea. 2009 Dec;28(10):1170-2.

8. Dunnebier EA, Kok JH. Treatment of an alkali burn-induced symblepharon with a Megasoft Bandage Lens. Cornea. 1993 Jan;12(1):8-9.

9. Proia AD, Foulks GN, Sanfilippo FP. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid with granular IgA and complement deposition. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985 Nov;103(11):1669-72.

10. Pullum KW, Stapleton FJ. Scleral lens induced corneal swelling: What is the effect of varying Dk and lens thickness? CLAO J. 1997;23:259–263.

11. Caroline P, Andre M. Using a Corneal Design to Manage Keratoconus. Contact Lens Spectrum. 2016 Jan;31(1):56.