Onset of bacterial keratitis secondary to improper contact lens wear is a serious condition that may lead to potential blindness, especially in the absence of adequate patient care and education.1 Because contact lens wear alters the state of the ocular surface, corneal homeostasis is also disrupted, compromising the natural defenses that predispose patients to bacterial infections and sight-threatening complications.2 As such, eye care practitioners play a vital role in providing the best treatment possible to alleviate corneal compromise and ensure successful visual outcomes.

The release of daily disposable contact lenses and high-Dk soft contact lens materials, as well as more effective antimicrobial medications, has meant that practitioners as a whole are seeing a decline in the severity of patients presenting with contact lens-related bacterial infections.3 However, though the level of infection has decreased, the number of infections has actually increased, primarily due to poor patient hygiene and noncompliance with care regimens and the overnight wear of contact lenses.4 Adopting more proactive measures may help prevent these potentially debilitating infections from occurring; thus, the prompt evaluation of contact lens-related infections is critical, as is the timely initiation of patient treatment.

Extended wear lenses manufactured with conventional hydrogel technology led many patients to develop corneal hypoxia. In response, silicone hydrogel lenses with high-Dk materials were created. These have since become the mainstay for patients requiring correction with soft lenses, though they interact no differently with the corneal epithelium than their predecessors did, especially in the case of overnight wear.5,6

Independent of their level of oxygen transmissibility, however, contact lenses in general provide a surface for microbial adhesion while also disrupting the normal tear exchange process for removal of bacteria and debris from the ocular surface.7,8 Constant mechanical rubbing of the lens and eyelid against the corneal epithelium further disrupts the turnover of epithelial cells, weakening the cornea’s defense system against bacteria looking for an opportunity to enter and infect the cornea.6

Weighing In

Risk factors that predispose patients to corneal infections secondary to contact lens use include immunosuppression, smoking, overnight lens wear, misuse/overwear of lenses, inadequate disinfection practices and contamination of lens solutions and/or lens storage cases. Patients with diabetes and other uncommon systemic illnesses should limit contact lens wear as certain conditions experienced by diabetes patients can delay wound healing, further exacerbate onset or progression of an infection and decrease treatment efficacy (Table 1).9 Patients of a younger age, male gender and/or higher socioeconomic status are also at an increased risk of an infection related to contact lens wear.10

Obtaining a detailed history is instrumental in ensuring proper management of bacterial infections. Patients should be asked about the initial onset of symptoms, type of contact lenses worn, wearing schedule, frequency of overnight wear, lens solution used and timing of lens case replacement. The presence of pain, redness, discharge or blurred vision can also provide clues as to the severity of the patient’s infection. A review of underlying medical problems, current systemic medications in use and any previous ocular history (including other infections, trauma, dry eye or ocular surgery) is also necessary to determine an appropriate care regimen.11

To avert a possible infection, practitioners should train patients on proper techniques for lens insertion, removal, cleaning, storage and disinfection. Furthermore, clinicians should also counsel lens wearers on effective hygiene practices, including handwashing, the use of approved contact lens solutions, frequent replacement of contact lens cases and avoidance of using tap water or saliva to lubricate their lenses.12 Additionally, instruct them to never reuse or “top off” the solution in their contact lens case. Rubbing the lens during cleaning also constitutes a vital step in the disinfection process. The FDA has outlined specific guidelines regarding proper patient handling and care of contact lenses.13 These are reproduced in a special patient education handout on page 21.

Visual aids and live demonstrations of proper contact lens handling methods can be effective as education tools. Counseling the patient regarding appropriate lens wear should occur at all follow-up examinations. Similarly, try to advise patients to contact a local eye care professional immediately should they experience any redness, pain, sensitivity or blurred vision associated with their contact lens wear.13

Practitioner treatment patterns during an active infection should focus on minimizing pain, restoring corneal integrity and minimizing scarring, with the ultimate goal of restoring visual function. Most patients are looking to alleviate their symptoms as quickly and effectively as possible using the most judicious treatment plans available; as such, it is the responsibility of the eye care practitioner to identify the infection’s severity, determine whether it is sterile or non-sterile, understand when to obtain a culture and realize when a prompt referral to a corneal specialist is necessary.14 Corneal devastation can take place rapidly if left unchecked, so prompt recognition and treatment of the problem is imperative to prevent visual loss.

| Table 1. Systemic Conditions that Contraindictate Contact Lens Wear |

| • Diabetes mellitus • Gonococcal infection with conjunctivitis • Debilitating illnesses, especially those that cause malnourishment or require respirator dependence • Vitamin A deficiency • Connective tissue diseases • Acoustic neuroma or a neurological surgery that causes damage to the 5th or 7th cranial nerves • Dermatological/mucous membrane disorders (e.g., Stevens-Johnson syndrome or ocular cicatricial pemphigoid) • Graft-versus-host disease • Immunocompromised status • Diphtheria • Atopic dermatitis/blepharoconjunctivitis • Chronic assisted ventilation |

Culture Shock

The majority of cases of bacterial keratitis reflect the normal flora of the ocular surface and largely result from gram-positive organisms like coagulase-negative Staphylococci, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus, as well as the gram-negative organisms Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Haemophilus influenzae.15 When contact lenses are introduced to the ocular surface, changes in the bacterial flora occur and may vary depending on patient age, sex, genetic makeup, climate and geographic location. P. aeruginosa is the most common pathogen present in contact lens-related infection cases due to its triggering of biofilm growth on both lenses and lens cases, and its ongoing acquired resistance to certain contact lens solutions and cleansers.16,17

In any case of a suspected bacterial infection, prompt identification of the offending organism causing the issue is an important step towards selecting the appropriate treatment. Since the introduction of fluoroquinolones, the need for culturing to identify the infection has dropped off significantly, with the majority of cases of contact lens-related bacterial keratitis managed without smears or cultures; however, antibiotic resistance is also increasing, with approximately 80% of current MRSA strains now resistant to fluoroquinolones.23 As such, obtaining a culture with appropriate culture media will help practitioners both detect resistant strains and also identify specific fungal, herpetic and Acanthamoeba infections.

|

|

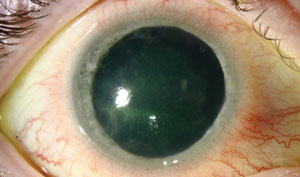

| Above, a patient presents with an Acanthamoeba infection. Below, the same patient seen one month later following a treatment regimen of chlorhexidine, voriconazole, PHMB and brolene QH; Vigamox (Alcon) and prednisolone QID; 200mg of oral fluconazole taken by mouth daily; and atropine applied once a day. Photos: Christine W. Sindt, OD |

Culturing is also warranted in cases when the patient’s cornea exhibits delayed healing, especially when a large, deep ulcer may be present within the visual axis. Culturing may be the best method to determine the most appropriate antibiotic necessary for treatment and also to help prevent antibiotic resistance. Other key reasons to perform a culture include the presence of vegetative material, corneal thinning, satellite lesions and/or recent care received in a hospital environment.24 Patients who present to the clinic in an immunocompromised state also require prompt culturing; in general, if a patient does not respond as expected to initial therapy, a practitioner should proceed with culturing immediately and also consider contacting an outside specialist.

First Responders

Regardless of the causative pathogen, first-line treatment for suspected bacterial infections should include broad-spectrum coverage against both gram-positive and gram-negative organisms.

Over the years, the choice of treatment for bacterial infections has changed with the introduction of fourth generation fluoroquinolones; with today’s array of topical antibiotic options, many practitioners reach for these medications with good reason. Fluoroquinolones provide excellent coverage for both gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens, and are readily available at generic prices with good ocular penetration and less risk of ocular toxicity.18 The newest fourth-generation fluoroquinolone, Besivance (besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension 0.6%, Bausch + Lomb), stays at high concentration in the tear film for a longer duration once dosed, and is available in a suspension instead of the more typical solution form.19

In cases in which a patient’s bacterial infection does not respond to fluoroquinolones, older antibiotics like bacitracin, tobramycin or gentamicin can be used instead. Additionally, consider the use of compounding fortified vancomycin or a combination of a fortified aminoglycoside plus fortified cephalosporine in cases in which methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is suspected, as fortified antibiotics offer more complete coverage of both gram-positive and gram-negative organisms. These generally require access to a compounding pharmacy, however.20,21

Corticosteroids, in contrast, are primarily reserved for treatment of sterile, noninfectious infiltrates that present in the peripheral cornea; indeed, corneal infiltrates that are the product of an inflammatory response respond well to both topical steroids and antibiotic combinations.22 These medications work via the inhibition of the inflammatory response to reduce corneal scarring but can also be damaging to the eye if applied too liberally, and so should only be used to treat centrally-located corneal infections that exhibit significant levels of staining.

When the scope of infection is beyond a certain level of comfort, the patient should be referred to a corneal specialist, where they will likely appreciate the ability to consult with an outside source who is well-equipped to both treat and manage their condition effectively.25 Patients who continue to experience a reduction in visual acuity at subsequent visits or an increase in pain and/or nonresolution of any corneal defects warrant prompt referral as well.

Annually scheduled eye examinations offer a great encounter in which to emphasize and review proper contact lens care and handling methods with patients. During these visits, practitioners are also able to monitor the patient’s ocular health and overall fit of their contact lenses in order to gauge their infection risk. Annual exams are also an appropriate time to switch solutions or upgrade the patient to a contact lens design and/or wear schedule that is more suitable for their individual lifestyle, which may increase compliance. Consider prescribing daily disposable lenses for young patients who have active lifestyles or poor hygiene, for example. Those patients who are involved in sports or who travel frequently may also enjoy the freedom offered by this modality, as without the need to worry about lens disinfection and/or case maintenance, the risk and severity of microbial keratitis is reduced.26

However, do not trust that all patients will dispose of their lenses following daily disposable wear and refrain from using their lenses overnight. Urge all patients to maintain a pair of spectacles in the event that an infection occurs, and suggest that lens prescriptions be updated annually. A fashionable pair is more likely to be worn in public, where it will give the patient’s eyes a rest, so consider investing in certain appealing designs. Lastly, above all patients considered unsuitable for contact lens wear should be advised against it completely. Practitioners should feel at liberty to deny contact lenses in cases where a patient seems to be unfit—either physically or psychologically—even at the cost of losing the patient from the practice’s population.

| Overnight Sensation | |

|  |

| The patient presented with a 2mm inferior corneal defect. | |

| A 27-year-old male presented to the clinic with an acute red eye following wear of his soft contact lenses overnight. His initial symptoms consisted of a red eye with intense pain, photophobia and blurred vision. The patient’s visual acuity was reduced five lines and a slit lamp examination revealed an excavated corneal defect 2mm in diameter located at six o’clock (see photos at right) on the right eye. The anterior chamber presented with trace cells, minimal flare and no hypopyon. The patient was directed to begin around-the-clock moxifloxacin, one drop administered every hour, and was also advised to discontinue wear of his contact lenses immediately. During the next day follow-up, an improvement of two lines in the patient’s visual acuity was noted, while the patient’s level of comfort had improved considerably with a reduction in both pain and photophobia. Daily follow-up examinations continued to demonstrate remarkable improvement in physical signs with a healing corneal defect and quiet anterior chamber. The antibiotic was tapered on day three to every other hour and then to QID by day five. At the 10-day follow-up appointment, the patient presented with an intact cornea and scarring in place of the presumed infectious ulcer. Visual acuity restored and the patient resumed contact lens wear in a daily disposable modality, with the recommendation that he limit lens wear and discontinue overnight wear. Refractive surgery options were also reviewed | |

With 41 million contact lens wearers in the United States today, practitioners need to remain ahead of possible infections by keeping patients aware of potential contact lens-related complications and continually reiterating best practices for contact lens wear and care at each visit.27 Until a lens is designed that incorporates an optimum balance of surface wettability, biocompatibility and resistance to micro-organisms, practitioners and patients alike must strive to maintain a proper contact lens wear regimen.

1. Barlett J, Karpecki P, Melton R, Thomas R. New paradigms in the understanding and management of keratitis. Review of Optometry. 2011 Nov; 1-16.

2. Fleiszig SM, Glenn A. Fry award lecture 2005. The pathogenesis of contact lens-related keratitis. Optom Vis Sci. 2006 Dec; 8:866-873.

3. Cheng K, Leung S, Hoekman H, et al. Incidence of contact-lens-associated microbial keratitis and its related morbidity. Lancet, 1999. 354(9174):181-5.

4. Weissman B, Mondino BJ. Why daily wear is still better than extended wear. Eye Contact Lens. 2003 Jan;29:145-146.

5. Bruce AS, Brennan NA. Corneal pathophysiology with contact lens wear. Surv Ophthalmol. 1990 July;35(1):25-58.

6. Stapleton F, Stretton S, Papas E, et al. Silicone hydrogel contact lenses and the ocular surface. Ocul Surf. 2006 Jan;4(1):24–43.

7. Lavker RM, Sun TT. Epithelial stem cells: the eye provides a vision. Eye (Lond). 2003 Nov; 17(8):937–942.

8. Paugh J, Stapleton F, Keay L, Ho A. Tear exchange under hydrogel lenses: methodological considerations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001 Nov; 42(10): 2813-2820.

9. AAO Cornea/External Disease Panel, Bacterial Keratitis. Available at www.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/bacterial-keratitis-ppp--2013. Accessed June 20, 2016.

10. Edwards K, Keay L, Naduvilath T, et al. Characteristics of and risk factors for contact lens-related microbial keratitis in a tertiary referral hospital. Eye. 2007 Aug;23:153-160.

11. Wilhemus KR. Review of clinical experience with microbial keratitis associated with contact lenses. CLAO. 1987 July; 13(4):211-214.

12. Centers for Disease Control. Healthy Contact Lens Wear and Care. Available at www.cdc.gov/contactlenses. Accessed June 20, 2016.

13. US Food and Drug Administration. Contact Lens Solutions and Products. Available at www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm048893.htm. Accessed June 20, 2016.

14. Silbert JA. Corneal infiltrative complications associated with contact lens wear. Rev Optom 2004 Apr;141(4):95-102.

15. Wozniak R, Aquavella J. Considering keratitis: critical questions in disease management. RCCL. 2015 Oct; 28-31.

16. McLaughlin-Borlace L, Stapleton F, Matheson M, Dart JKG. Bacterial biofilm on contact lenses and lens storage cases in wearers with microbial keratitis. J Appl Microbiol. 1998 May;84(5):827–838.

17. Lakkis C, Fleiszig SMJ. Resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates to hydrogel contact lens disinfection correlates with cytotoxic activity. J Clin Microbiol. 2001 Apr;39:1477–1486.

18. Baum JL. Initial therapy of suspected microbial corneal ulcers. I. Broad antibiotic therapy based on prevalence of organisms. Surv Ophthalmol. 1979 Sep-Oct;24(2):97–105.

19. Haas W, Pillar CM, Zurenko GE, et al. Besifloxacin, a novel fluoroquinolone, has broad-spectrum in vitro activity against aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009 Aug;53(8): 3552-3560.

20. Lin CP, Boehnke M. Effect of fortified antibiotic solutions on corneal epithelial wound healing. Cornea 2000 Mar;19(2):204-6.

21. Bowe BE, Snyder JW, Eiferman RA. An in vitro study of the potency and stability of fortified ophthalmic antibiotic preparations. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991 Jun;111(6):686–689.

22. Srinivasa M, et al. Corticosteroids for bacterial keratitis: the steroids for corneal ulcers trial (SCUT). Arch Ophthalmol. 2012 Feb;130(2):143-150.

23. McLeod SD, Kolahdouz-Isfahani A, Rosta-mian K, et al. The role of smears, cultures, and antibiotic sensitivity testing in the management of suspected infectious keratitis. Ophthalmology. 1996 Jan;103(1):23-8.

24. Rodman RC, Spisak S, Sugar A, et al. The utility of culturing corneal ulcers in a tertiary referral center versus a general ophthalmology clinic. Ophthalmology. 1997 Nov;104: 1897-1901.

25. Kent C. Winning the battle against corneal ulcers. Rev Ophthalmol. 2013;16(9):20-31.

26. Dumbleton KA, Richter D, Woods CA, et al. A multi-country assessment of compliance with daily disposable contact lens wear. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2013 Dec;36:304-312.

27. Nichols J. Annual Contact Lenses Report 2015. Contact Lens Spectrum. 2016 Jan;31:18-23.