|

As important as visual acuity surely is to contact lens wearers, it’s fair to say that comfort matters even more. Roughly 50% of contact lens wearers reported lens comfort issues when questioned during a 2002 study, so it’s not surprising that discomfort is considered the number one reason for the discontinuation of lens wear.1,2 For this reason, we are constantly striving to keep the ocular surface healthy and conducive to comfortable contact lens wear.

Contact lens-related dryness is a fairly common phenomenon characterized by the appearance of dryness symptoms only during contact lens wear. However, there are times when an underlying ocular surface condition, such as dry eye disease, can be the root of the problem causing the lens intolerance. In these cases, it’s fair to wonder how an already dysfunctional tear film could tolerate the presence of a lens without even further disruption. In fact, there are some instances in which dry eye can be treated using contact lenses.

Choosing a Lens

When the ocular surface is compromised, much of the discomfort our patients feel derives from mechanical trauma as the eyelid passes over the weakened corneal surface. As such, there are benefits to placing a contact lens upon the ocular surface: it immediately decreases pain sensations because it acts as a shield over the irritated cornea, allowing the epithelium to heal without the constant interference of the eyelid sweeping over the surface.

However, bandage contact lenses should be used with caution. If a patient’s cornea is compromised due to an infectious etiology, placing a contact lens over an ulcerated cornea could harbor the offending organism, making the condition significantly worse.

| |

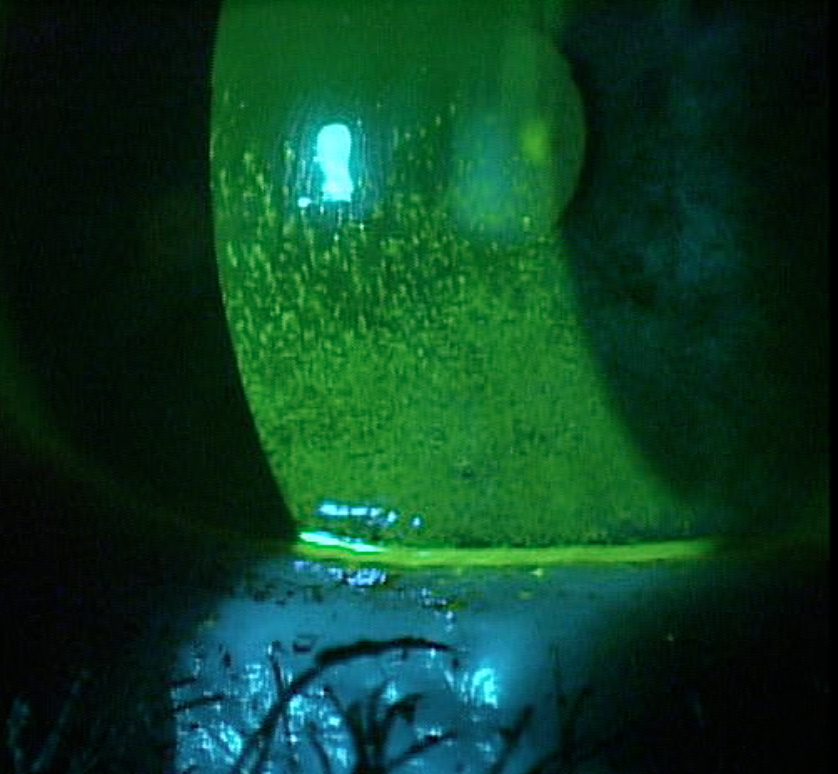

| Fig 1. Significant corneal staining in a patient with Sjögren’s, fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis. | |

| |

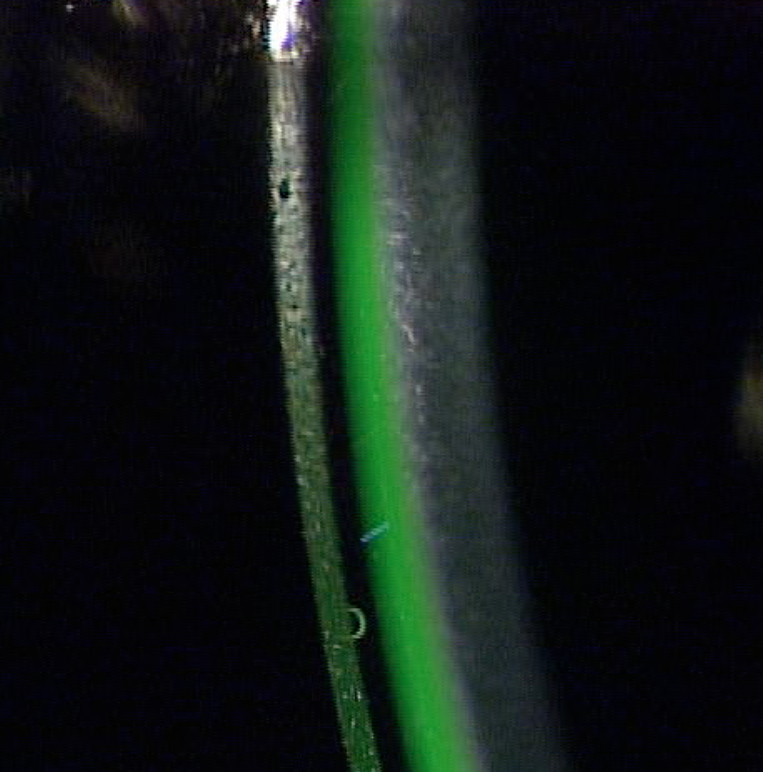

| Fig 2. A scleral lens was designed to address her corneal compromise. | |

| |

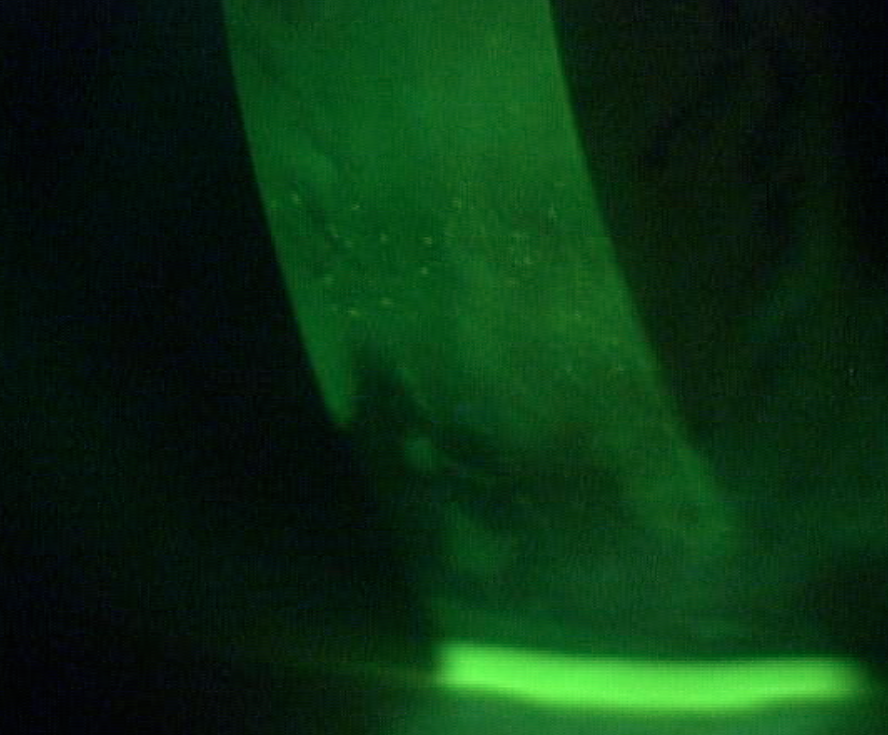

| Fig 3. After one week of wear, only trace amounts of staining remain. |

While a number of lens types can be used as bandage lenses, silicone hydrogel lenses are a particularly common choice as they allow significantly more oxygen to reach the cornea, mitigating any hypoxic stress that could compromise corneal physiology. However, while these lenses are successful in blocking the lid’s mechanical irritation of the cornea, they often do little to encourage healing in a patient with corneal compromise, and so must be combined with additional treatment methods.

An intervention gaining favor in recent years is to stimulate wound healing with amniotic tissue. In one method, a plastic ring anchors a cryopreserved amniotic membrane along the conjunctiva and holds the membrane against the cornea and conjunctiva. Another uses a dry amniotic membrane that is placed directly on the cornea. A bandage contact lens is then typically placed on the eye, which keeps the amniotic membrane in place against the compromised cornea.

Scleral lenses also exist as an alternative contact lens option for those exhibiting chronic dry eye with severe ocular surface damage. Typically, each lens is filled with non-preserved saline before being inserted onto the eye, where it provides a bath of continuous moisture to the compromised cornea. Additionally, the rigid lens material creates a smooth refracting surface, which is often absent in a severely compromised cornea. With an appropriate prescription, the lens may provide the patient with visual correction while simultaneously rehabilitating the surface.

Fitting scleral lenses for a severely compromised cornea as a result of dry eye relies on the same principles used to fit these lenses for any other patient. There are three major goals: (1) achieve a central corneal clearance between 100µm and 300µm, (2) keep the corneal region free of any contact with the lens, and (3) design a scleral landing free of impingement or compression—that is, one that conforms to the curvature of the conjunctiva and underlying sclera.

Considering these factors when dealing with your severe dry eye patients will not only help keep them in lenses but will also help you rehabilitate and protect some of your most severe cases of corneal compromise.

Alternative Therapies

Several other treatment options exist that can be attempted prior to scleral lenses. Lacrisert, a hydroxypropyl cellulose ocular insert, can be placed in the inferior cul-de-sac, where it slowly dissolves over 24 hours, stabilizing the tear film and increasing tear break-up time. Another option, punctal occlusion, retains tears on the ocular surface and could be considered for patients whose ocular surface inflammation has been controlled.

Autologous serum can also be used if the ocular surface is severely compromised. To create an autologous serum, the patient’s blood is drawn and the serum is separated through centrifuge. The serum is then usually diffused with an artificial tear and placed in vials for patient use.

Case in Point

A 57-year-old female came in for a routine eye exam. She has Sjögren’s syndrome, fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis. She is currently wearing silicone hydrogel contact lenses as bandage lenses because of severe corneal compromise resulting from Sjögren’s syndrome, as well as the need for corrective lenses. The lens parameters were: OD +5.00/8.6/14.0, OS +2.00/8.6/14.0. She was using a monovision approach, with the left eye adjusted for best near focus. She reported trying various soft lenses in the past, including daily disposables, but said her current lens modality offered the best handling, vision, comfort and resistance to deposits.

Even though these soft lenses functioned well for her, she nevertheless complained about fluctuating vision and uncomfortable lens wear. Symptomatic ocular surface dryness while wearing contact lenses was significantly better than how her eyes felt in the absence of lenses. To help control her symptoms, she was using Systane Ultra 1-2gtt BID-QID OU over her contact lenses. Upon physical examination, her corneas were remarkable for significant corneal staining of the inferior half of the cornea (Figure 1).

The patient was fit with scleral lenses with appropriate central and limbal clearance (Figure 2), and a suitable scleral landing zone. She was instructed on proper lens insertion, removal and care. The lenses were dispensed and she was seen one week later for follow-up. At that time, she reported significantly improved comfort and vision with the scleral lenses. She was able to wear the lenses for the whole day and only sporadically had to use artificial tears.

Upon lens removal, there was just a trace amount of corneal staining present (Figure 3). The patient will continue to wear these lenses for the foreseeable future.

Because dry eye can arise from many different potential causes, the best treatment method can vary. This example demonstrates the appropriate use of scleral lenses for severe ocular surface disease, but other causes may be best managed with soft lenses, or no lens at all.

1. Young G, Veys J, Pritchard N, Coleman S. A multi-centre study of lapsed contact lens wearers. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2002 Nov;22(6):516-27.

2. The Definition and Classification of Dry Eye Disease: Report of the Research Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocular Surf. 2007 Apr;5(2):179-93.