|

Microbial keratitis (MK), including bacterial, fungal and protozoan forms, is a common clinical entity, with an estimated 30,000 to 70,000 cases each year in the United States.1,2 Though medical management is often successful, these pathologies continue to be a significant source of corneal vision loss, emergent keratoplasty (in cases of impending infectious perforation), non-emergent keratoplasty (to treat resultant scars) and, rarely, enucleation or evisceration.

Infectious corneal ulcers don’t always make their intentions known on presentation and their care, no matter how insignificant the original ulcer, needs to be carefully managed to ensure the best outcome.

The first, often trivialized, step in managing an infectious corneal ulcer is defining the lesion as microbial in nature. This is a question everyone struggles with on occasion. Many cases of MK will be easily discernible from other pathologies, but not all of them. Everything from corneal deposits and inflammation to edema may occasionally masquerade as a possible infection.

Let’s take a closer look at the various management aspects of MK, beginning with differentiation. Subsequent columns will walk you through when to culture, common treatment strategies, the role of emerging resistance in treatment and advanced treatment options.

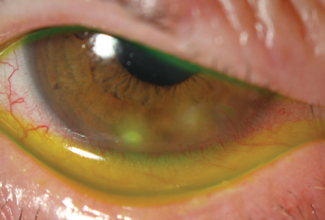

|

| Sterile marginal keratitis is differentiated easily from microbial keratitis based on location. This patient had no specific risk factors for microbial keratitis. |

The Differentials

As the name implies, an infectious corneal ulcer almost universally requires an epithelial ulceration. Exceptions to this rule are rare and include early-stage Acanthamoeba epithelial keratitis (AK) and some fungal infections that may be so indolent the epithelium heals over them. But for the most part, microbial pathogens require a breach in the epithelium to adhere to and colonize the cornea. Because the resultant inflammation will prevent migration of the epithelium over the top—stromal inflammation impedes epithelialization—MK should have an epithelial defect as large as or larger than the infiltrate. Of course, most epithelial defects are not infectious in origin, and for the cause of a defect to be MK, an infiltrate must be present at its base.

MK infiltrates are generally grey, white or yellow, quite dense, typically (though not always) round or oval and well circumscribed (unlike zones of corneal edema, which have more nebulous margins).

Other non-infectious sources of corneal infiltration include hypersensitivity reactions, contact lens keratitides and stromal viral keratitis. These may result in an infiltrated stroma, though they are often multifocal, small in size or may not have an epithelial ulceration. To differentiate, the size of the lesion is key, as those with diameters 2mm or greater are typically infectious. Extracorneal signs can be helpful, with mucous discharge and heavy anterior chamber reaction being more common in microbial cases compared with serous discharge and little to no anterior chamber reaction in non-microbial cases.

Location should also play a prominent role in your differential. Due to differing zones of corneal immunity (with the peripheral cornea being immediately adjacent to the immunologically active limbal zone and the central and paracentral cornea being immune privileged) the cornea will respond variably depending on the location of the insult. The peripheral cornea is more likely to contain MK in its cradle, but also more likely to generate hypersensitivity reactions. The central cornea is less likely to generate hypersensitivity reactions, but isolated lesions of this zone are more likely to be infectious (including viral etiology) rather than sterile. While not all lesions of the periphery are sterile and not all central infiltrates are infectious, lesion location should weigh into your final differential.

The final element in differentiating the likelihood of MK from other forms of keratitis is a careful patient history. This is crucial to uncovering a historic risk that supports the development of MK. Roughly 90% of MK cases have a historic risk factor that compromised the cornea, allowing adherence of the microbe and subsequent colonization.3

For those without a risk factor, other possibilities such as viral keratitis should be considered more closely. Further, the specific risk factor should also influence your diagnosis. Patients with contact lens use can have gram-positive, fungal or protozoan etiologies, though gram-negative species become relatively more common in this setting. Patients with chronic ocular surface disease or ophthalmic surgery as a risk factor likely have a normal flora etiology, often Staphylococcal. Finally, when patients present with a history of environmental trauma, the index of suspicion should tilt dramatically towards atypical bacteria and fungi.

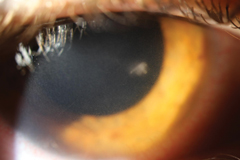

|

| This infiltrate is roughly the same size as those in the first image but, based on location, is most likely microbial in nature. While no definitive rule regarding location exists, a central ulcerated infiltrate larger than a pinhead has a high likelihood for being infectious in nature. When paired with other risk factors, such as contact lens use, suspicion goes up even higher. |

Splitting Hairs

Once you know you are dealing with MK, you should further differentiate the offending agent: gram-positive, gram-negative, atypical bacteria, fungus or Acanthamoeba. This will have dramatic bearing on whether you culture or not, and what initial therapy you select.

Though a definitive diagnosis is clinically impossible, given classic features are sometimes absent and individual immune differences create varying clinical appearances even among ulcers of the same species of bug, general trends can help you hone in on the right culprit and appropriate treatment. Gram-negative ulcers tend to have infiltrates with greater suppuration (more mucous-like in appearance) and may be less uniform in their density. When teaching, I tend to describe their density in culinary terms (chowder-like or like soft serve ice cream—disgusting, I know, but generally accurate). These ulcers also tend to worsen more rapidly, whereas gram-positive ulcers tend to progress more slowly (except Streptococcus pneumoniae).

Gram-positive ulcers are often somewhat dry in appearance, tend to have less surrounding edema, are generally well-defined and uniform and will frequently display a prominent anterior chamber reaction.

Fungal ulcers are well known for their potential to form feathery infiltrates, be leathery in appearance, grow satellite lesions and, depending on the specific fungal etiology, generate a pigmented infiltrate. While these are all helpful indicators, one review found that more than 50% of fungal ulcers initially don’t have any findings suggestive of a fungal etiology—a feature that leads to frequent initial misdiagnosis.4

AK in its early stage is an exception to the general rules of clinical appearance of corneal infection, as there is no well-demarcated infiltrate. Instead, early AK is characterized by a localized cystic epitheliopathy, which may be lightly infiltrated, but looks vastly different from its bacterial and fungal counterparts and is frequently confused with herpetic disease.5 Perineuritis, which may be subtle or obvious, can further clue the clinician into an amoebic etiology. In its late stages, AK is characterized by a ring ulcer. This infiltrate has greatest density around its edges, is generally well centered around the corneal apex and is ulcerated (distinguishing it from the Wessely immune ring processes seen with viral eye disease and, occasionally, with gram-negative bacteria).

Once you know an infiltrate is infectious and the specific etiology you are likely dealing with, you are ready to use these diagnostic considerations to inform your treatment decisions—giving your patient the best possible outcome.

1. Pepose JS, Wilhelmus KR. Divergent approaches to the management of corneal ulcers. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;114(5):630-2. |