|  |

As eye care practitioners, we fit all types of patients for contact lenses. They can range from standard spherical prescriptions to the most complex corneas—and the road to successful lens wear is not always smooth.

Currently, the main reasons a patient will discontinue lens wear are discomfort and dryness.1 Over the years, manufacturers have made much headway in modalities, designs and surface chemistry to make contact lenses more comfortable. So, why do so many lens wearers become uncomfortable in their lenses?

The ocular surface is a major contributor to contact lens comfort. A healthy ocular surface gives our patients the best chance for successful lens wear, and a compromised ocular surface can play a big part in a patient’s unsuccessful lens wear. Also, as contact lens wearers age, they generally complain of contact lens discomfort more often.2 To improve contact lens comfort, we must find strategies to optimize the ocular surface; based on recent reports, the eyelids might be a good place to start looking.

|

|

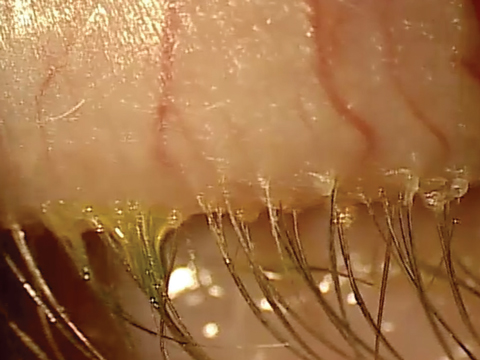

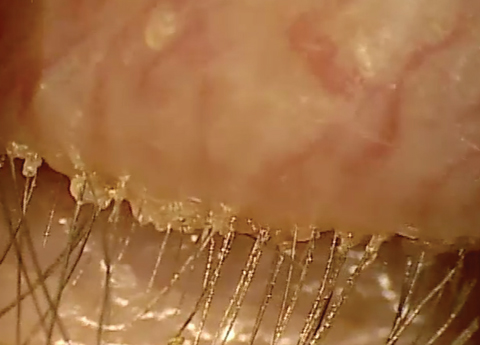

| At top, mild signs of blepharitis with some debris noted at the base of lashes. At bottom, severe blepharitis with more debris noted at the base of the lashes. |

A Deeper Dive

Studies indicate that the bacterial load on the lid margins is normally present in low concentrations, often referred to as the normal flora.3 The two most common bacteria that can inhabit the eyelids are Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus. The normal flora lives in a biofilm that allows adequate amounts of bacteria to live in harmony with the host. When imbalances in the local environment occur, over-colonization can lead to greater concentrations of microbes. Bacteria can sense the increased concentration, and when it achieves a certain quorum, it activates dormant genes. These are responsible for producing proteins that cause a wide array of virulence factors and, ultimately, inflammation in the tissue. This occurs over decades and is believed to be the underlying cause for many of the signs and symptoms we see in our dry eye patients.

The report’s authors propose a new term for this, dry eye blepharitis syndrome (DEBS), and four stages in which it manifests from the over-colonization of bacteria on the lid margin:

Stage 1 involves the lash follicles. There is a potential space between the lash and the surrounding follicle that allows the biofilm to extend. Overpopulation of this region initially creates a subtle edematous follicular tissue that extends around the lash. Scurf or debris at the base of the lashes is simply the overpopulation of bacteria in the follicle. Take into consideration the natural growth of the lash and you can understand why at times this scurf is seen clinically at different levels along various lashes. When this occurs over decades, we may not see as much scurf at the lash margin, possibly because the lash bulb may be so badly damaged that the lash is growing at a significantly slower rate, if at all. Without normal growth, the lash is unable to push bacteria out of the lash margin. All of this can also lead to lash loss.3

Stage 2 includes the meibomian glands as well as the lash follicles. In a normal state, the meibum is constantly flowing out of the narrow ductule, impeding the bacteria’s ability to overpopulate the gland. As the biofilm extends toward the meibomian glands, it can slowly begin lining the orifice and entering the glands. Over time, this creates distension and affects the glands’ ability to produce secretions.3

Automated heat and expression procedures such as LipiFlow (Tear Science) can remove the contents of the glands and, ultimately, the source of the virulence factors and inflammation within the gland.3

Stage 3 involves the accessory glands of Krause and Wolfring. These glands produce basal levels of aqueous for the ocular surface, and their anatomical location makes them less accessible to the biofilm on the surface of the eye. This also helps explain why we often see the meibomian glands as greater contributors to dry eye in non-Sjögren’s forms of dry eye.3

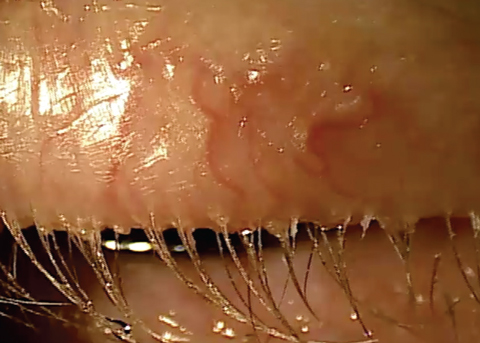

Stage 4 describes the structural integrity of the lid margin becoming compromised because of the prolonged exposure to inflammation. Lid laxity, entropion, ectropion, madarosis and trichiasis may all be manifestations of extended inflammation.3

|

| Chronic blepharitis showing eyelash loss and misdirected lashes. |

Putting It All together

DEBS can help explain why the tear film quality of some patients may constantly degrade over time. It can also give us a new appreciation for the bacterial biofilm and what can happen when bacteria densities increase above normal ranges, along with inflammation. More importantly, from a clinical perspective it provides us guidance on what we can do to prevent these long-term chronic changes from occurring.

In theory, reducing the bacterial bioload on the lid margin should improve signs and symptoms of dry eye. Some studies have shown improvement in dry eye signs and symptoms after the use of microblepharon exfoliation.4,5

Loaded Lids

Recently, researchers in Australia investigated the influence of the eyelids on contact lens comfort in 30 patients and randomly split them up into groups treated with either microblepharon exfoliation treatment using BlephEx (Rysurg) or a lid hygiene product.6

Results show that the bacterial load on the eyelids was significantly greater in patients who were symptomatic for contact lens discomfort than those who were comfortable in their contact lenses.6 After mircoblepharon exfoliation treatment, the bacterial load on the eyelids was significantly reduced.

Additional eyelid findings, including gland orifice capping and quality of meibum secreted, were also improved after this treatment. In one compelling statistic, of the 17 patients who were symptomatic lens wearers prior to treatment, 10—or 59%—were asymptomatic after microblepharon exfoliation treatment.

In the lid hygiene group, the lid margin microbial load was also measurably reduced, but there was no improvement in the additional eyelid findings that improved in the BlephEx group.6

Because the eyelids and the bacterial bioload they carry may affect the health of the ocular surface, understanding them could help us uncover reasons for contact lens discomfort. By being cognizant of the effects of the lid margin and incorporating strategies to improve its health, we can enhance lens wear for our patients and ultimately keep more of them wearing lenses.

1. Dumbleton K, Woods CA, Jones LW, Fonn D. The impact of contemporary contact lenses on contact lens discontinuation. Eye Contact Lens. 2013;39(1):93-9. |