|

The previous 2017 editions of this column have focused on the wide variety of presentations of herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis. While it’s almost time to turn the page on HSV keratitis, no discussion would be complete without outlining treatment considerations.

General Approach

During the infectious dendritic stage of HSV keratitis, treatment is based on reducing viral replication and spread using antivirals. Trifluridine was the mainstay antiviral for years. Like acyclovir, trifluridine is a nucleoside analog that interferes with cellular metabolism of virally-infected cells. However, trifluridine is poorly selective for virally-infected cells and is too toxic for systemic dosing. As a rule of thumb, if an anti-infective medication exists only topically, it is probably a sign of toxicity with systemic dosing. Even when only used topically, trifluridine can cause epithelial keratitis with frequent or prolonged use.

Zirgan (ganciclovir 0.15%, Bausch + Lomb) is the only guanosine analog topically available in the United States. This helps practitioners achieve effective antiviral dosing topically with less tolerance issues than trifluridine. Also, varicella’s susceptibility to Zirgan has opened up a topical treatment option for herpes zoster ophthalmicus.

|

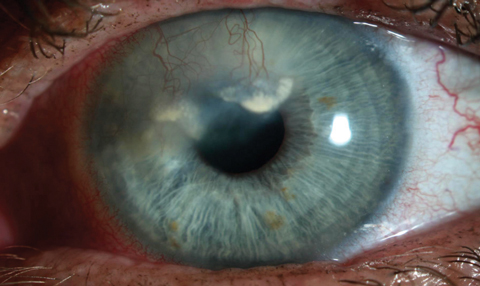

| This patient has heavy vascularization and lipid deposition secondary to herpetic keratitis. |

Clinically, I’ve noticed a tendency for practitioners to favor topical antivirals when dealing with HSV. Most think that if the problem is on the eye, dosing the medication directly is helpful. While the mindset that topical anti-infectives are superior to systemically dosed medications is accurate in some situations, such as with bacterial keratitis, it may not be the case in HSV. Meta-analysis of the limited research shows orals and topicals may be equivalent in dendritic HSV.1 I’ll usually lean towards topicals in cases of dendritic keratitis; however, when cost considerations come up, I do feel comfortable using oral medications as front-line therapy when dealing with any type of HSV keratitis. However, severe cases of infectious epitheliopathy or necrotizing stromal disease may call for both oral and topical treatment.

Corticosteroid use alone in inflammatory HSV manifestations increases the likelihood of recurrent infectious epithelial disease and further perpetuation of the herpetic cycle. As such, prophylactic dosing with antivirals is required any time a corticosteroid is used. When using a topical antiviral paired with a topical corticosteroid, drop-for-drop prophylaxis dosing is sufficiently conservative in most cases. When using an oral-topical pairing, oral acyclovir 400mg QID will suffice. As with all things, there is no magic dosage that will prevent all flare-ups, and even with both oral and topical antiviral prophylaxis, recurrences are possible.2

For long-term maintenance, oral prophylaxis of antivirals was established with the HEDS study, where it was shown to reduce recurrence of stromal disease by 50% in those with a history of stromal disease. Reports of resistance exist, but most cases of acyclovir resistance in HSV have occurred in immune-compromised populations, and resolution with acyclovir is still more common than resistance, even in cases where isolates have low susceptibility.3 Despite the HEDS-established protocol, effective dosing may vary. For most, the 400mg BID suggested dosing will be sufficient. However, some cases may require titrating upwards to reduce flare-ups, and some may require less frequent dosing.

Exceptions

While oral acyclovir and its derivatives are the mainstays of HSV keratitis treatment, oral antivirals should be limited or even avoided in some cases. Because these medications are excreted through the kidneys, predictable tissue concentrations are dependent on normal kidney function. Patients with renal failure or failing kidney transplants require altered dosing based on their renal function and weight. In this group, the medication is not excreted at typical rates, so it can systemically build up to extreme levels with standard dosing, leading to side effects. In these cases, practitioners can call the patient’s nephrologist and ask for “kidney-adjusted dosing guidelines.” An easier approach to avoid the renal consideration for acute disease is to use topicals.

ODs should avoid using topical corticosteroids when dealing with any infectious epithelial episode due to the risk of worsening the episode and increasing the likelihood of recurrence and stromal involvement.4 During episodes of herpes stromal keratitis (HSK), herpes endotheliitis and herpetic iritis, however, topical corticosteroids can be used safely and effectively. In some HSV keratitis cases, chronic topical corticosteroids may be required to keep inflammation under control.

|

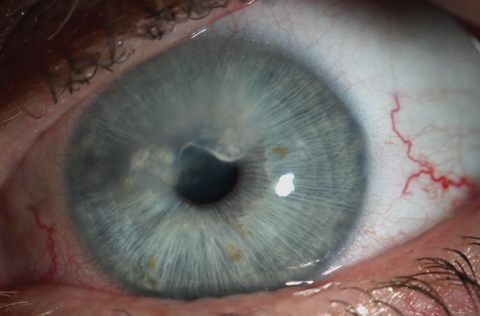

| At one month post-treatment, vessels are still present but markedly less perfused. This will likely require repeat treatments to maintain effect. |

Vision Loss

Scarring occurs for the roughly 40,000 cases of severe HSV-related vision loss encountered each year, and other treatment options are required.5

First, the two most common ways to remove a scar—transplants for deep scars and phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK) for superficial scars—carry risk of recurrence. Corneal excimer laser application is also a risk factor for reactivation, which may limit the appeal of PTK. In both cases, high-dose prophylaxis with antivirals leading up to surgery and continuing well into the postoperative period, combined with a quiescent pre-surgical period of several months, is advised.

Vascularization associated with herpetic scars further complicates treatment. PTK is not performed on vascularized corneas, and heavily vascularized scars carry a significant risk for rejection with transplants. Surgeons can limit most risk of rejection by performing deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty instead of PTK, but revascularization of the graft remains a concern.

When vascularization is a primary concern, bevacizumab may be dosed topically or intrastromally to reduce perfusion, but any well-established vessels are likely to re-perfuse with time. No herpetic scar is a perfect candidate for scar removal; however, assuming the surgeon is willing and the patient understands the risks, scar removal may be the only option for visual rehabilitation.

For patients with recurrent or severe endotheliitis, the cumulative stress will reduce the patient’s endothelial cell count and may ultimately create a decompensated corneal endothelium that requires an endothelial transplant. As with other HSV surgical interventions, heavy pre- and post-treatment antivirals are warranted in these cases.

Prevention

Vaccination for HSV is clinically unavailable. Promising animal models for both viral fragment and attenuated virus vaccines exist, and a human trial with a viral fragment (with middling results) has also been published—but in all cases only a small sample of research actually assesses ocular response. HSK may be a form of autoimmunity turned on by original ocular infection, and it is unknown how a vaccination, which may be preventative or therapeutic, could interact with this immune arc. In either event, it will likely be some time before a vaccination is available.6

This concludes our discussion on HSV. My hope is that you will always consider the possibility you are dealing with HSV for any unilateral keratitis you encounter, and also that you will be comfortable with the treatment options available. From a sheer numbers perspective, HSV is the most critical corneal infectious pathology to understand.

1. Wilhelmus K. Therapeutic interventions for herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD002898. |