Five years or so later, while working as lead researcher on a study of silicone hydrogel continuous wear at the CCLRU in Sydney, I became convinced. Eyes were white; in contrast to the expected vascularisation, there was vessel ghosting and virtually no microcysts. Wearers were happy, inflammatory events low and microbial keratitis (MK) extremely rare.1 There were some mechanical issues, notably SEALs and CLPC, but we had strategies to reduce those. Looked at from its clinical aspects, safe extended wear was indeed a reality.

The laboratory findings, on the whole, agreed. Higher levels of oxygen supply were linked to protection against infection in contact lens wear in several lab studies. Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) is the most prevalent organism in contact lens microbial keratitis in cool climates.2 PA binding to corneal epithelial cells is less common with higher oxygen permeable lenses.3 In addition, extended wear results in migration of Langerhan’s cells (dendritic cells that act as antigen presenting cells) into the cornea in animal models.4 More recently, a rodent model of contact lens infection found increased levels of dendritic cells in the corneal periphery as well as a higher incidence of MK with low compared to high oxygen transmissible (Dk) silicone hydrogel lens wear was found.5

In short, the modality looked quite promising. Practitioners were enthused about its prospects. Was it—as financiers say about stock market bubbles—irrational exuberance?

|

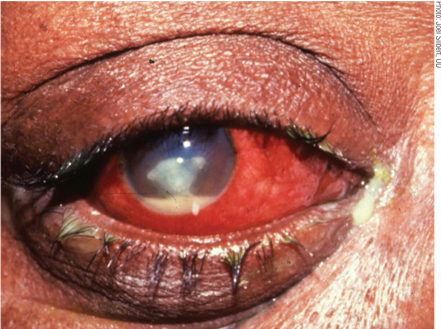

| Keratitis secondary to Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a potential adverse event of improper lens wear. Note the central ulcer, hypopyon, gross hyperemia and mucopurulence.

|

Risky Business

Silicone hydrogel continuous wear lenses hit the market in 1999. A large post-marketing study showed that MK rates were similar to low-Dk extended wear, and a meta-analysis of studies indicated silicone hydrogels had twofold increase in corneal inflammatory events.6,7

From 2003-2005, two concurrent, large-scale, epidemiological MK studies funded by the contact lens industry were conducted.8,9 The researchers confirmed that overnight wear, regardless of the lens type, increased the risk of MK by a factor of four.

Questions remained: Did the contact lens wearers who were new adopters of this technology—a trait linked to high risk taking—have poor hygiene practices? Maybe the practitioners, who were early-adopter prescribers, were less vigilant with patient safety and selection or were prescribing silicone hydrogel lenses as a problem solver? Did we have a different group of wearers, more at risk of adverse events in this early period? Certainly there was a precedent for this.

When disposable lenses were first introduced to the market in the early 1980s, the risk of MK was significantly higher than with conventional soft lens wear.10,11 As the market penetration of disposable lenses increased over the following decade, the relative risk decreased.12

It is probable that the population of wearers in the early period was dominated by early adopters of the modality who had been shown to take more risks and wearers prone to adverse events, as the lenses are likely to have been fitted as a problem solver by practitioners.6,12,13

It has also been postulated that overly enthusiastic practitioners who prescribed lenses during this period may have predisposed wearers to increased risks in terms of who they prescribed to and the advice they gave them.6

In 2009, my research team found high risk-taking contact lens wearers tended to be more non-compliant and may be at greater risk of corneal inflammation and infection because of poor lens care procedures.14 High risk taking was more prevalent, as expected, in younger individuals and males, and may explain some of the increased risk of adverse events in these groups of wearers.

Risk-taking personalities of medical practitioners have been investigated in relation to patient care in a number of studies. Higher risk-taking practitioners have been found to make fewer referrals, prescribe antibiotics less often, order fewer laboratory diagnostic tests, admit fewer cardiac emergency patients to hospital and generate lower costs per patient.15-19

We found that Australian contact lens practitioners scoring highly on risk-taking propensity prescribe lenses based on the same perceived importance of risk factors for adverse events and give similar advice to wearers as risk averse practitioners.20 It is unlikely that new adopter contact lens practitioners influence adverse event rates as new products are brought to market.

|

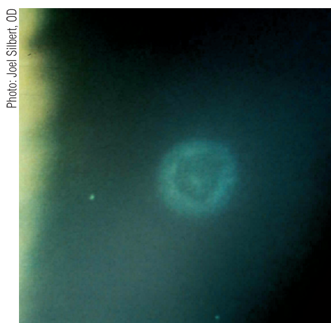

| A healed contact lens peripheral ulcer several months after initial onset. Notice the faded bull's-eye scar. |

Which types of patients should avoid continuous wear? Continuous wear is not advised for heavy depositors, with or without contact lens papillary conjunctivitis (CLPC). Daily replacement of contact lenses reduces the incidence of CLPC recurrence with both silicone hydrogel and softer moduli hydrogel lenses.21 While the predominant deposit on silicone hydrogel materials is lipid that can usually be rubbed off with surfactant, you don’t want wearers taking lenses out, introducing possible contaminants and then being tempted to reapply lenses without overnight disinfection.22 It is advisable not to fit wearers with active and recurrent anterior lid margin disease as the staphylococcal bacterial load is associated with contact lens peripheral ulcers.23

What behaviors should be cautioned when using continuous wear? Water contact should be avoided with all soft lens modalities because of the association with Acanthamoeba keratitis.24,25 Even though the risk of Acanthamoeba keratitis is low and varies depending on region, it is a devastating disease that can last months and sometimes years.26 It is not clear whether showering in lenses is an independent risk factor for infection, or whether it is linked to continuous wear.

In any case, it would be good practice to recommend avoiding splashing the eyes with water, and to wear tight-fitting goggles when swimming. Often, practitioners will advise patients to bring a supply of daily disposable lenses for holidays. This can be useful also as people tend to be out of their normal routine on holidays, and one study has shown a relationship with more severe infections.27

Wearers with less lens experience generally or, in the case of continuous wear in a new lens type, are more at risk of both corneal infection and inflammation.8 Handling difficulties may contribute to mechanically induced events in new wearers, but this would not likely be the case for those new to continuous wear. These findings point towards adaption of the anterior eye, which has been indicated in human studies, as evidenced by binding of Pseudomonas to corneal epithelial cells, surface cell shedding and epithelial thickness return to baseline levels over a 12-month period.3

Still a Sensible Option?

What types of wearers might really benefit from continuous wear? To name a few groups–– people with a love for the outdoors who camp a lot; those with lens-handling issues; and individuals whose ocupations or lifestyles benefit from long hours of wear, such as shift workers. When hand hygiene is an issue (e.g., on a camping trip), not having to touch the lenses is a distinct bonus. Difficulty in handling lenses can take up a lot of time for some individuals, such as men with large digits. The ensuing frustration can result in ocular surface damage and/or discontinuation of lens wear. During “on” weeks, shift workers can have little relaxation time. Not having to worry about lens care can be a lifestyle advantage.

There are many practitioners who have thriving continuous wear spheres of practice and report very few issues. However, it should not be a niche market. You don’t need the latest topographer or have to worry about precise lens fitting. You do need good communication skills and relationships with patients. Overnight lens wear still confers a higher risk of microbial keratitis, and patients must clearly understand the consequences of their choice. Still, compared to other life risks, it is low—about equal to the risk of dying of cancer in the US.28 Continuous wear can make a big difference to the quality of life of some wearers and, managed appropriately, can be a rewarding sphere of practice.

Dr. Carnt is an Australian Government Early Career CJ Martin Research Fellow at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London. Previously, she worked in private practice in Australia and the UK before taking a position with the Brien Holden Vision Institute in Sydney in 1999, where she held a variety of roles, including Principal Investigator on contact lens clinical trials. She completed a PhD in Epidemiology of Contact Lens Related Infection and Inflammation in 2012.

1. Sweeney DF, Du Toit R, Keay L, et al. Clinical performance of silicone hydrogel lenses. In: Silicone Hydrogels - Continuous wear contact lenses. 2nd ed. Edited by DF S. Oxford, UK: Butterworth Heinemann; 2004:164-216.

2. Melia B, Islam T, Madgula I, Youngs E. Contact lens referrals to Hull Royal Infirmary Ophthalmic A&E Unit. Contact lens & anterior eye. J Br Cont Lens Asso. 2008;31(4):195-9.

3. Ren DH, Yamamoto K, Ladage PM, et al. Adaptive effects of 30-night wear of hyper-O2 transmissible contact lenses on bacterial binding and corneal epithelium. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:27-39.

4. Hazlett LD, McClellan SM, Dacjs JD, et al. Extended wear contact lens usage induces Langerhans cell migration in cornea. Exp Eye Res. 1999;69:575-7.

5. Zhang Y, Gabriel MM, Mowrey-McKee MF, et al. Rat silicone hydrogel contact lens model: effects of high- versus low-Dk lens wear. Eye Cont Lens. 2008;34(6):306-11.

6. Schein OD, McNally JJ, Katz J, et al. The incidence of microbial keratitis among wearers of a 30-day silicone hydrogel extended-wear contact lens. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(12):2172-9.

7. Szczotka-Flynn L, Diaz M. Risk of corneal inflammatory events with silicone hydrogel and low dk hydrogel extended contact lens wear: a meta-analysis. Optom Vis Sci. 2007; 84(4):247-56.

8. Stapleton F, Keay L, Edwards K, et al. The incidence of contact lens-related microbial keratitis in Australia. Ophthalmology 2008;115(10):1655-62.

9. Dart JK, Radford CF, Minassian D, et al. Risk factors for microbial keratitis with contemporary contact lenses: A case-control study. Ophthalmology 2008;115(10):1647-54.

10. Buehler PO, Schein OD, Stamler JF, et al. The increased risk of ulcerative keratitis among disposable soft contact lens users. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:1555-8.

11. Matthews TD, Frazer DG, Minassian DC, et al. Risks of keratitis and patterns of use with disposable contact lenses. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:1559-62.

12. Keay L. Perspective on 15 years of research: reduced risk of microbial keratitis with frequent-replacement contact lenses. Eye Cont Lens. 2007;33(4):167-8.

13. Goldsmith RE. Personality characteristics associated with adaption-innovation. J Psychology 1984;117(2):159-165.

14. Carnt N, Wu Y, Keay L, Stapleton F. Risk taking propensity in contact lens wearers. British Contact Lens Association Annual Clinical Conference. Manchester; May 2009.

15. Franks P. Why do physicians vary so widely in their referral rates? J General Intern Med. 2000;15(3):163-8.

16. Grol R, Whitfield M, De Maeseneer J, Mokkink H. Attitudes to risk taking in medical decision making among British, Dutch and Belgian general practitioners. Br J General Pract. 1990;40(333):134-6.

17. Zaat JO, van Eijk JT. General practitioners' uncertainty, risk preference, and use of laboratory tests. Med Care. 1992; 30(9):846-54.

18. Pearson SD. Triage decisions for emergency department patients with chest pain: Do physicians' risk attitudes make the difference? J General Int Med. 1995;10(10):557-64.

19. Fiscella K, Franks P, Zwanziger J, et al. Risk aversion and costs: a comparison of family physicians and general internists. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(1):12-7.

20. Carnt N, Keay L, Willcox MD, et al. Pilot study of contact lens practitioner risk-taking propensity. Optom Vis Sci. 2011; 88(8):E981-7.

21. Stapleton F, Stretton S, Papas EB, et al. Silicone hydrogel lenses and the ocular surface. Ocular Surf. 2006;4(1):24-43.

22. Jones LW, Senchyna M, Glasier M, et al. Lysozyme and lipid deposition on silicone hydrogel contact lens materials. Eye Cont Lens. 2003;29:s75-9.

23. Wu P, Stapleton F, Willcox MD. The causes of and cures for contact lens-induced peripheral ulcer. Eye Cont Lens. 2003;29(1 Suppl):S63-66; discussion S83-64, S192-4.

24. Radford CF, Minassian D, Dart JK. Acanthamoeba keratitis in England and Wales: Incidence, outcome and risk factors. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:536-42.

25. Joslin CE, Tu EY, McMahon TT, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of a Chicago-area Acanthamoeba keratitis outbreak. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;142(2):212-7.

26. Dart JK, Saw VP, Kilvington S. Acanthamoeba keratitis: diagnosis and treatment update 2009. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009,148(4):487-99 e482.

27. Edwards K, Keay L, Naduvilath T, et al. Characteristics of and risk factors for contact lens-related microbial keratitis in a tertiary referral hospital. Eye. 2009;23(1):153-60.

28. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Vital Statistics System: 2012. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/mortality_tables.htm#mortality. Accessed May 31, 2013.