Building a practice around GP, scleral and other specialty lenses requires dedication and an ongoing need to remain up-to-date and proficient. This persistence will be necessary when you come across fitting challenges and busy scheduling. Review of Cornea and Contact Lenses hosted a roundtable discussion among several experts and moderated by Christine Sindt, OD, to help novice practitioners who are serious about medical lens management gain confidence. The pros also discuss what continues to be a thorn in their side and what priorities they maintain as their practices and expertise evolve.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

|

|

Remind patients to be gentle with the DMV inserter. Photo: Jeffrey Sterling, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

PART I: Declaring a Focus in Medical Contact Lenses

Dr. Sindt: I tried to pull a group of people in different types of practice settings with different perspectives about medical contact lenses. We’ll talk about why they’re in their particular practice setting, their view of the role of medical contact lenses, how each participant got going and what motivates and inspires them.

When you’re in private practice, you must recruit or market a little bit more by going out and talking to other practices about recruiting to get those patients in the door vs. when you’re in a university practice like I am. There are days when I feel like, “Whoa, somebody turn off the spigot of these medical contact lenses.”

What led you to medical contact lenses? Tom, why don’t we start with you? To you, what is a medical contact lens, and how did you get there?

Dr. Arnold: I got started by my cornea specialist, who I had a relationship with since I graduated. He started his medical practice; I started my optometric practice. I fitted the standard lenses, the little mini cones and some hybrids. I knew about sclerals, but I didn’t really pursue them. I had a busy practice. I was going, “I don’t have time for this stuff.” But I had sent my cornea specialist a couple of people I thought needed penetrating keratoplasties (PKs), and he said, “No, you need to fit them in sclerals.”

And I didn’t know anything back then. Soon, here comes the fitting set and my next cone patient. I said, “Well, I have a new lens. I don’t know much about it, but it’s supposed to be good. Would you like to try?” And I was just very lucky that after I put those first lenses on the patient, she just went, “This is amazing. Best thing I’ve ever done.” I was off to the races.

Dr. Sindt: What kind of commitment do you think people need to make, and how do you get to that point where you’re going to make that commitment?

Dr. Woo: When I completed my contact lens residency and had just started in private practice, similar to Tom, where I was seeing everything except for specialty lenses. I didn’t do anything at first. We started slowly integrating specialty lenses into a large private practice setting, and then over the years we grew and grew. By the end of it when I sold the three practices, I think about 25% of all of our income was from specialty lenses.

At some point, I had a come-to-Jesus moment where I was trying to come up with my ideal day. And I said, “Well, I’m happiest on the days where I just see specialty patients or I see a majority of specialty lens patients—whether it’s new consults, fittings, troubleshooting. I love it all.” So, then I thought, “Well, maybe I just want to do specialty lenses. Is that even possible? If I want to do that, then I’ve got to move to a bigger city.”

And that’s how Las Vegas came into play. I said to myself, “Oh, there’s no one fitting EyePrint here,” so that’s a huge opportunity. “Oh, there’s no fellows of the Scleral Lens Society in town,” that’s another huge opportunity. “No one has a scleral topographer in all of Nevada!” I know a lot of doctors were fitting sclerals out here, but I don’t think anybody was doing it at a very high level, and that’s where I took the plunge and opened up a practice just dedicated to specialty lenses.

Yes, it takes a lot of guts, and you do need to have a lot of patience and a lot of tolerance for risk, I would say. I had access to a lot of resources to get that started. Past webinars from the Scleral Lens Education Society and also joining social media groups such as Scleral Lens Practitioners and Business of Scleral Lenses were very useful. Also attending meetings such as Global Specialty Lens Symposium and the scleral lens tracks from Vision Expo helped greatly.

I’m always happy to share if somebody does want to go down that path, to advise them on what needs to happen or how to slowly integrate it in. You know, I’m happy to talk about both sides of it.

|

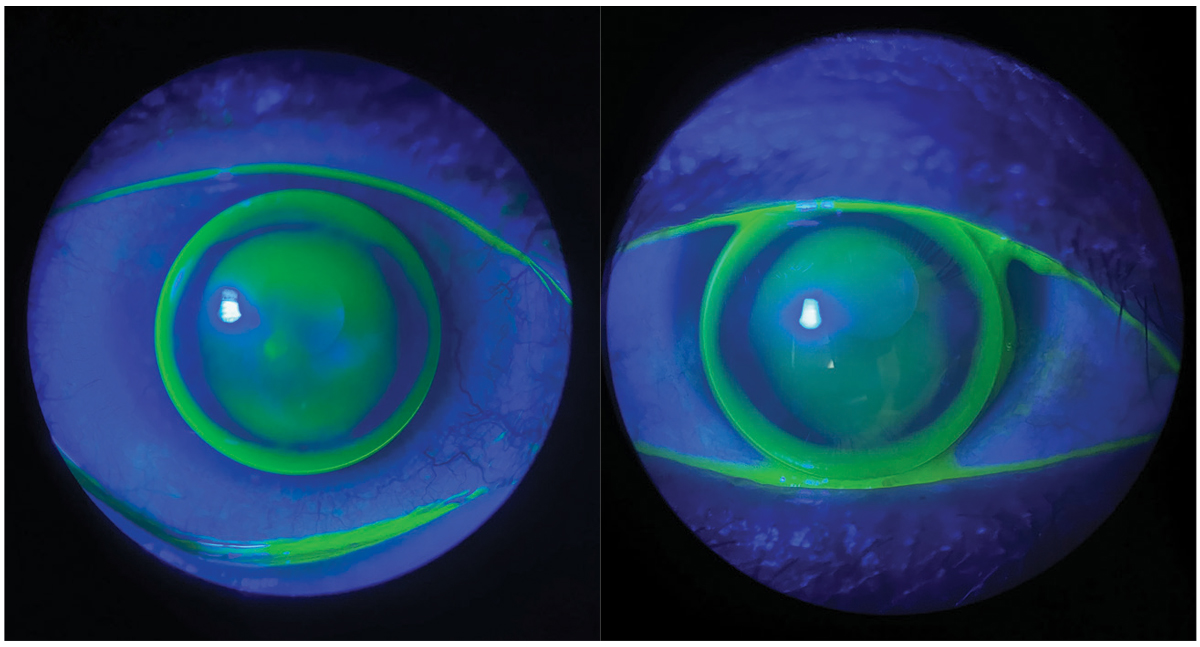

Scleral lenses fitted on a patient with post-refractive surgery ectasia. Photo: Christopher Lopez, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Dr. Sindt: I talk to doctors who say, “Oh, I do maybe one or two specialty lens fits a day.” Do you think it’s easier to integrate it into a bigger practice, or the more you do the easier it becomes? And I guess this leads into the dabbler question—is it possible to be proficient but only see a small number of cases?

Dr. Woo: I think the more experience you have with something, you just naturally become an expert in it. As far as the dabbler question, I’d love to hear from the group, too. But I used to be on the side of believing, “Anybody can do sclerals, and in fact everybody should do them. You know, you might have one patient a year, but that patient’s going to be excited to have access to you.”

Now I’m totally in the other camp, where I feel that if you don’t love doing it and you’re not doing it routinely, send it to someone else. I follow that same protocol. I don’t like to do regular eye exams with kids, so I send them to my friends who love doing them. I’m not good at vision therapy or low vision, so I send them to people who enjoy doing those things and are very good at it. So I’ve switched camps.

Dr. Miller: I’m with you, Steph. One and done is fine in some situations if that’s the most realistic way to serve the patient’s needs, but are we causing more of a problem with some practitioners not being well-versed in fitting lenses or understanding the pathology behind what they’re fitting.

I am totally in the camp of advocating that practitioners need to know the field well and commit to continued learning. Products are constantly evolving, ways that we manage disease are constantly evolving. You need to be well-versed with both of those situations if you’re going to be doing sclerals.

Dr. Arnold: That is so true, Heidi. What has energized me is that there is always something new to learn, always something evolving.

Chris was helping me with an EyePrint, and it was very difficult. Great patient but very challenging case. I’d done pretty much everything I thought I could do, and I called Chris. We went through the case, and she said, “You know, some patients are just hard.” I’ve never forgotten that.

Dr. Noyes: When sclerals first came out, many people reacted by saying, in effect, “Oh, here’s a new keratoconus lens.” But as we all know, the breadth of what we use sclerals for has just exploded: graft-vs.-host disease, severe dry eye, scars, all sorts of stuff. I think that all these people who wanted to get into sclerals were originally thinking, “Sure, I can do this new GP lens,” and then they didn’t really realize the much more broad range of uses, the side effects, warning signs to look for, the differing fitting philosophies—all the nuances of the craft.

|

|

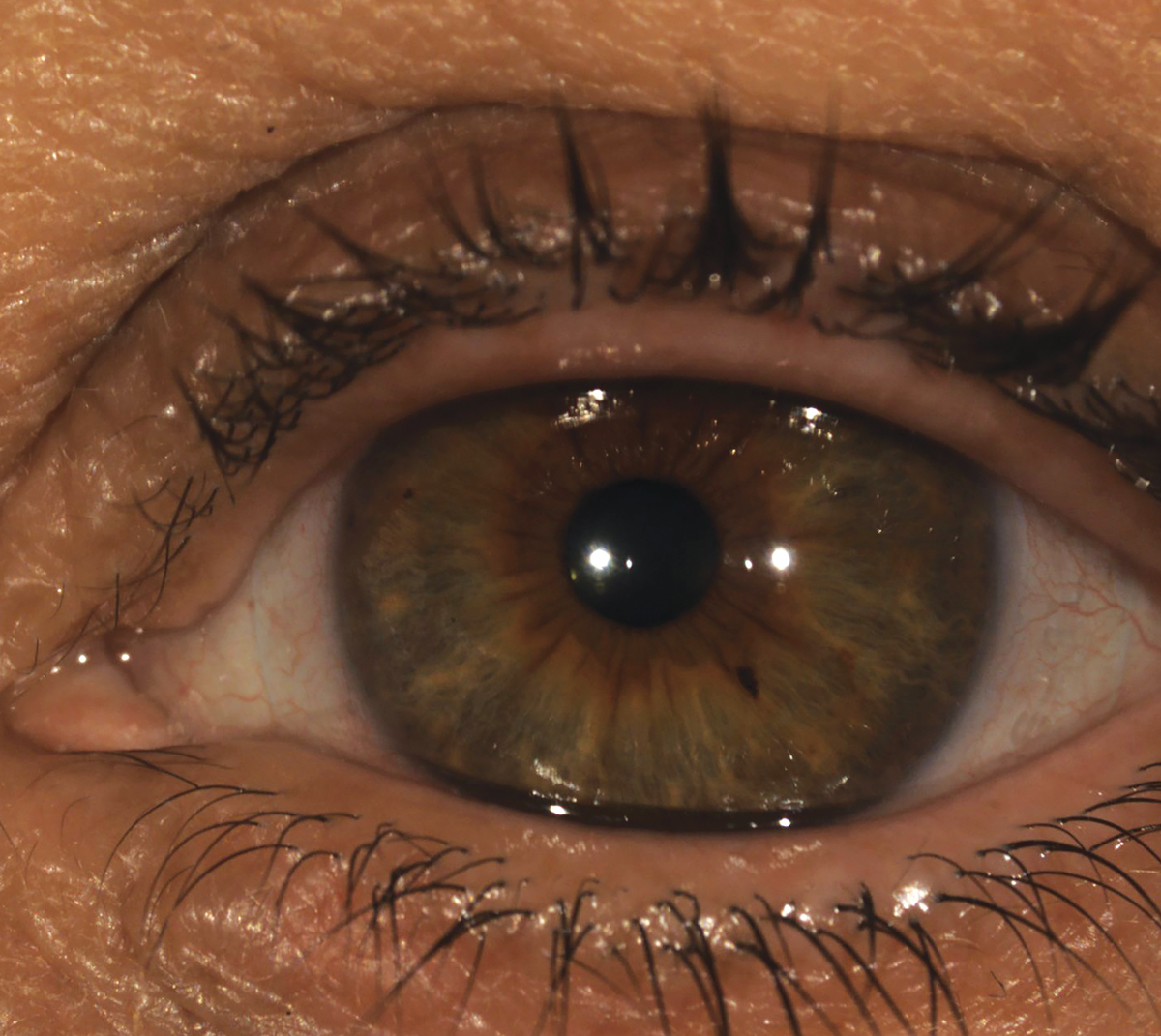

A well-fit scleral lens over an eye that has undergone a corneal transplant. Photo: Tom Arnold, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Dr. Woo: This might be a stretch of an analogy, but would you go to a doctor who does heart surgery once a year? Do you want that doctor doing your heart surgery? I personally would want to go to a doctor who’s well-versed and sees these types of patients every day because I know that they’ve seen basically all the things that can happen and they would know how to manage my case in the best way.

Dr. Miller: I feel like most of my referrals come from a patient who had tried a scleral or a corneal GP lens and felt they weren’t a good candidate because the result was subpar. That’s unfortunate because I feel we have to start over from square one. You don’t want to throw your colleagues under the bus. I end up treating these cases as if they’ve never worn a lens before: “Let’s start back to basics. We’re going to train you from beginning to end.”

So, I wish people didn’t dabble because it also puts you in a tough situation, though I do understand the challenge on their end—you’ve got to start somewhere.

Dr. Andrzejewski: I remember a patient a few years ago. He came in saying, “Sclerals are the worst thing ever. I like those hybrids that you fit me in years ago.” Now, this was before his disease progressed and before he had Intacs. I examined him and said, “Yeah, you need sclerals.” He pushed back, “Those things are terrible.” I had to explain that a good-fitting scleral lens should be quite comfortable, that if it’s not, something is not right.

It goes back to knowing what you’re doing because otherwise it sours a patient on the modality. I just had a young guy yesterday who was here for a first-time appointment. His attitude at the start was, “I’ve heard those hard lenses are terrible, I want a scleral.” After I showed him what a scleral was, his knee-jerk reaction was, “I don’t want that, that’s too big.” But we tried it on and within 15 minutes, he was adapting well and ready to try it.

Sometimes patients develop preconceived notions about specialty lenses because of what they’ve read online, what they’ve heard from friends or other patients or doctors.

I say, tell fellow OD colleagues and students who are interested in specialty contact lenses and want to incorporate this into their practice: “You can learn, with some dedication, how to fit scleral lenses and be proficient at it. It takes time and patience. The more you start fitting sclerals and specialty lenses, the other challenge is integrating it into practice; the challenging thing is the patient flow, checking the insurance and getting all the logistics worked out so that patients can have a smooth experience.”

If you’re dabbling, you may not get to master these things, and there’s no consistency to your method. It would mess up your day to have a full general book and then, all of a sudden, you’ve got this scleral lens fit in the middle of it. So, I think the challenge of dabbling has to do as much with how you run your clinic as acquiring the technical skills.

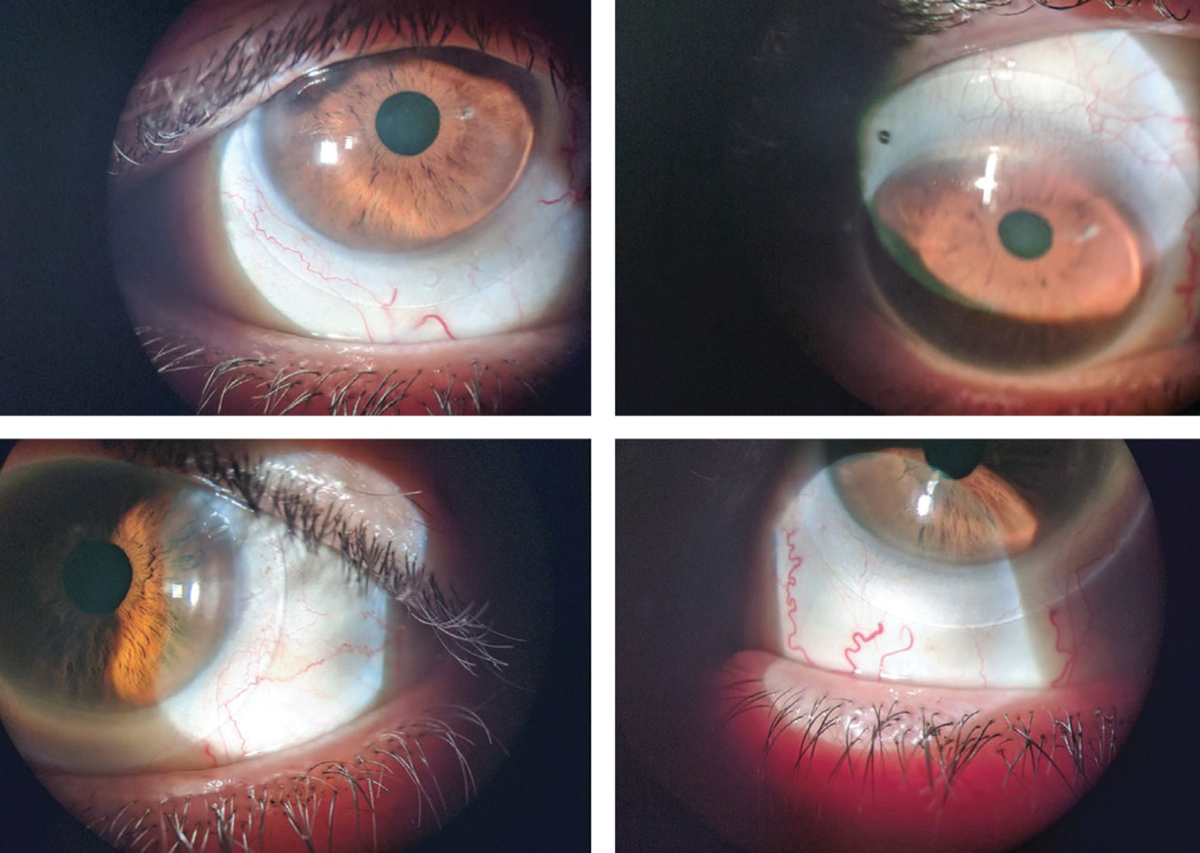

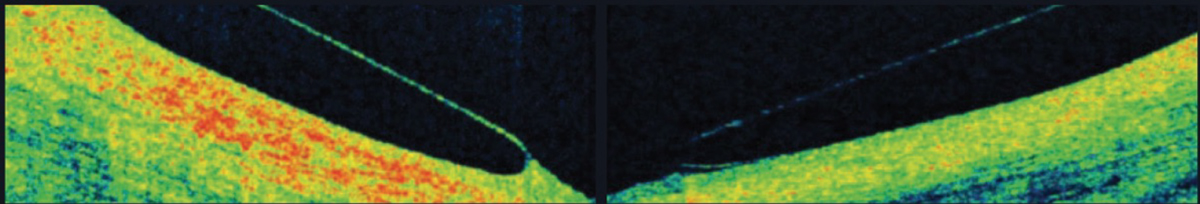

|

|

AS-OCT shows a scleral lens edge with slight impingement into the conjunctiva (left) and an edge that lifts away from the conjunctiva (right). Photo: Chandra Mickles, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Dr. Sindt: How do you all feel about GP lenses and where you’re placing them in your practice at this point? Are you all-in for sclerals? Do you feel like there’s a place for GP lenses? Do you feel like you’re using GP lenses more or less now?

Dr. Woo: All of us love corneal GP lenses, and if you ask some people that are dabblers, like Heidi was saying, they’re never going to fit a GP lens. But all of us love GP lenses because we know where they fit in.

Dr. Andrzejewski: I explain to my fourth-year interns that, if there’s mild keratoconus and/or there’s a nice central cone and it’s not too steep, then I can fit a corneal GP so much faster than a scleral. Chair time is a valuable thing in practice.

Dr. Arnold: I agree. I think getting really into sclerals energized my GP practice. It made me bolder. For patients coming in with a custom toric or wanting a custom soft toric, I often say, “Look, I’ve analyzed this, I’ve looked at all this data—you would be great in a GP.” I love fitting GPs. In many cases, patients see better with them.

Dr. Noyes: I’ll take the contradictory side. Although I do a lot of GPs, I usually lean a little bit more on sclerals. The main things that will take me to a GP: (1) they’re a little more affordable and (2) if the patient doesn’t qualify for sclerals. But I will lean a little bit more on sclerals than GPs mainly just for patient comfort. Also, we do a lot of EyePrint lenses, and those are just perfect every time, so that makes it a little easier, too.

Dr. Sindt: When approaching medical contact lens fitting, we manage a lot of things in our practices. So I’d like to hear from you guys about other things that you have to manage besides just the contact lens.

Dr. Woo: That’s like what Heidi was saying—fitting lenses is the easy part. It’s managing the disease and the patient’s emotions and personality and expectations, that’s what’s hard about specialty lens fitting.

|

|

Scleral lens application can be a challenge for some patients, leading to bubbles and eye irritation if the patient isn’t aware of their presence. Photo: Tiffany Andrzejewski, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Dr. Sindt: What steps did you take to build a medical contact lens practice?

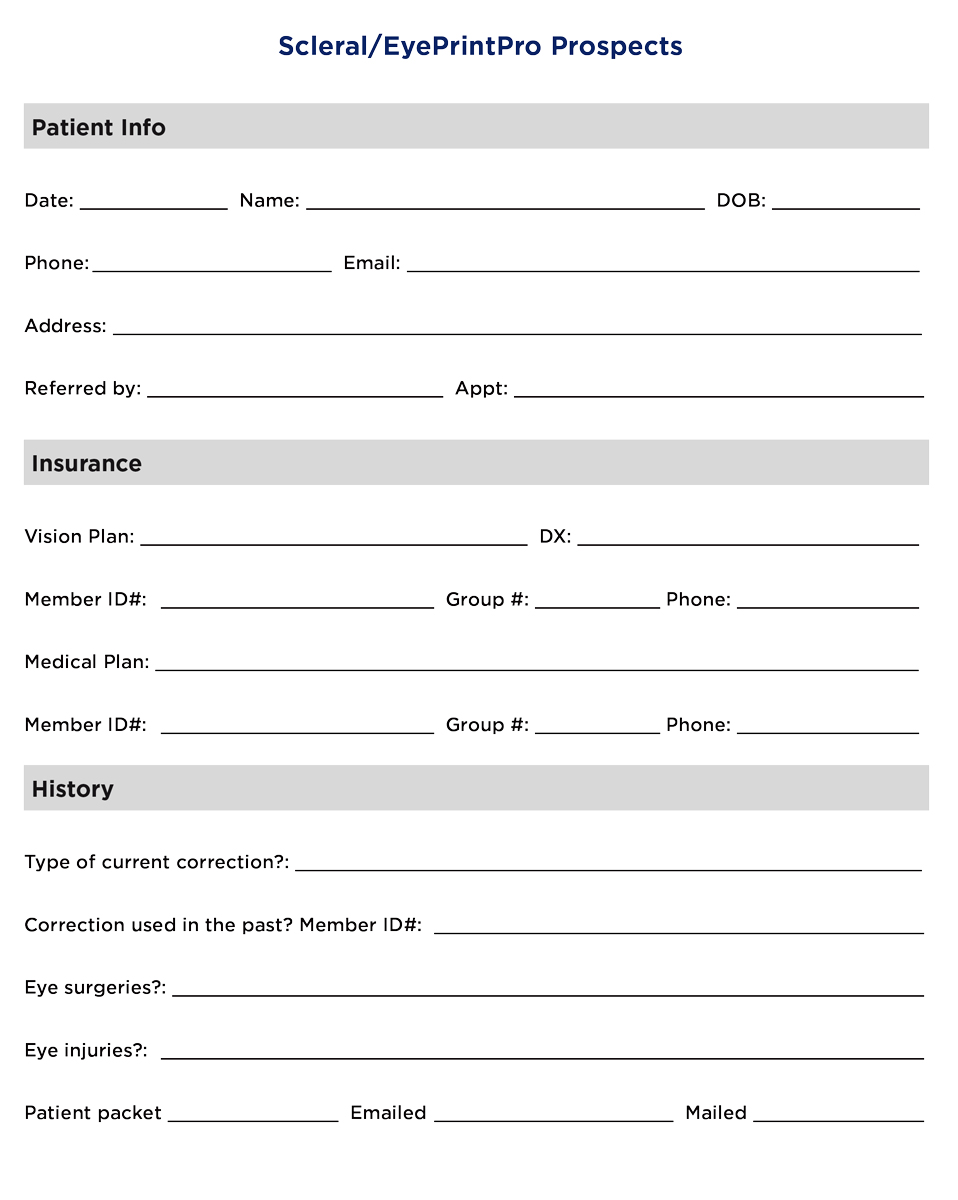

Dr. Arnold: I made a packet that included my CV, a little about the clinic, a little about scleral lenses, some medical billing type information and I visited other practices with that. (See “Resources for Scleral Lens Wearers” and “Scleral/EyePrintPro Prospects”) I targeted anterior segment surgeons, the cornea people, and I would set up appointments. I would go talk, myself. I did not send staff. It’s important that you go yourself. And I reached out to all the ODs in my area.

You keep reaching out and make sure you touch base with them. That’s how I built it. It takes work. It was maybe three years of pounding the pavement consistently.

Dr. Andrzejewski: I work with ophthalmology, and cornea specialists in particular. In the Chicago area, while some patients may come to the practice to see a cornea specialist, they stay because of us optometrists. I found that what really helped grow my practice within the system is, when I’m seeing a patient referred by an outside ophthalmologist or any other outside eyecare practitioner, I send back a letter saying, “I saw your patient, here’s an update of what’s going on with them. I’ll continue seeing them for their specialty lens needs, but I will refer them back for their other eyecare needs.”

That led to those other doctors, especially from outside our practice, now referring to me because they can entrust me with their patients’ contact lens and vision needs and they’re not afraid of losing a patient.

I have found that this has helped grow my practice within the practice and that I get more referrals from not only outside ODs but also outside ophthalmologists.

Dr. Miller: The common theme I’m hearing from everybody here is to create your practice with a lot of openness so that referring doctors feel that there’s communication and won’t feel threatened that it’s a power play of taking the patients. The focus stays on what is in the best interest of the patient, and communicating back and forth keeps that best interest going forward.

|

|

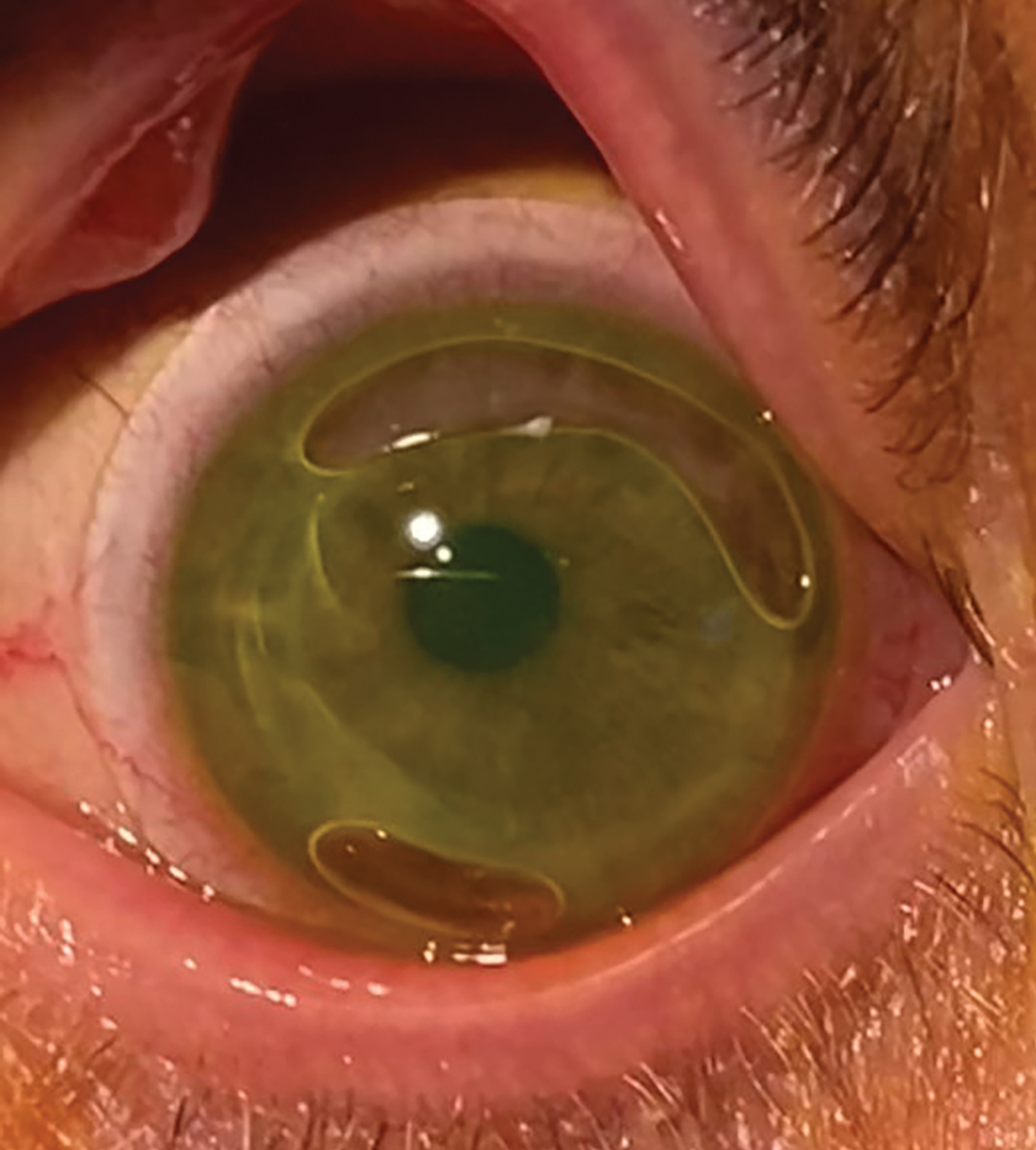

Scleral lens for a keratoconus patient with corneal Intacs. Photo: Heidi Miller, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

PART II: Medical Lens Fitting Issues, Complications and Patient Compliance

Dr. Sindt: How do you decide between fitting a GP vs. scleral lens? What’s your decision tree?

Dr. Miller: I’m paying attention to the person themselves. When I’m having a conversation and giving instructions, what is their feedback? Because there’s a lot of maintenance in sclerals, and there’s a lot of things you need to follow. Are they well-suited to it?

And because I’m comanaging really closely with our cornea service, a lot of times I get information on the transplants or what their corneal endothelium status is, things like that. So, I might do a corneal GP because I don’t think they’re going to be a great scleral lens candidate based on the likelihood of edema or complications in that regard.

Dr. Sindt: Let’s discuss scleral complications. I generally feel that typically a complication from a GP lens is, “Oh, it popped out,” or, “Oh, gosh, you’re dry.” The worst complications are things like diffuse lamellar keratitis, corneal abrasion, vascularized limbal keratitis or something along those lines. Fortunately, they’re rare.

Dr. Woo: I am not proud of it, but I’ve had a few corneal transplant rejections. We did everything we could initially to identify the patient as a good candidate.

Usually with transplants, I try to put them in a GP if I can just because they’re safer for the eye long-term. But let’s say they tried GP lenses or their corneal transplant is so irregular no GP lens is going to stay on, it just immediately pops off. There’s a variety of reasons. But we’ve taken all the measurements, checked their endothelial cell count, looked at the transplant and talked with the surgeon; everything seems like it’s a go, but their transplant just doesn’t like it and starts rejecting.

What I’ve learned from that is you’ve got to monitor transplant patients very carefully, even if you think they’re the best candidate, have done all the testing and even if the surgeon referred them directly to you for a scleral lens. You still have to be very upfront with the patient in letting them know the risks and benefits.

So, I am very upfront, and everything is written down. I go through all the things that we’ve done to determine that they are a good candidate, but I articulate the risks. I go through everything that could happen, and I think it’s important that they’re aware of all that, because they’ve already been through so much with this transplant situation. If it seems like the benefits outweigh the risks, then they go ahead and we go for it, and we just have to monitor them carefully.

|

| A patient wearing a custom scleral lens called the Latitude (Visionary Optics). Photo: Stephanie L. Woo, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Dr. Sindt: What I’m hearing you say is that it’s not about how to fit the plastic, it’s more about how to manage the problems.

Dr. Woo: Right. It’s not about fitting the patient; that’s easy. It’s everything that comes after that; the dispensing visit, the training, all the follow-up care, managing the health of the eye, monitoring the underlying issue, managing the personality, the emotions.

You’re right, Chris, it’s all of this stuff that happens after the initial fitting.

Dr. Miller: I’ve had a few patients I’m convinced were self-induced hydrops. Maybe the lens was too tight or they weren’t putting the plunger down at the end, resulting in suction forces. But then they disappear, and all of a sudden, they’re back in your chair and they have hydrops. And I’m convinced it had to have been some sort of mechanical thing that caused it.

Dr. Arnold: Handling is so important. I had a very large man—a big, strong guy—and he was just brutal with his lenses. Once he came in and he had popped all the vessels in the perilimbal loops, and he had just blood up into his cornea. It wasn’t in his visual axis, but it was in the cornea. It wasn’t hyphema, but it was pretty ugly. I said, “Look, you’ve got to learn to be gentle.”

Dr. Sindt: So, let’s talk about that perilimbal area there for a second. Because again, that’s an area that no other type of contact lens affects. You’re not going to get that with a soft lens or a GP.

Dr. Andrzejewski: For limbal stem cell deficiency, you don’t want to touch the limbus, so it makes sense to fit the patient in a scleral. But when things go wrong with a scleral, then you sit there and think, “Oh, now what do I do?” That’s the toughest thing in the book. Sclerals can be wonderful, and I’ve seen it reverse limbal stem cell deficiency in my own patients, but you’re right—if you’re not careful, it can cause it or other complications.

Sometimes it’s very easy to blame the plastic when in fact it’s the disease, the eye, the underlying pathology, autoimmune conditions or, yes, the patient’s own compliance. It’s very easy for people to turn around and say, “Oh, it’s your fit that went wrong, it’s the lens,” but everything looks absolutely great at the slit lamp. It’s challenging.

Dr. Sindt: I struggle with this idea of the tear exchange. I’m glad you brought that up. I’ve been fitting scleral lenses for 25 years or more, and so I’ll tell you the early fits were just really bad.

We had no way of even cutting toric peripheral curves. The patient would blink, the lens would move and fluid would go in under. However, we rarely saw limbal complications. You never saw the complications that I see now. And I think a lot of it was tear exchange—they had good tear exchange underneath the lenses.

So, I wonder what the group thinks about tear exchange. In online discussions these days, I hear a lot of people say, “Put fluorescein over the lens, and if you have leakage under the lens you have to tighten up that area of the contact lens.” Unless they’re getting massive amounts of mid-day fogging, I don’t necessarily want it to be 100% perfectly sealed because I think that negative pressure underneath the lens that is trapping inflammatory products causes probably most of the limbal stem cell deficiency that I see. We used to call it the toxic swamp, what’s underneath the contact lens.

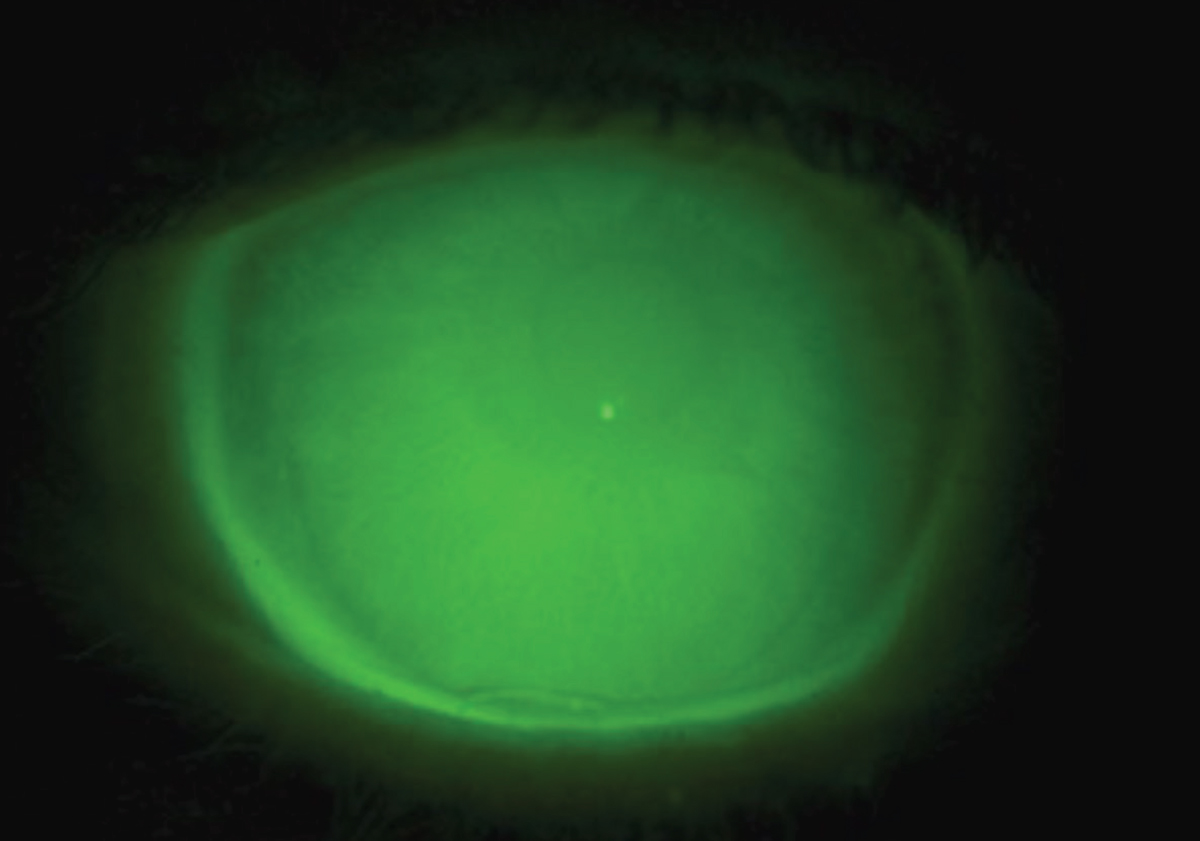

|

|

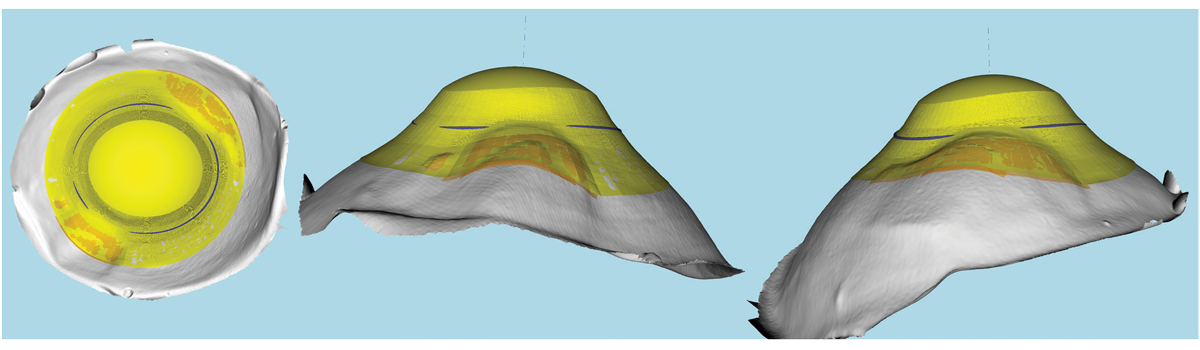

This is a 3D representation of an elevation-specific freeform impression-based EyePrint lens. Photo: Marcus Noyes, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Many of our colleagues talk about tightening the periphery to reduce mid-day fogging. Where do you stand on that?

Dr. Arnold: We all know the pros have been fitting very large lenses with very high clearance for a long time on the most complicated cases. Having said that, I try to adhere to good practices, but as long as a lens clears and it’s reasonable, I’m not going to fit a lens and be satisfied with 500µm of clearance, but I don’t sit and have an ideal clearance for any one lens. I do agree I want some tear exchange.

We monitored that in our office during follow-up visits; the patient would come in, the tech would check their vision, and they would dab some fluorescein on the bulbar conjunctiva before they took them back. They would do an OCT, and then I would see them. I would expect to see some fluorescein coming through in the fluid reservoir after 15 or 20 minutes. So, I don’t fit super tight, and I don’t lose sleep at night trying to get some ideal clearance.

Dr. Gelles: It all depends on the physiologic response and what the patient’s wearing the lens for. In some, a little trickle can be good. Some individuals that are just type-A.

Dr. Sindt: He does practice on the east coast.

Dr. Gelles: For me, I’m apt to just tighten it down in the area of misalignment to eliminate their worries, if it’s not going to cause a health concern. But it depends on how long it’s going to take for that fluorescein to get under the edge. If I paint it on the front of the lens and they take one blink and the whole chamber is filled with fluorescein, I know it’s just a bad fit.

Dr. Woo: I think too many doctors chase the fit to perfection, and I think I did that in my residency, too—calling the consultant constantly and making a thousand changes on each patient. Then, 20 lenses later, I realize lens number three was probably just fine for them. Now, if I see a tiny imperfection in the fit, I take it in stride. If the patient’s doing well and their eye is healthy, they’re seeing great, let them go. Stop making these tiny little changes and wasting your time, wasting the patient’s time.

Dr. Andrzejewski: And wasting lab resources.

|

|

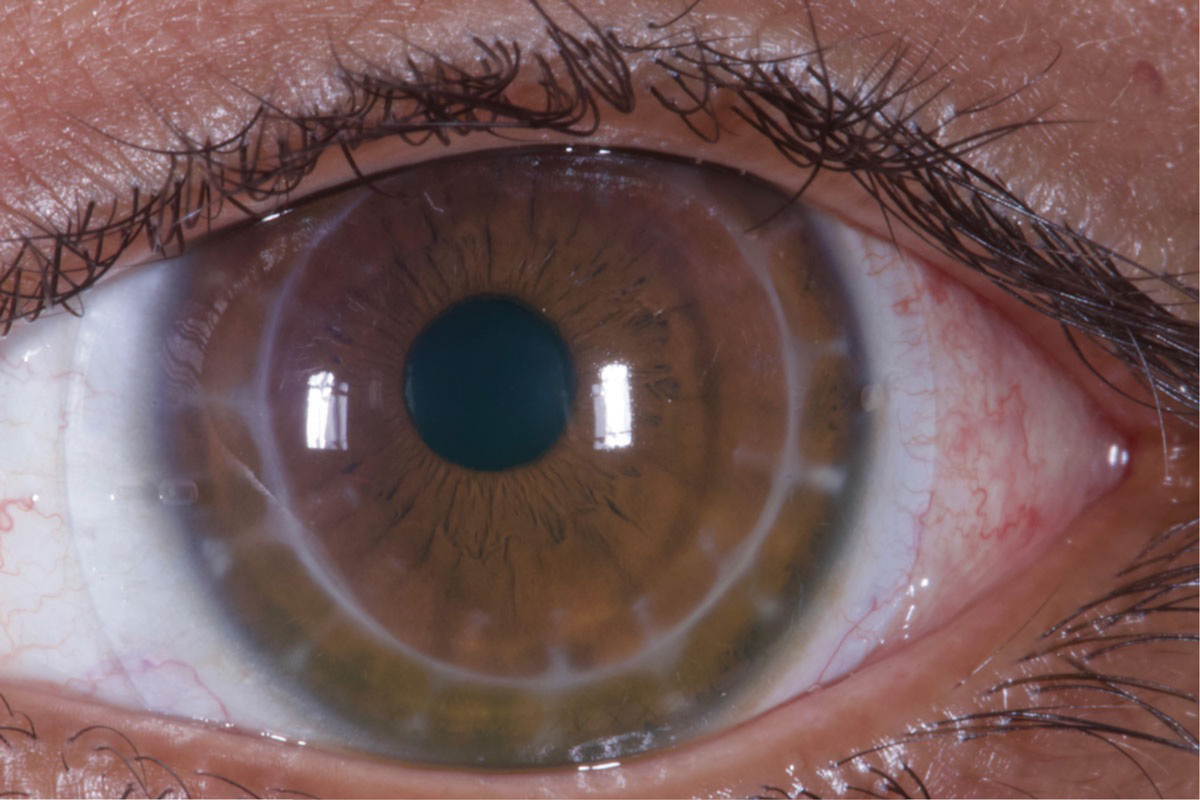

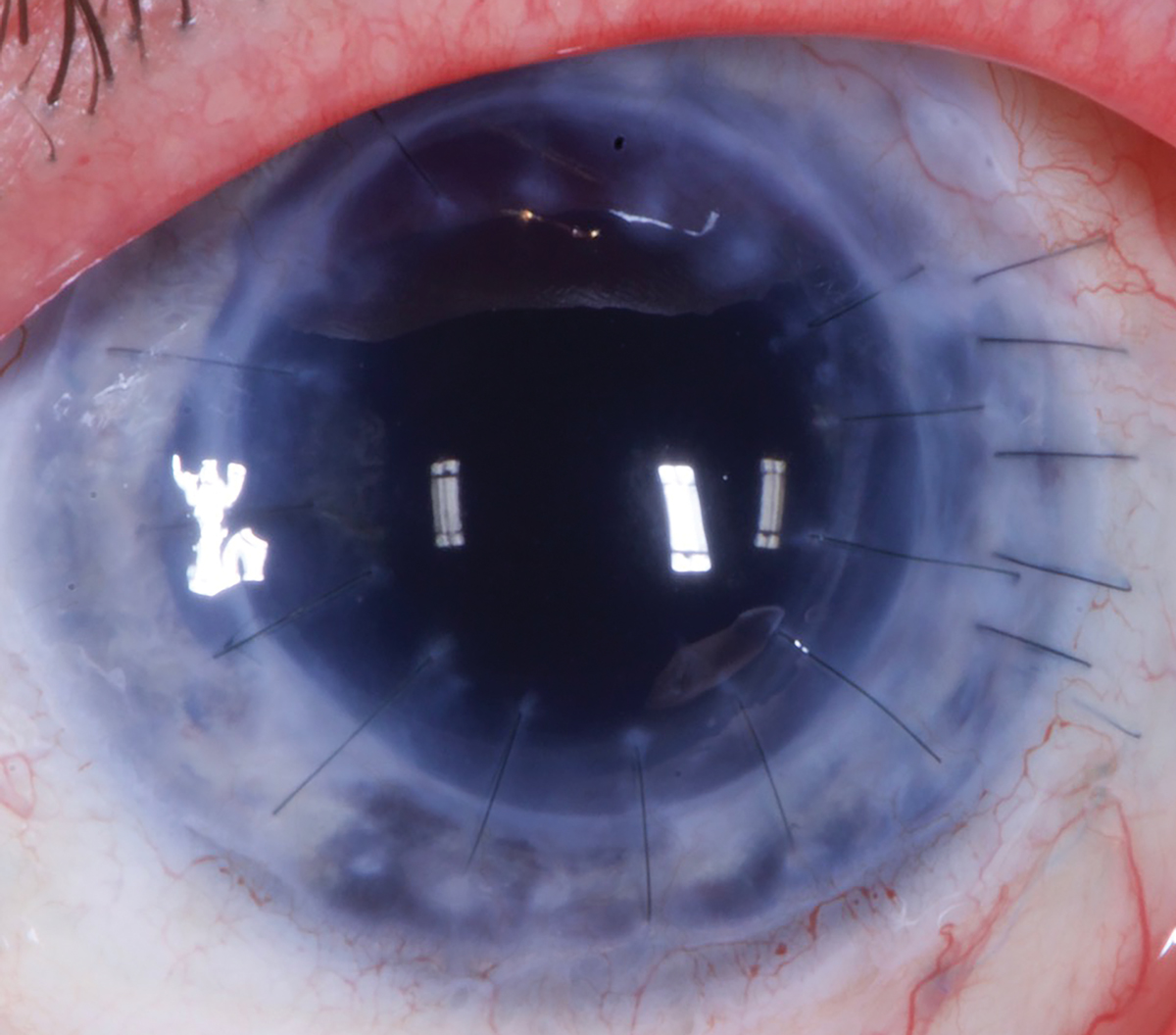

In PKs, monitor for edema and consider a larger lens. Photo: Tom Arnold, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Dr. Gelles: I want to throw one interjection into that, though. The vast majority of the patients who come in to see me have seen somebody else already, and usually they’ve had complications with their fit.

Yesterday I had a case of neovascularization like I had never seen before. I asked her about a history of viral infections or any inflammatory or autoimmune diseases that might be in play. Not one. I looked at the notes from five years ago, and the fit reportedly did look good then.

So, the issue is, how perfect do you want to be or should a fit be? For me, I don’t let the patient out of the office until I know that even if they showed up five years down the line, I’m not going to have a train wreck on my hands. This is especially on my mind coming on the heels of COVID. That patient never made it back to the original practice during all that time.

Dr. Sindt: What did the lenses look like?

Dr. Gelles: They were small and resting on the limbus. I used to think that the Boston Foundation for Sight recommendation of a big and loose fit was a little silly. I can get success with a 15mm or a 16mm, what does it matter? Nearly every single lens that I fit back in the day in the range of 14.8mm or 15.5mm has ended up with problems. Breakdown at the limbus, deep trenching impression rings, all sorts of issues. Lo and behold, “large and loose” is where I ended up.

Every single lens I fit right now is 18mm to 20mm, every single one. Most lenses I see that are 15mm to 16mm in diameter leave a giant impression ring and generate a lot of patient complaints: “When I take my lenses off, my eyes are red and irritated.”

They all have staining around their limbus. It’s just inherent to it: not enough haptic surface area to spread the lens force over so the lens sinks into the conjunctiva, thus the impression ring forms and limbal clearance is lost. You may think you can remedy that with ease when you see them at follow-up—“Oh, I’m just going to raise your limbal clearance a little bit more”—and then you do that again the next year and the next year. A few years in, you look and say, “Gosh, my haptic is really heel down and I keep having to bring the limbus up.”

Dr. Arnold: Elbow, yes.

Dr. Gelles: There have been very small things that early on I’d let go that, three years later, are a problem. Conjunctival hypertrophy, for instance—maybe it starts as just a couple fine vessels being compressed at very small, like less than a millimeter area at the lens edge.

No big deal, right? I’ll see them back every six months for routine follow-up, but three years later, “Wow, that gigantic granuloma wasn’t there before.” Some things smolder and then become a problem.

|

|

Prioritize proper clearance and fit over leakage when using sodium fluorescein. Photo: Brooke Messner, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Dr. Sindt: Do you think it’s hard to see your own problems?

Dr. Gelles: Not really. I would put it this way since I’ve seen many patients and thus patients with problems induced by lenses, both fit by me and others, even from doctors who I really respect and know are skilled. Over time, seemingly little things can become big issues, so mitigate them when they are small. Be diligent about follow-up and early to react.

It can be a challenge, though; some patients disappear during the fitting and fall into the “I’m comfy and can see. I’m done!” mentality and come back as a train wreck, or worse end up at another practitioner’s office and they go, “Gosh, what the hell was he doing?”

We all want these eyes to remain healthy. That’s the biggest thing. “Is this lens that I’m creating for this individual going to harm them?” That’s more of what I’ve evolved into my fitting philosophy.

Dr. Sindt: Well, I think that’s a key thing with medical contact lenses—we could harm people with them.

Dr. Gelles: Yeah. Double-edged sword for sure, you have to know what is going on with the eye.

Dr. Woo: And maybe that goes back to the topic of the dabblers. Doctors with less experience have good intentions, but if you don’t know what you’re looking for, you don’t know proper follow-up care, especially for some of these very diseased corneas or people who are at risk, you could really harm someone.

Dr. Gelles: I cannot count the number of times that I’ve gotten a patient who comes into our office when just the basics of a scleral lens fit are not even close to being followed.

Dr. Miller: I still encounter some ODs who say they are doing scleral lenses, and they don’t own any sort of topographer. I find that to be wild. Who is telling you that this is okay? Because you’re clearly not managing disease processes, just the plastic itself, unless maybe you’re doing some very active comanagement system.

There’s no way you’re at the depth of knowledge that you should be if you don’t have a topographer but you’re fitting sclerals.

Dr. Arnold: Or a practitioner who only uses one lens all the time. One lens on everybody.

|

|

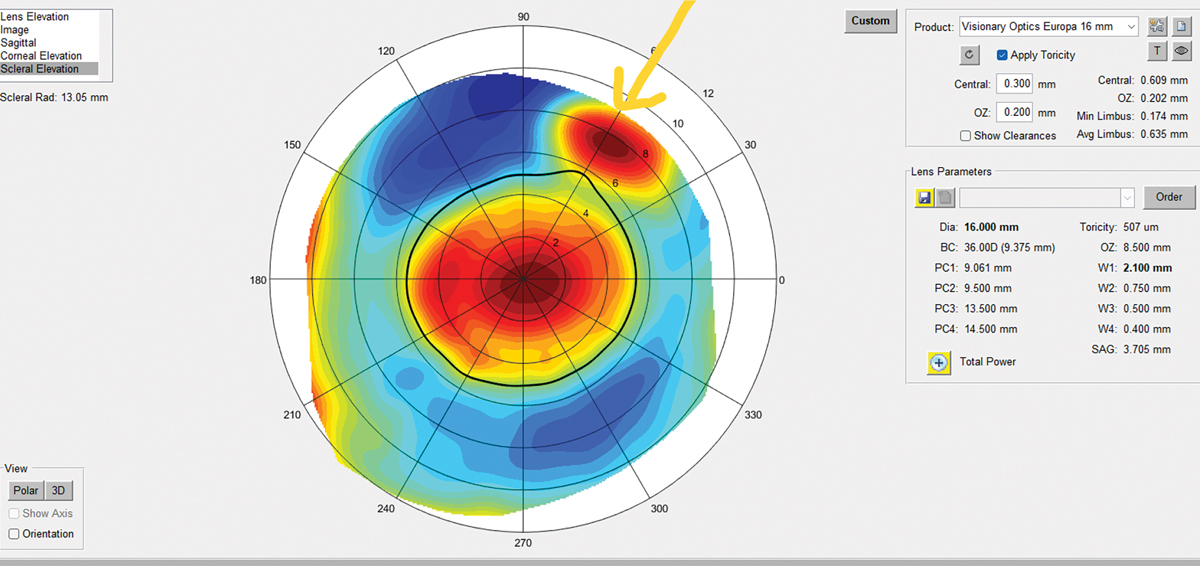

Using scleral profilometry can help clinicians create a well-designed lens that works best for the patient. Photo: Stephanie L. Woo, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Dr. Andrzejewski: Here’s the one thing that I think is always interesting about scleral lenses. I very much try to fit scleral lenses responsibly, in the sense of looking for reasons to maybe not fit a scleral on some patients.

Sure, it’s very easy to put sclerals on everybody, because they’re comfortable and you get that wow factor. But if you can get by with something else, why not? Is two weeks of GP adaptation really that bad? For some patients, yes. Others will take the time to adapt, usually for the sake of better vision. The vision with GPs can be very motivating.

If a corneal GP lens bothers a patient, what does that patient do? They usually stop wearing it. However, if a patient’s having a problem with a scleral lens, what do they do? They keep wearing it, thinking it’s going to get better. And they can rationalize it to themselves: “Oh, it just hurts when I take it off,” probably because it’s touching the cornea or squeezing the limbus. They just keep wearing it and wearing it. Then, once they’re really miserable, they come into your office. It’s so much worse because they didn’t stop wearing it. The lens size is sometimes too forgiving and doesn’t give patients the immediate feedback they sometimes need.

It’s especially hard because we know how often patients are lost to follow-up. I saw a 40-something-year- old GP wearer recently who hadn’t had an eye exam in 12 years. He had gone to another practitioner during COVID, but they didn’t fit GPs. He then came to see me asking for sclerals, telling me how he wants things easy and doesn’t want to deal with anything complicated and time-consuming. I had to have an honest discussion with the patient, telling him, “Sir, scleral lenses are definitely more complicated than corneal GPs.”

I was thinking to myself, “You haven’t had an eye exam in 12 years and were forced to finally because you went and bought lenses online that you’ve had for seven months now, and your eyes feel miserable. That’s what it took for you to come in. What are you going to do with scleral lenses? You’re going to take these lenses and run, and you might not even let me finish completing the fit because we all know it’s rarely one lens and done. Why am I going to put you in a scleral? You don’t seem trustworthy to return for follow-up.”

This anecdote underscores the importance of looking at the whole package, anatomy and psychology.

Dr. Noyes: Excellent point, Tiffany. Clearly agree with everything, just one thing that I would add is that as uses for scleral lenses, or even GPs, do tend to increase, there’s more and more stuff we’ve got to figure out. Talking to people in the field and sharing ideas in a forum like this is also a huge help. You’ve got to try and stay on top of it however you can.

Dr. Arnold: The people who have been doing this a long time, they’re so humble and talk about all their failures and how sometimes even they are confused. Like Chris told me, “Sometimes, it’s just hard.” We’re always learning, we’re always evolving—it’s an amazing time, it’s the best time in the world to be an optometrist. But challenges never go away; others just take their place.

|

|

The contact lens coordinator should complete this internal screening form as they vet the new patient prior to the initial appointment. Feel free to download this form here. Provided by Tom Arnold, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

PART III: Pearls for Post-op Lenses

Dr. Sindt: I thought this was a great conversation. Thank you, everyone. Maybe we can end with a quick look at different corneal surgeries and the approach to specialty lens choices for each, be it old radial keratotomy (RK) eyes, LASIK patients, PK vs. a lamellar graft or eyes with tube shunts. Do these factor into your approach?

Dr. Gelles: In PKs, you’re looking for swelling, you need to monitor for edema. Whether that means that you’re looking for microcysts or, more appropriately, using corneal tomography to look at your global pachymetry, you’re monitoring what their cornea is doing in response to the lens over time.

For RK, it’s all about making sure that your lens vault is up and over everything, and you’re not allowing things to be compressed or cause problems. Compression leads to neovascularization of those incisions. With tube shunts, ultimately, the answer is always EyePrint. The lens has to go over the tube shunt, and it has to not touch or compress it. If you touch or compress it, you end up with breakdown to the overlaying tissue and erosion of the tube. This can open the patient up to really, really bad things like endophthalmitis.

Resources for New Scleral Lens WearersProvided by Tom Arnold, OD Give this list of resources to patients at the initial evaluation so they can get familiar with scleral lenses—not only with indications and usage but also training videos and access to solutions. YouTube Videos: 1. youtu.be/hOdl2P6qyZU - Scleral Lens Insertion and Removal (Scleral Lens Education Society) 2. youtu.be/xHRTuDXqV7E - Patient removal—plunger method (Blanchard Contact Lenses) 3. youtu.be/K12S7Q7tol0 - Patient removal—pop out method (Blanchard Contact Lenses) 4. youtu.be/gBbrY19GpsY - Custom Stable Care and Handling (Valley Contax) 5. www.youtu.be/MKPu8cSAxII - Introduction to Scleral Lenses (Mayo Clinic) Websites: www.onefitlenses.com/handling-onefit www.allaboutvision.com/contacts/scleral-lenses.htm www.sclerallens.org/for-patients-2/patient-faqs Caring for Your Lenses: Evening Care Regimen:

A daily cleaner and Progent are not required with lenses treated with Hydra-PEG. Morning Care Regimen:

Solution Vendors: www.myeyesupply.com (scleral lens kits, rubber plungers, Unique pH, Progent and others) www.meniconamerica.com (LacriPure Saline) For Additional Lubrication: In bowl—Oasis Tears Plus Over lenses—Refresh Optive nonpreservative, Systane nonpreservative or Blink Contacts |

Dr. Arnold: One thing, going back to small vs. larger lenses, I think it’s a rule of thumb that when you’re trying to do RK, PK, all these things, you need to go to the larger lens. It’s very difficult to get up and over, and then come down. I think those particular post-surgical cases need a larger lens.

Dr. Sindt: I start at the eyelid. Are they over-bioburdened, inflammatory, are the lids positioned right and properly mobile? Am I going to be battling somebody’s rosacea on top of everything else? Do their eyelids even touch their globe or are they flapping in the breeze?

Next, I go to the cornea. Do I have a weird shape that I’m dealing with, do I have an epithelial problem, a stromal problem, an endothelial problem? Do I have pingueculae, conjunctivochalasis, granulomas, all those kinds of things?

Every one of those things is going to make me think, “How annoyed am I going to be by that?” And if I’m annoyed, that helps me decide which lens. Do I want to go big and get over it, do I want to go small and avoid it? It doesn’t matter what the surgical state of the eye is. What matters is the health situation of every single layer of that eye. Am I going to drive inflammation? And if I am, do I have to manage the inflammation first?

Dr. Gelles: Two other things. First, do you have a collaborative care team? Do you have a team in place if it goes south? And second, there’s a ton of different lenses out there. Remember that a scleral lens is not the right answer all the time. Be creative, find the right solution for the patient and go from there.

Dr. Miller: Pingueculae can especially drive me crazy. I’m just thinking of this patient right now—they were big, I was ambitious, and I probably should have just gone smaller on this person and avoided the pingueculae altogether. So, yes, I would agree with everything you said, Chris. That is the approach to take when considering sclerals vs. GPs.

Dr. Sindt: What it really comes down to is how annoying is the fit going to be to me. How much work do I have to put into it, how much follow-up care, what are the possible complications? I just want everything to work, and I can control at least some of that at the outset with the choices I make.

Dr. Arnold: You can’t rule out the patient’s personality, expectations and demands.

Dr. Gelles: I have one last pearl that I want to put in there that’s very important for your patients after crosslinking. You can put them back into their scleral lens two to four weeks post-op, right? Many have heard these absurd recommendations, like suspension of lens wear for three months. It’s not the case. We’ve been doing it for years without an issue.

Focusing on medical lenses in your practice is an investment. Managing complex scleral fits and specialty lens complications can be practiced by motivated eyecare practitioners. But don’t expect it to be easy.