|

A 63-year-old male presented to the emergency room (ER) for onset of pain experienced two days prior, starting with left ear pain that radiated over to the left temporal side of his face, including his jaw. He reported “the muscles in his eye hurt” and had pain on eye movement. He also reported his eyeball was “irritated” and had tearing.

At the ER, the patient had a CT orbit with contrast; results were unremarkable. He had no ocular history and had not received the shingles vaccine, but reported exposure to varicella-zoster infection by his grandchild. Differentials included giant cell arteritis due to the patient’s age and symptoms; however, his inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C-reactive protein) turned out to be low. Vision was 20/30 OD and OS with no afferent pupillary defect and intraocular pressures (IOPs) reading 12mm Hg OD and 13mm Hg OS. Slight erythema and early vesicle formation was seen on the lids OS.

During the ER bedside exam, an epithelial defect was reported with the posterior segment unremarkable. The patient was put on oral acyclovir 800mg five times daily, preservative-free artificial tears every hour to the left eye, erythromycin ointment to skin lesions and the left eye BID, warm compresses to periocular skin TID and cool compresses to the left eye BID. Gabapentin was also prescribed for pain and a varicella-zoster virus (VZV) IgM was ordered.

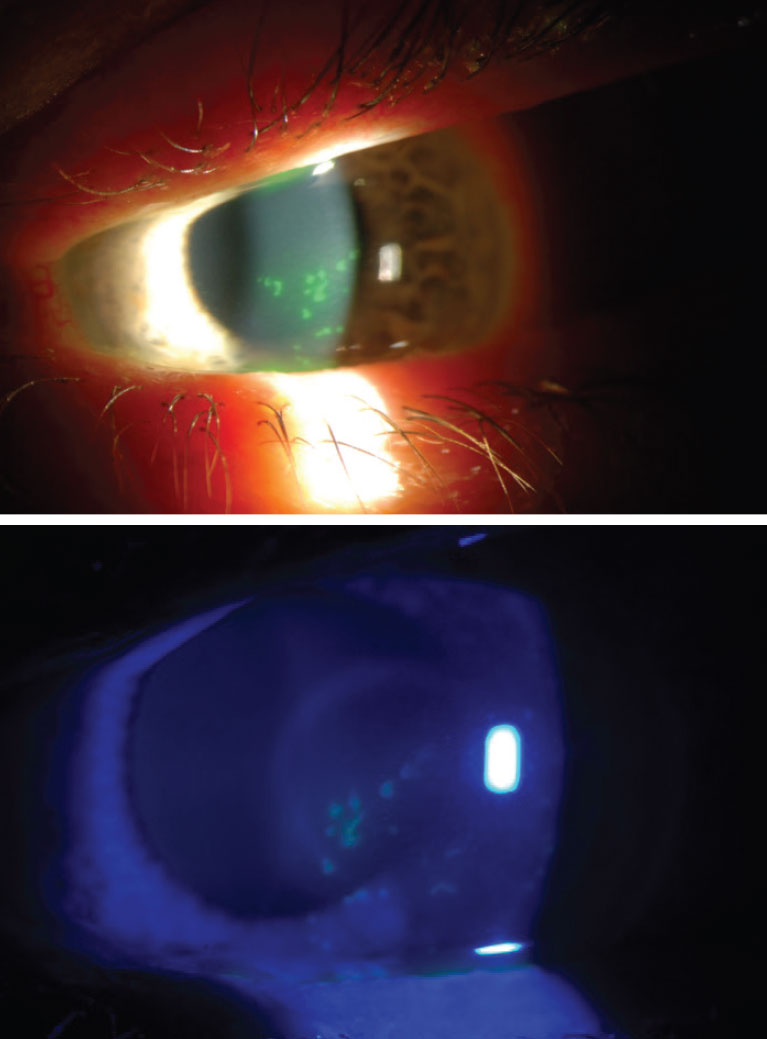

Two days later, the patient reported to our clinic. His entering uncorrected acuity was 20/20 OD and 20/50 OS with no afferent pupillary defect. At this visit, we couldn’t obtain IOP readings due to pain. The slit lamp exam revealed the patient was status post-LASIK many years ago and an inferior dendritiform lesion; the posterior segment was unremarkable to the extent seen. He continued all medications and increased his erythromycin ointment to QID.

He returned one week after his visit, reporting significant improvement of his ocular symptoms but was still suffering greatly from skin lesions. His uncorrected vision OS was 20/30 with IOP elevated to 26mm Hg. On this visit, the slit lamp exam revealed mild inferior microcystic edema and an almost resolved dendritiform lesion. A dilated fundus exam revealed no inflammation. The patient was started on timolol and prednisolone BID while also told to continue the oral acyclovir and erythromycin ointment. At the one-week follow-up visit, he was able to stop timolol, starting a slow taper of the PredForte (prednisolone acetate ophthalmic, Allergan) due to resolved herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) OS.

HZO

This is an infection from VZV commonly occurring in childhood and is usually spread by airborne, droplet or contact transmission. When a patient has a HZ infection, it is from a reactivation of the latent VZV lying dormant in the sensory nerve ganglion. Any patient that has had chickenpox is at risk for HZ development. Outbreaks often occur with weakened immunity; this is referred to as shingles. The condition usually appears unilaterally and often as a maculopapular or vascular rash along a single dermatomal distribution.

HZO, which our patient was diagnosed with, is defined as the viral involvement of the ophthalmic division (V1) of the trigeminal cranial nerve (V). The V1 is subdivided into three branches: the frontal nerve, nasociliary nerve and lacrimal nerve branches, any or all of which can be affected by HZO. Main risk factors for development include age greater than 50 and immunocompromised status.1 Our patient fit both demographics, being older and undergoing cancer treatment.

In the US, approximately one per 1,000 individuals have HZ per year; however, this rate rises closer to one per 100 those 60 years or older.2 One million new cases of HZ are reported annually, making it important to discuss with your patients that lower incidence occurs in those who had either the live attenuated or inactive recombinant zoster vaccines.2,3 In this case, the patient had not received either.

Warning Signs

Before ocular involvement, these patients often present with prodromal pain in a unilateral V1 dermatomal distribution, then with an erythematous vesicular or pustular rash in the same area. Patients often describe the sensation as burning or shooting, and occasionally, they experience fever, malaise and/or headaches before the herpetic rash. Our patient experienced the shooting sensation without other symptoms.

Another non-ocular association is Hutchinson’s sign, a rash involving the tip of the nose, which can develop from innervation of the nasociliary fibers. This sign is associated with a higher HZO risk, but around 30% of HZ patients without the sign will still develop HZO.3

Most HZ cases occur along truncal dermatomes, with only around 10% stimulating the trigeminal nerve, causing HZO.3 In cases og HZO, eye involvement is not required but is involved about 50% of the time. Most commonly, ocular manifestations include conjunctivitis, uveitis, episcleritis, keratitis and retinitis.2 Differential diagnoses for HZO are migraine, giant cell arteritis and herpes simplex virus.

Most adults already have antibodies to chickenpox and therefore will have antibodies against VZV, making serology less helpful. Diagnosis can be made by clinical presentation or a polymerase chain reaction test of the tear film, which detects the herpes virus DNA. However, this is not widely available and is expensive.

|

|

An example of herpetic keratitis. Click image to enlarge. |

Treatment

Management of HZO is not fully agreed upon. Patients are most commonly prescribed oral acyclovir tablets (either 800mg five times a day for seven days, valacyclovir 1g or famciclovir 500mg three times a day). Intravenous treatment is reserved for patients with HIV/AIDs. If this antiviral treatment is given within 72 hours of initial symptoms—specifically blisters—it is thought to reduce risk of chronic ocular complications by 20% to 30%, as well as aid in pain reduction and speeding of rash-healing time.4

If HZO involves dendritic keratitis or uveitis, chronicity should be addressed. Should this occur, one may opt to treat the cornea with topical acyclovir 3% ointment or ganciclovir 0.15% five times a day for at least five days. Most clinicians do not add topical treatment if the patient is already taking oral treatment. Steroids should be added with stromal involvement or uveitis, then slowly tapered off. Be aware that tapering prior to full inflammatory resolution can result in prolonged healing. If treated properly, it is estimated that ocular HZO complication rates decrease from 39% to 2%.3

Sequelae can range from ocular to full-body effects. Once acute signs and symptoms have resolved, keep in mind that these patients can end up developing corneal anesthesia or neurotrophic keratitis. Neurotrophic keratitis can lead to epithelial defects, infections and scarring; therefore, frequent lubrication and monitoring is essential. Increase in IOP can be caused by disease or the steroid treatment used. In severe cases, posterior segment complications, including ocular apex syndrome, optic neuritis and acute retinal necrosis, can occur.1

There is no evidence-based treatment for chronic and recurrent HZO. The most common practice pattern is to treat with a combination of oral antivirals and topical corticosteroids. Risk factors for chronic HZO include ocular hypertension and uveitis, while risk factors for recurrent HZO are female sex, an age greater than 50, immunocompromised status, more than 30 days of pain, autoimmune conditions, ocular hypertension and uveitis. The Zoster Eye Disease Study is assessing whether 1,000mg daily reduces ocular complications for chronic HZO. In the study, the researchers found that over half of respondents use prolonged antivirals for HZO treatment, with the dosage of 400mg oral acyclovir twice daily often being used.

This patient did very well with the initial oral antiviral, ocular hypertension drops and steroids; he was off all medications and scheduled for follow-up. Three to four weeks later, he returned for his follow-up, having noticed a shift in vision of one to two weeks. Any ideas what happened?

1. Liesegang TJ. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus natural history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and morbidity. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(2 Suppl):S3-12. 2. Minor M, Payne E. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Last updated August 14, 2023. 3. Tran KD, Falcone MM, Choi DS, et al. Epidemiology of herpes zoster ophthalmicus: recurrence and chronicity. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(7):1469-75. 4. Tuft S. How to manage herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Community Eye Health. 2020;33(108):71-2. |