Over the past decade or so, scleral lenses have experienced a significant surge in popularity due to their remarkable ability to enhance vision, accommodate complex ocular conditions, manage dry eye syndrome and even maintain wearer comfort. These lenses have revolutionized patient care in recent years by providing a unique opportunity for sharper, more comfortable vision.

My practice, located in Scottsdale, AZ, is dedicated exclusively to the design and fitting of specialty contact lenses. We do not conduct comprehensive eye exams, dispense eyeglasses or even fit commercially available soft contact lenses. Consequently, the majority of our patients present with complex cases, often requiring scleral lenses to address the visual issues they are experiencing. It is immensely rewarding to witness patients with advanced, challenging-to-fit ocular conditions achieve comfortable and clear vision through our efforts. Throughout my years of practice and consultation, I have encountered a plethora of scleral lens fittings. Here, I will share some common mistakes observed during the fitting process of this particular lens.

1. Selecting the Incorrect Diameter

When opting for this lens modality for a patient, the first step in fitting a scleral lens is to select the appropriate diameter. Each fitting set will have suggested values, so it is advisable to consult with your fitting consultant for your preferred lens to understand the process for determining the initial diameter needed.

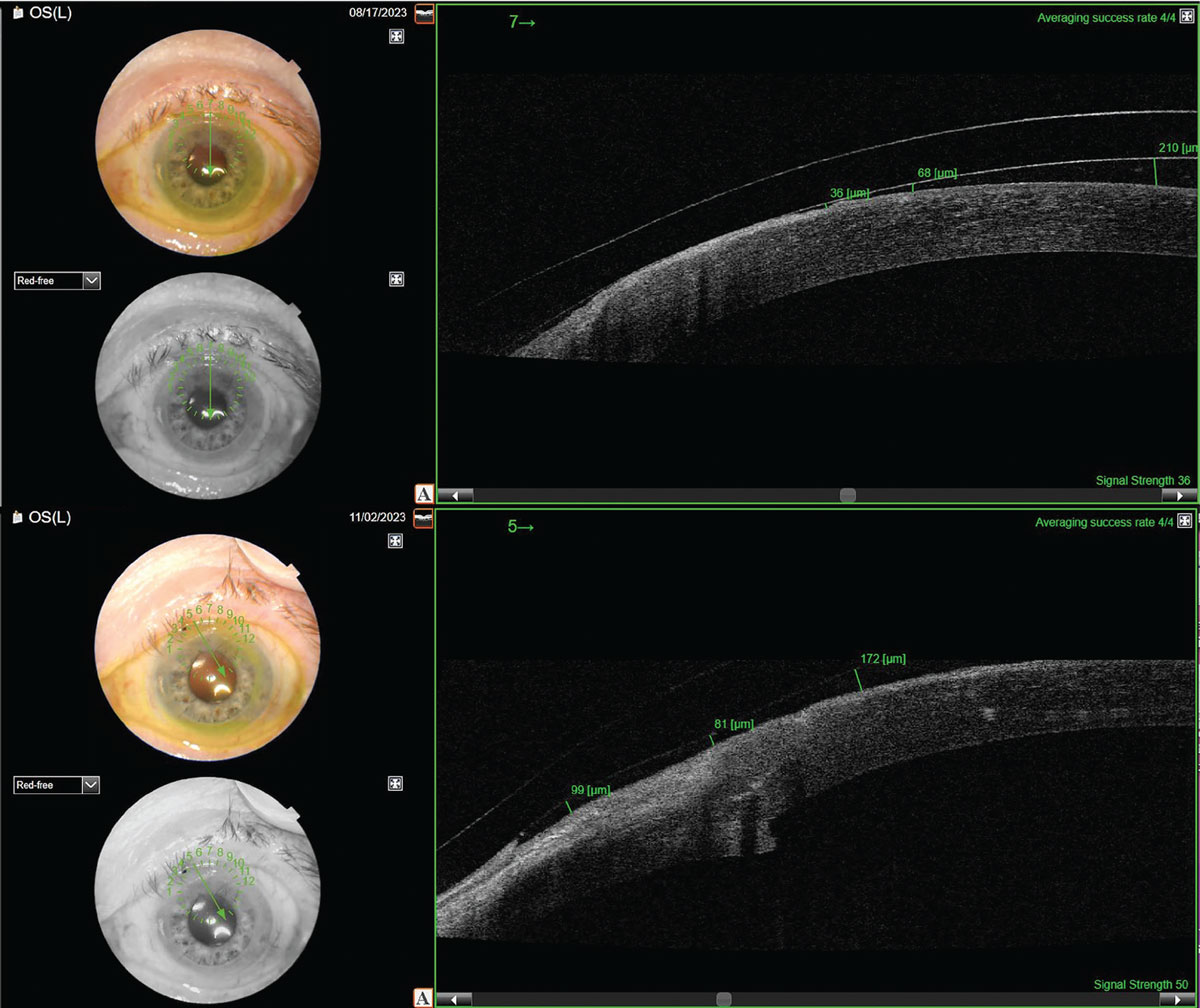

A common mistake among novice fitters is choosing lenses that are either too small or too large. If the lens is too small, it will not adequately lift off the limbus, regardless of adjustments to the limbal zone. Conversely, if the lens is too large, it will land too far from the limbus, causing the conjunctiva to be drawn under the lens resulting in sagging. This issue causes the lens to come very close to the superior limbus while having excessive vault inferiorly, which cannot be corrected simply by limbal adjustments.

Horizontal visible iris diameter (HVID) is the measurement of the horizontal width of the iris from limbus to limbus, where the cornea meets the sclera. It is typically measured using calipers on the slit lamp, digital imaging systems or specialized instruments like a keratometer or corneal topographer. You can also measure HVID with just a ruler.

The larger the HVID, the greater the depth of the anterior segment. This translates into needing larger diameter scleral lenses in order to create a larger vault to clear the cornea. Choosing a proper diameter for the lenses is the first step to ensure that the scleral lens will vault over the cornea without causing pressure or discomfort. It’s an important measurement for those with asymmetrical eyes as well as determining edge lift and clearance.

The average HVID is approximately 11.7mm to 11.8mm.1-3 For patients with this corneal diameter, a variety of lens diameters can be successful. Generally, for corneas with a diameter under 11.5mm, smaller lenses around 14mm to 15mm might work well. For corneas with a diameter of 12.1mm or greater, larger lenses, around 17mm to 18mm, are usually more suitable. It is important to note that the actual diameter may vary; this is dependent upon the specific lens design.

Understanding the differences between HVID and vertical visible iris diameter (VVID) is also essential in contact lens design—especially for specialized lenses like scleral lenses used for patients with corneal irregularities. VVID measures the vertical height of the iris from the superior to the inferior limbus. Like HVID, this measurement can be taken with various tools designed for ocular measurement, but I have found that measuring it with calipers on my OCT on the photo of the eye is the easiest for me. Like with HVID, VVID can also be measured in a slit lamp or with a ruler.

Large changes in HVID vs. VVID may indicate higher amounts of astigmatism and may require changes in the optic zone shape—such as an oval optic zone—which will change the vault horizontally vs. vertically. There are also lens designs coming out with changes to the back optic zone so that the horizontal and vertical curvatures vary and are in better alignment with the shape of the eye. This results in a lens that centers more easily and induces less fogging.

|

|

The top image depicts a lens that is much too large for the eye, causing inferior decentration and superior corneal touch. This patient felt discomfort after three to four hours of wear (the exact time the lens would have settled down to touch the cornea). The bottom image displays a smaller version of a scleral lens over the same eye. This lens is vaulting over the superior cornea and is not touching. Click image to enlarge. |

This concept is less relevant with freeform scleral lenses. Freeform lenses include such as those designed through scanning or impression techniques, as these methods allow the limbus to be defined by software rather than relying on a predetermined landing design.

If I find that there is a large difference between the eye’s HVID and VVID, I will frequently encounter the scleral lens trials in-office decentering inferiorly or inferior-temporally. In these cases, I usually recommend a freeform design or a design with some sort of back surface bi-elevation. Bi-elevation refers to the differing curves between the horizontal and vertical meridians on the back of a scleral lens. This nomenclature will differ depending on which conventional scleral lens design you are using, so I would suggest discussing with your scleral lens lab if they have this capability.

In terms of a practice management technique, I have found that my patients just want what is going to yield them the best results. If I see a trial scleral lens on the eye that decenters hugely and is a very poor fit, I recommend switching to a freeform design right away and discuss the difficulties that a conventional scleral lens fitting might present to both myself trying to fit said lenses and to the patient in wearing them.

2. Failing to Remove the Lens and Apply Fluorescein Stain

Another frequent fitting error I have observed is the provider’s omission of lens removal to stain the cornea and conjunctiva with fluorescein. By performing staining after the lens has been removed, clinicians can identify areas where the lens edges may be excessively tight, as evidenced by conjunctival staining. Additionally, this practice allows for the detection of corneal contact points and subtle regions of corneal microcystic edema.

3. Not Assessing Edge Lift with Fluorescein

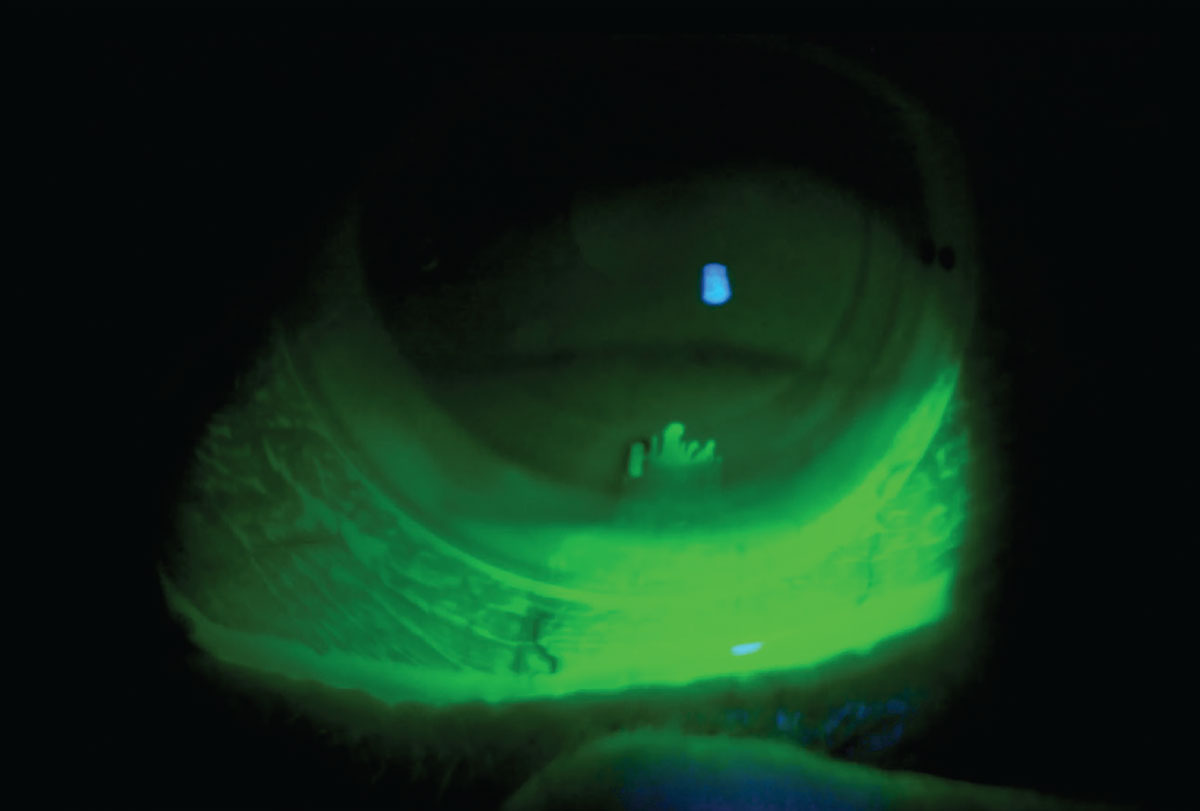

To evaluate edge lift, apply fluorescein to the superior conjunctiva over the lens and immediately examine the lens via slit lamp. Observe if and how quickly the fluorescein penetrates beneath the lens. Proper edge alignment is crucial for eliminating midday fogging, which occurs when natural tears mix with the clear saline beneath the lens. Natural tears are not as clear as the saline solution; this is due to tears’ composition, which can cause blurry vision. By identifying areas where fluorescein seeps under the lens, you can determine where to tighten the edges to reduce fogging. If no fluorescein seepage is observed and the patient reports blurry vision, consider other factors, such as prescription accuracy or the presence of corneal edema.

|

|

Here, fluorescein is put over the lens during a follow-up examination. This patient was complaining of midday fogging, but when I inserted the fluorescein initially, there was no uptake. I gently added some pressure with the lid to the bottom of the lens and fluorescein went into the lens easily. Here, I could tell that the vertical meridian of the peripheral curves needed some steepening. After this adjustment, the midday fogging decreased. Click image to enlarge. |

4. Not Asking Those Over Age 40 What They Want to Do About Reading Glasses

We’ve all forgotten to do this, right? You put the initial scleral lens in the patient’s eyes, their vision is 20/20, they’re seeing great and then they call the office saying, “I can’t read anything!” I have a sheet in my office that details the three options for all patients over the age of 40: distance lenses with readers, monovision lenses or multifocals. We will always go over their preference for reading capabilities on the first exam prior to me ordering lenses. I also reiterate this choice at their next appointment and give them a recommended reading strength that is written down.

5. Changing What Isn't Broken

You’ve heard the phrase before: If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. However, we’re all susceptible to occasionally look for problems that may not exist. I personally have many times adjusted parameters of a lens to achieve a more textbook fit, only to have the patient tell me they prefer their old lenses. When evaluating lenses, particularly those fit by other providers, it is crucial to consider the patient’s existing satisfaction. If their lenses maintain optimal eye health, clear the cornea and offer good vision and comfort, there is no need for significant changes. Adjusting central clearance from 275µm to 200µm, for instance, is often unnecessary. Exceptions to this rule include cases where the patient experiences issues such as fogging, corneal edema or discomfort, or if they have a low endothelial cell count, in which case, lower clearances and lens thickness may enhance long-term eye health.

Takeaways

Scleral lenses are so gratifying to fit and I think the real skill in designing great fitting lenses for patients lies in fixing potential complications before they arise. I also think discussing with patients why you are choosing certain designs over others based on their anatomy is a great way to develop a following of patients who trust you and your decisions. With each lens you fit, your skill level will increase. I am 10 years in and I still keep a spreadsheet with my designs and unique things I’ve done to fix complications. You start seeing patterns when you do this enough, and that’s when you can order lenses based on the pattern you expect to see develop. This shortens the fitting process and increases patient satisfaction with their lenses. Don’t be afraid to take the plunge in starting to fit these versatile lenses!

Dr. Morrison, FAAO, FSLS, is the owner of In Focus: Specialty Contact Lens & Vision Solutions, a private practice in Scottsdale, AZ, that specializes in contact lenses for advanced ocular conditions and comprehensive care for difficult visual cases. After graduating from the New England College of Optometry, Dr. Morrison completed a Cornea & Contact Lens Residency at SUNY College of Optometry. She is the recipient of both the Bert C. and Lydia M. Corwin Contact Lens Residency Award and the Johnson & Johnson Award for Excellence in Contact Lens patient care. Prior to moving back to AZ, Dr. Morrison worked in the cornea department of New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai specializing in corneal diseases and complications. She is inspired by her patients who have overcome many visual obstacles and are motivated to regain quality vision.

1. Fogla R, Sahay P, Sharma N. Preferred practice pattern and observed outcome of deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty—a survey of Indian corneal surgeons. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69(6):1553-8. 2. Xu L, Yang K, Zhu M, et al. Trio-based exome sequencing broadens the genetic spectrum in keratoconus. Exp Eye Res. 2023;226:109342. 3. Shen L, Melles RB, Metlapally R, et al. The association of refractive error with glaucoma in a multiethnic population. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(1):92-101. |