With a dual focus on both medical and refractive eye care, optometrists are uniquely positioned to provide patient-specific vision solutions to each and every patient. While ODs are successfully meeting the needs of most patient populations, many continue to under-deliver for those patients in need of presbyopic contact lens correction.

Not a day goes by without a presbyopic patient in my chair telling me they have either tried and failed or never even pursued contact lenses because they thought they were a poor candidate. They list any number of perceived complications such as too much astigmatism, a too high or too low prescription, or dry eye, to name a few.

These patients represent a tremendous opportunity for us to look beyond the soft lens fitting sets in our offices to find a customized and highly satisfying vision solution: gas permeable (GP) multifocal lenses.

Multifocal GP lenses are available in three modalities: corneal, hybrid and scleral lenses. While each provides its own unique advantages and disadvantages, two key concepts, translation and simultaneous vision, are fundamental to multifocal GP lenses. Let’s take a look at the mechanics behind these lenses, and the variety of multifocal designs available today.

|

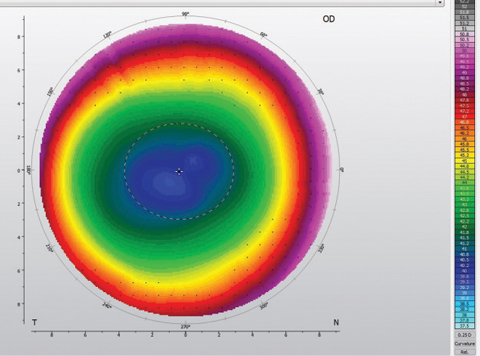

| Fig. 1. The topography of a center-distance aspheric corneal GP shows the increasing power gradient from center to periphery. |

Translation

The physical movement of a lens on the eye allows gaze-specific positioning of a desired optical portion of the lens in front of the pupil. A translating design, used for bifocal or trifocal corneal GP lenses, is a segmented corneal lens with the top of the lens containing the distance prescription and the bottom containing the reading addition. A correctly fit lens positions the distance correction in front of the pupil on primary gaze with the segment resting at or just below the inferior pupil margin, providing the patient access to the add in downgaze. These designs are only available in corneal GP lenses, as other modalities have inadequate movement.

Advantages include crisp, dedicated distance and near optics. Candidates for this type of lens are those unwilling to compromise distance visual acuity or those who have highly precise near vision requirements. This mode of correction comes with the caveat that range of vision will be compromised, as the patient is typically limited to two focal distances. Also, gaze positioning is critical: patients expecting to see near objects at or near primary gaze or overhead will not be successful with this design.

Lid anatomy is another essential factor with translating designs. Ideally, the upper lid will be positioned near or above the superior limbus with the lower lid 1mm to 2mm above the inferior limbus. This upper lid position discourages lid attachment, which can inadvertently pull the bifocal segment too high in primary gaze. The high lower lid provides the necessary ledge to position the inferior edge of the lens against. To exploit this relationship, most translating designs have a truncated lower edge, creating a flat inferior lens surface to rest against the flat inferior lid margin, further aiding in stability in primary gaze and translation in downgaze. These designs should be avoided in patients whose inferior eyelid is positioned below the inferior limbus.

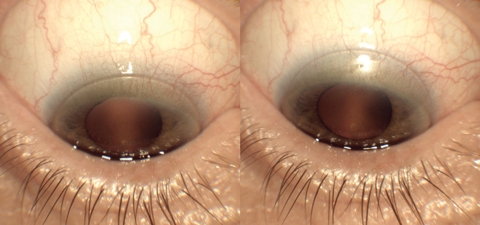

Because translation and lens positioning on the eye are key, a diagnostic fitting is integral to success with bifocal lens designs. Important fitting characteristics include an inferior to inferior-central lens position with the lower edge resting on the inferior eyelid, segment height at or slightly below the pupil margin, fast lens movement with each blink that quickly re-settles so as to not impact distance vision and at least 2mm of translation on downgaze. Because of their thickness and positioning on the eye, these lenses tend to create more initial lens awareness. This, combined with limited focal distances, render translating designs a niche lens modality.

|

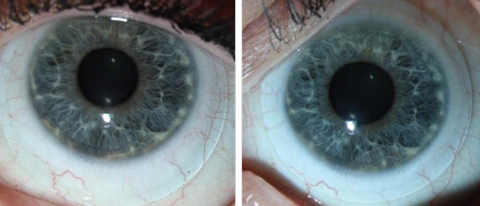

| Fig. 2. These images show the difference between inadequate translation, at left, and proper translation, at right. |

Simultaneous Vision

These lenses position distance and near optics in front of the pupil at the same time—the same design as soft multifocal lenses.

Concentric. Distinct distance and near rings are used to create a simultaneous vision correction with this design. The central portion of the lens is typically dedicated to distance vision with alternating rings of near and distance power moving from the center to the periphery of the lens. These lenses are less commonly used today due to advances in aspheric lenses.

Aspheric. This lens design uses gradual curvature changes within the optic zone to create a power gradient. The resultant optic zone contains distance, intermediate and near optics, providing patients with variable vision demands with access to the right correction for the right distance. Aspheric lenses commonly employ a center-distance zone that gradually increases in power to a near peripheral zone (Figure 1). Although this is typical, many designs are available in center-near as well, allowing flexibility and customization for each patient.

The aspheric curvature can be placed on the front or back surface of the lens. Originally, back surface aspheric lenses were used more frequently, as they employ a highly steep central curvature and provide an opportunity for significant central plus power. Although this helps clinicians attain high reading additions, the fitting relationship can cause corneal molding and resultant spectacle blur.

In contrast, when the aspheric curve is placed on the front surface of the lens, the back surface of the lens can remain spherical. This provides an easy-to-fit lens that behaves similarly to a standard spherical back surface lens when on the eye. Although higher add powers are achievable with today’s front surface designs, the more advanced presbyope may still struggle to reach their full add requirement with front aspheric optics alone. In this situation, combining front and back surface aspheric optics or binocular strategies such as over-plussing the non-dominant eye can provide more reading power.

Aspheric designs are ideal for the emerging presbyope, the patient with matching refractive and corneal astigmatism, as well as the successfully fit single-vision GP patient who is ready to transition into multifocal lenses. In the latter case, an aspheric front surface may be added to the patient’s habitual well-fitting spherical lens, allowing for a simple transition and fitting process. Factors to consider in patient selection for aspheric corneal lenses are patients seeking regular or full-time daily wear and a superior lid positioned 1mm to 2mm below the superior limbus to encourage a comfortable, lid-attached, well-positioned lens. For those who do not satisfy the above requirements, consider hybrid or scleral aspheric lenses, as they operate essentially independent of lid position and can be more comfortable for those who only wear lenses occasionally.

While aspheric lenses employ simultaneous optics, corneal aspheric lenses have the added benefit of translation, allowing for controlled positioning of near add power when reading. For center-distance corneal aspheric lenses, the properly fit lens shifts up as the patient looks down to read, positioning the pupil into the periphery of the lens. This helps the patient reach the portion of the lens that contains their full reading prescription (Figure 2). In addition, this principle allows a larger central portion of the lens to be dedicated to distance vision, maintaining crisp distance vision and reducing the inherent issues of simultaneous multifocal optics such as reduced distance contrast, glare and halos. In higher add powers, or lens designs incapable of translation, center-near optics may be employed due to the natural miosis associated with near tasks. Center-near designs will often positively impact near visual acuity at the expense of decreased distance visual acuity or increased distance symptoms of glare and halos.

|

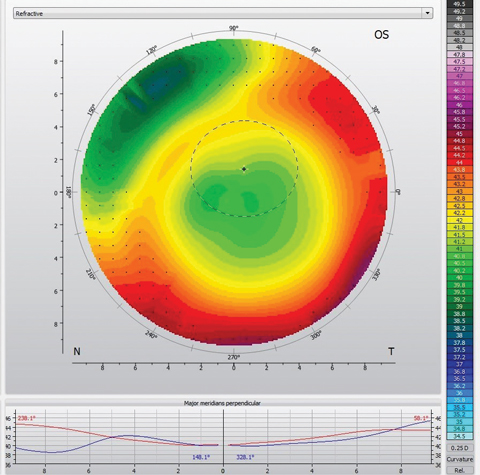

| Fig. 3. The topography of this center-distance scleral lens demonstrates inferior-temporal decentration. Note the high degree of varying power in front of the pupil (dotted black circle). |

Modalities

The three GP multifocal lens modalities currently available—corneal, hybrid and scleral—each have their own unique properties that make them ideal for different patients:

Corneal GP lenses are available in translating, concentric and aspheric lens designs. As with single vision corneal GP lenses, multifocal corneal GP lenses benefit from nearly endless customization for both fit and optics. Parameters include a wide range of distance prescriptions and add powers in 0.25D increments or smaller. In addition, many designs are available with variable center-distance or near zones.

The overwhelming visual advantage of corneal GPs is their on-eye movement. Movement provides not only translation, but also pumps tears under the lens, providing hydration to the cornea and improved oxygen availability. Despite these advantages, movement also contributes to an increased initial lens awareness, creating a longer adaptation period.

Factors to consider in patient selection are refraction, wear schedule and vision demands. Corneal GP multifocals allow for the correction of both corneal and residual astigmatism, making them a great option for patients whose corneal and refractive astigmatism do not correspond. Patients who commonly find success with lens adaptation and comfort are those who wear their contact lenses as their primary vision correction. Finally, corneal lenses may be the best option for those with high vision demands at both distance and near due to their ability to translate.

Hybrid lenses, with their GP center and soft skirt, can provide patients with the best of both worlds. GP optics are often superior to their soft lens counterparts and allow for the correction of corneal astigmatism. The skirt provides improved initial comfort compared with corneal GP lenses and helps center the optics over the pupil. This centration is key, as the currently available multifocal hybrid lens options are center-near aspheric designs.

The disadvantages of a hybrid lens include limited physical and optical customization, a lack of translation and handling difficulties. Only one diameter is available, so patients who vary significantly from standard horizontal visible iris diameter (less than 11.6mm or more than 12.0mm in my practice) may struggle to achieve a healthy and comfortable fit. In addition, limited add power options and an inability to alter the size of near and distance zones hinders the customization some patients require. A complete reliance on simultaneous vision with a lack of translation may also decrease the overall clarity of vision compared with corneal GPs. With these lenses, patients may note difficulty with removal, as a specific inferiorly positioned and close finger pinch technique with dry fingers is required to remove the lens.

With their ability to address corneal astigmatism, hybrid lenses can offer presbyopic patients improved clarity compared with soft lenses, in addition to less initial lens awareness than corneal GP lenses.

Scleral lens designs, due to their lack of movement on the eye, employ simultaneous vision. The properly fit scleral lens moves minimally, if at all, on the eye, distributes its weight on the relatively insensitive conjunctiva and provides nearly no edge awareness—adding up to a highly comfortable lens with minimal initial lens awareness.

Depending on the specific design, center-near, center-distance or both are usually available. Some designs take advantage of the binocular system by matching the dominant eye with center-distance and non-dominant eye with center-near, or employ larger or smaller distance and near zones in the dominant and non-dominant eye. As with corneal GPs, customization abounds for most designs with add powers ranging from +1.25D to more than +3.00D—many available in 0.25D steps—and variable center-near and -distance zones to account for pupil size variation.

Many of the commonly fit scleral lens designs are now available with multifocal optics, and clinicians can fit the patient from their existing diagnostic fitting set. When placing the order, simply incorporate the multifocal optics, commonly based on a combination of add power, eye dominance and pupil size.

Scleral lenses can help clinicians address vision and comfort, both of which are key contributing factors to the increased contact lens dropout rate in patients older than age 45.1-3 The post-lens tear reservoir of a scleral lens can be advantageous when addressing both vision and comfort, whether neutralizing irregular or regular corneal astigmatism, providing relief for ocular surface dryness or, more commonly, a combination of all three.

Neutralizing corneal astigmatism may improve the clarity of vision in presbyopic patients with matching corneal and refractive astigmatism. This, combined with precise add customization and the ability to match pupil size with distance/add zones, provides scleral lenses a distinct advantage over soft multifocal lenses for some patients.

In addition, scleral lenses can be exceptionally comfortable. The tear reservoir also helps to provide constant hydration to the corneal surface—a great feature for patients experiencing dry eye or those who could be pushed into a symptomatic state with contact lens wear.

|

| Fig. 4. These images show an inferiorly decentered scleral lens, at left, vs. a well-centered scleral lens, at right. This improvement in centration was accomplished by decreasing the diameter of the lens. |

Although an excellent option for many, patients unwilling to compromise their distance or near vision may be more successful in corneal GP designs that allow for translation. Some patients may struggle with insertion and removal of scleral lenses, and all patients should be well educated upfront on the particular handling requirements. Finally, patients with endothelial cell dysfunction or those who demand exceptionally long wear schedules (exceeding 16 hours a day of lens wear) are typically better served in corneal lens designs due to the relatively decreased oxygen availability of scleral lenses.

Multifocal scleral lenses are fit with the same philosophy as other indications for scleral lens wear. One common obstacle in fitting multifocal sclerals can be centration. We know that scleral lenses typically decenter inferior and temporal, which, combined with the natural tendency of the pupil to be minimally decentered superior and nasal, results in a mismatch (Figure 3). Clinicians should employ every strategy to improve centration, including adding toric or quadrant specific haptics, decreasing lens thickness, minimizing central and limbal clearance and decreasing diameter (Figure 4).

Where to start?

When a presbyopic patient is interested in multifocal contact lenses, you should begin with what you know and are comfortable fitting. For the majority of multifocal lens designs, the physical characteristics that lead to success are comparable with their single vision counterparts. If you are already comfortable with corneal GPs, start with a front aspheric design, which can be easier to fit with its spherical back surface. If you are happy with hybrids, impress a patient with matching refractive and corneal astigmatism with the sharpness they were never able to achieve with their soft multifocals. If scleral lenses are your new passion, fit the patient similarly to your other scleral lens patients (focusing on centration) and then dial in the multifocal optics.

With an understanding of GP multifocal basics and the drive to help your patients find their clearest and most comfortable vision correction, you are on your way to broader multifocal lens fitting success.

Dr. Collier is a partner at Artisan Eye in Lakewood Ranch, Florida. Prior to opening Artisan Eye, he practiced at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, where he focused on specialty contact lenses for refractive and therapeutic patients. He is a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry and the Scleral Lens Education Society.

1. Richdale K, Sinnott LT, Skadahl E, Nichols JJ. Frequency of and factors associated with contact lens dissatisfaction and discontinuation. Cornea. 2007;26(2):168-74. |