Eye makeup has long been used to enhance personal appearance, to improve self-esteem or attract the attention of others. For Egyptians, who considered the eyes to be the window of the spirit, kohl—heavily laced with lead—and green malachite were used for decoration, as protection against eye ailments and for darkening sun protection. While chemistry has improved and products today have a considerably greater safety profile, eye makeup-related ocular problems are not uncommon—yet, they are often overlooked in everyday clinical practice. One reason may simply be lack of awareness as to the role that makeup products can play in allergic contact dermatitis, meibomian gland dysfunction, infection, dry eye and trauma.

Surprisingly, 49% of all allergic reactions occur in the eye or face region.1 In a large multi-center study of cosmetic reactions, Robert Adams, M.D., and Howard Maibach, M.D., found that both the patient and the observing physician had a low level of awareness about the cause and effect between a cosmetic and the subsequent reaction.2 A two-year study of 532 patients with a known cosmetic related allergy found that 7.5% of the participants had a positive reaction to their own products, with another 15.4% having doubtfully positive reactions.3 Roughly a quarter of our patients are using makeup that is causing an adverse reaction and not realizing it. Therefore, it is important to thoroughly investigate makeup products and usage habits when a patient presents with eyelid dermatitis, epiphora, irritation, conjunctivitis or infection.

Understanding the Market

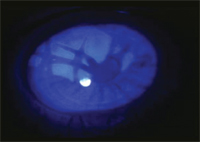

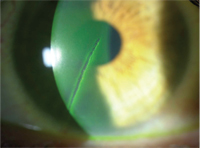

Corneal burn from heated eyelash curler.

As of 2005, the global cosmetics and toiletries market equaled 155 billion dollars.4 Mascara alone—whether used to lengthen, thicken or darken the appearance of eyelashes—accounts globally for $3.7 billion annually.5 Ingredients, preservatives, dyes and fragrances in commonly used makeup products—mascara, eye shadow, eyeliner and eye makeup remover solutions—are often implicated in allergic contact dermatitis.6 Yet, despite their widespread use, these products are classified as non-prescription items and, therefore, are not regulated by the FDA. Only the use of color additives, such as kohl for eyelash and eyebrow tinting, is prohibited. For color addictives, the manufacturers are required to have an ingredient declaration, but often, each ingredient contains myriad components that are impractical and optional to list. This quagmire makes it virtually impossible to isolate the offending allergen. Instead, it is left to the individual manufacturers to self-police and report post-marketing adverse events under the Voluntary Cosmetic Registration Program.7

The FDA does define which preservatives can be used in makeup. However, these approved preservatives start to break down with air exposure and repeated use; potential bacterial and fungal contamination can later cause serious ocular infections. For products that are packaged in a tube where the applicator is withdrawn and reinserted continually—such as eyeshadow or mascara—there is increased risk of contamination and, therefore, patients should be advised to replace these products every three months.

Makeup Etiquette Revisited

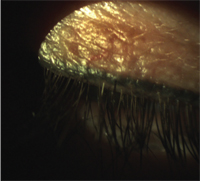

Permanent eyelid tattooing.

Women may unwittingly be self-inflicting problems by failing to remove their makeup daily. Another common problem is the sharing of makeup. We often share products with friends and family members and don’t think twice before sampling products at specialty, department or drug stores prior to purchase. Studies have shown that this shared use leaves cosmetics swarming with bacteria—such as Staphylococcus aureus and epidermis, micrococcus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and fungus. One study collected 3,027 samples of eye, face and skin makeup from 171 retail stores across the United States. Bacteria was isolated from approximately 49% of the 1,505 eye samples, with an estimated 5% carrying microbial loads considered unacceptable under current guidelines.8 Elizabeth Brooks, Ph.D., of Rowan University, conducted a two-year, double-blind study on samples collected from 20 companies at department store makeup counters. Testing showed a 67% to 100% bacterial contamination in the samples, notably Staph, Strep and even E. Coli bacteria.9 The risk of infection is further enhanced if there is any trauma, corneal disease, a history of previous ocular surgery, contact lens wear, dry eyes or poor lid function.

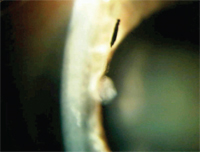

Another concern is the application of eyeliner or eye shadow on the inner eyelid margins which can cause blockage of the meibomian glands—ultimately leading to hordeolum and/or chalazian formation, dry eye and ocular irritation. Patients may be using products that contain ingredients, preservatives, dyes or fragrances that can cause contact allergic dermatitis.2 Indeed, contact dermatitis from mascara has been linked to its various ingredients—including prime yellow carnauba wax, coathylene, black iron oxide, colophony, nickel dihydroabietyl alcohol and shellac.10-17 The metals found in the pigments used for eye shadows—nickel, cobalt, lead, chromium and arsenic—also cause allergic contact dermatitis.16

Heavy use of mascara also maybe implicated as the cause of conjunctival pigmentation in patients who wear rigid gas-permeable lenses.18 It was hypothesized that poor tear exchange, and 3:00 and 9:00 o’clock staining, may compromise the conjunctival epithelium and prevent the removal of the pigment particles, allowing them to become embedded in the epithelium. Joseph Ciolino, M.D., and colleagues describe three cases of ocular pathology secondary to longterm mascara use: two patients had multiple pigmented conjunctival lesions, while one patient had a history of melanoma of the hand.19 In both cases, a biopsy revealed nonmelanocytic pigment granules within conjunctival stroma cells. The third patient had canalicular obstruction from a mascara-laden dacryolith, a concretion within the nasolacrimal system. Pseudomonas corneal ulcer also has been reported after a minor corneal abrasion with a contaminated mascara applicator.20

As practitioners, we are familiar with the corneal abrasions induced by an errant mascara brush. However, we may be less informed about other common dangers: the practice of using a straight pin, paper clip or toothpick to separate lashes and remove mascara clumping and the potential hazards of an eyelash curler—whether it be contact dermatitis from the thiuram in the rubber mechanism, an eyelid burn from a heated curler or a penetrating, open globe injury from a broken curler.21-23

Understanding Permanent Makeup

Allergic contact dermatitis.

Permanent tattooing of the eyelids, eyelashes and eyebrows is becoming an increasingly popular alternative to daily makeup application for women looking for convenient, longer lasting, simpler and less irritating beauty regimens. However, these options can cause serious complications. Therefore, the eye care practitioner needs to be aware of this phenomenon and the associated potentially adverse ocular effects in case patients inquire about, or have already undergone, the procedure.

Blepharopigmentation—the application of iron oxide pigment along the lash line by a rotary needle—was first described in 1984 as a procedure used for the purpose of eyelash enhancement and, later, the tattooing of the eyebrows.24 The FDA does not regulate the tattoo industry—or the inks or dyes utilized. With no standards in place for education or licensing, this allows openings for poorly trained technicians to perform the procedure.

Permanent makeup application carries risks of infection, allergy, fanning and fading.25 Fanning refers to the spread of the ink pattern over time because the ink was injected too deeply during application. It has been noted that granulomas can occur at the injection site, which can persist and become a chronic source of inflammation.26 Dermatitis due to the iron oxide pigment can be another complication.27 Patients at risk for keloids or individuals that have a known allergy to iron oxide containing materials should avoid the process altogether.

Monya De, M.D., and colleagues describe the case of a patient who presented with a full thickness eyelid penetration and tattooing of the conjunctiva one day following blepharopigmentation by a cosmetology student.28 There have also been isolated reports of patients experiencing transient swelling in the regions of their tattoo at or around the time of an MRI, because iron oxide may be a component of the radiocontrast material used.29 Furthermore, there can even be issues associated with ink removal. Techniques for removal include surgical excision, scraping, injection of tannic acid, or treatment with argon or pulsed carbon dioxide lasers.30 Even with the carbon dioxide laser, there is the risk of scarring and disruption of the lid anatomy.

In a phone survey with 92 patients who reported adverse events to the FDA after permanent makeup application, the most commonly reported reactions were tenderness (95%), swelling (91%), itching (88%) and bumps (83%).31 Sixty-eight percent or 63 patients reported that their reactions had not resolved; the duration of the symptoms ranged from 5.5 months to over three years.32 Patients with a self-reported history of allergy took longer to heal.

Dyes, Lash Enhancers and Fragrances

Mascara shard in the epithelium.

Adverse events from eyelash and eyebrow dyes have also been documented. Irreversible conjunctival and corneal argyrosis have been described as problems stemming from silver deposits during the self-application of eyelash tints.33 Contact dermatitis and conjunctivitis have been linked to para-phenylenediamine, a potent allergen found in hair dye.34 Igor Kaiserman, M.D., M.Sc., M.P.A., reported the case of a 38-year-old female who presented with severe allergic blepharoconjunctivitis one day after dyeing her eyebrows and eyelashes at a beauty salon; she responded to a five-day treatment of dexamethasone 0.1% and lubrication.35

Other eyelash enhancing products can also cause ocular irritation. Forty-three percent of patients using Lumigan (bimatopost 0.03%, Allergan) to reduce intraocular pressure presented with hypotrichiasis.36 In December 2008, Latisse—with the same formulation as Lumigan—was approved by the FDA for the treatment of hypotrichiasis, an inadequate amount of eyelashes.37 In a multi-center, double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled study of 278 subjects, there was a 25% increase in eyelash length, 106% increase in thickness and 18% increase in darkening in week 16.38 However, less common side effects included conjunctival hyperemia in 3.6% of subjects compared to no cases reported with the receiving vehicle and a few post-marketing reports of brown iris pigmentation.39 Interested patients should be made aware of these potential side effects and that their lashes will be affected only while they’re using the drug. There are also several unproven and unregulated over-the-counter options that claim to offer similar effects.

Drs. Adams and Maibach found that fragrance and fragrance ingredients, followed by preservatives, were the primary causes of allergic contact dermatitis in 713 patients with cosmetic-related reactions.2 Subjective complaints included burning, stinging, itching and irritation. While fragrance serves no purpose other than to provide a pleasant scent, preservatives are necessary to guard against bacterial invasion and limit degradation.

The consumer should be wary of products that claim to be “preservative-free.” Additionally, patients should be reminded that although many products use the term “hypoallergenic,” there are no regulations or standards for the use of this term. Hypoallergenic merely suggests that a product is less likely than another, similar product to cause an allergic reaction; however, manufacturers are not required to prove this claim.

Another common misnomer is the claim that a product is “fragrance- free.” Pamela Scheinman, M.D., reports on a patient who was patch test positive to multiple fragrance chemicals, including rose oil, in her fragrance free soap.40 The same is true of “natural” products, such as tea tree oil.41

Additional Concerns for CL Wearers

Corneal abrasion from a safety pin.

Contact lens wear and eye makeup usage presents its own set of challenges to the patient and practitioner; as a result, these patients are more likely to ask questions regarding proper makeup, usage and removal. We should advise patients to insert their lenses first, and then apply their makeup, to avoid transfer of any residue from their fingers onto the surface of the lens. It should be recommended that these patients use matte finish powder or cream eye shadows, rather than pearlescent or iridescent shadows which can flake off and lodge onto or under the contact lens. Extended wear patients should be advised to use water-based mascaras that are easier to remove and won’t leave an oily residue. Waterproof mascaras are not water-soluble and will not be broken done by tears and flushed away, potentially causing prolonged irritation and a possible corneal abrasion.

Treating Makeup-Related Ocular Problems

Eyelid allergic contact dermatitis is treated with palliative care, such as cool compresses and over-the-counter antihistamines; some cases may need a short course of steroid ointment. Discussion of the causative agent is critical to avoid future episodes. A detailed case history includes the type of makeup used on and around the eyes, the method and products used for makeup application and removal, and any recent permanent cosmetic tattooing.

Problems with eye makeup and cosmetic-related products are surprisingly common, though with a low risk of serious complications. Awareness, education and documentation of product types, use and related ocular adverse events can help the practitioner pinpoint where the problem may have originated and guide the proper treatment.

Dr. Chaglasian is an associate professor at the Illinois College of Optometry in Chicago and an associate at Mack Eye Center in Hoffman Estates, Ill.

Dr. Russell practices at the Marietta Eye Clinic in Marietta, Ga. He is a fellow and diplomate in Cornea and Contact Lens for the American Academy of Optometry.

1. Draelos ZK. Eye cosmetics. Dermatol Clin. 1991 Jan;9(1):1-7.

2. Adams RM, Maibach HI. A five-year study of cosmetic reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985 Dec;13(6):1062-9.

3. Held E, Johansen JD, Agner T, Menne T. Contact allergy to cosmetics: testing with patients’ own products. Contact Dermatitis, 1999 Jun;40(6):310-5.

4. Developing markets still head growth in global cosmetics and toiletries market. 2005 Jul. Available at:

www.cosmeticsdesign.com/Products-Markets/Developing-markets-still-head-growth-in-global-cosmetics-and-toiletries-market (Accessed February 2011).

5. Thomson Financial News. Allergan to file NDA for bimatoprost for stimulating eyelash growth. 2008 Jun. Available at:

www.forbes.com/feeds/afx/2008/06/04/afx5078187.html (Accessed February 2011).

6. Goosens A, Bruze M, Gruvberger B, et al. Contact allergy to sodium cocoamphoacetate present in an eye make-up remover. Contact Dermatitis. 2006 Nov;55(5):302-4.

7. FDA. Voluntary Cosmetic Registration Program (CVRP). 2010 Aug. Available at:

www.fda.gov/Cosmetics/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/VoluntaryCosmeticsRegistrationProgramVCRP/default.htm (Accessed February 2011).

8. Mislivec PB, Bandler R, Allen G. Incidence of fungi in shared-use cosmetics available to the public. J AOAC Int. 1993 Mar-Apr;76(2):430-6.

9. Tran TT, Hitchens AD. Microbiological survey of shared-use cosmetic test kits available to the public. J Ind Microbiol.1994;13:389-91.

10. Chowdhury MM. Allergic contact dermatitis from prime carnauba wax and coathylene in mascara. Contact Dermatitis. 2002 Apr;46(4):244.

11. Saxena M, Warshaw E, Ahmed DD. Eyelid allergic dermatitis to black iron oxide. Am J Contact Dermatitis. 2001 Mar;12(1):38-9.

12. Karlberg AT, Lidén C, Ehrin E. Colophony in mascara as a cause of eyelid dermatitis; chemical analyses and patch testing. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 1991;71(5):445-7.

13. Fisher AA. Allergic contact dermatitis due to rosin (colophony) in eyeshadow and mascara. Cutis. 1988 Dec;42(6):507-8.

14. Dooms-Goosens A, Degreef H, Luytens E. Dihydroabietyl alcohol (Abitol); a sensitizer in mascara. Contact Dermatitis. 1979 Dec;5(6):350-3.

15. Shaw T, Oostman H, Raney D, Storrs F. A rare eyelid dermatitis allergen: shellac in a popular mascara. Dermatitis. 2009 Dec;20(6):341-5.

16. Le Coz CJ, Leclere JM, Arnoult E, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from shellac in mascara. Contact Dermatitis. 2002 Mar;46(3):149-52

17. Sainio EL, Jolanki R, Hakala E, Kanerva L. Metals and arsenic in eye shadows. Contact Dermatitis, 2000 Jan;42(1):5-10.

18. Davis LJ, Paragina S, Kincaid MC. Mascara pigmentation of the bulbar conjunctiva associated with rigid gas permeable lens wear. Optom Vis Sci. 1992 Jan;69(1):66-71.

19. Ciolino JB, Mills DM, Meyer DR. Ocular manifestations of long-term mascara use. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009 Jul-Aug;25(4):339-41.

20. Reid FR, Wood TO. Pseudomonas corneal ulcer. The causative role of contaminated eye cosmetics. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979 Sep;97(9):1640-1.

21. Wilson SE, Bannan RA, McDonald MB, Kaufman HE. Corneal trauma and infection caused by manipulation of the eyelashes after application of mascara. Cornea. 1990 Apr;9(2):181-2.

22. Rietscel RL, Warshaw EM, Sasseville D, et al. Common contact allergens associated with eyelid dermatitis: data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group 2003-2004 study period. Dermatitis. 2007 Jun;18(2):78-81.

23. Ramasamy B, Armstrong S. Penetrating eye injury caused by eyelash curlers-a cause for concern? Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010 Mar;248(3):301-3.

24. Angres GG. Eye-liner implants: A new cosmetic procedure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984 May;73(5):833-6.

254. De Cuyper C. Permanent makeup: indications and complications. Clin Dermatol. 2008 Jan-Feb;26(1):30-4.

26. Vagefi MR, Dragan LD, Hughes SM, et al. Adverse reactions to permanent eyeliner tattoo. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006 Jan-Feb;22(1):48-51.

27. Rubianes EL, Sanchez JL. Granulomatous dermatitis to iron oxide after permanent pigmentation of the eyebrows. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1993 Jan;19(1):14-6.

28. De M, Marshak H, Uzcategui N, Chang E. Full-thickness eyelid penetration during cosmetic blepharopigmentation causing eye injury. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2008 Mar;7(1):35-8.

29. Tope WD, Shellock FG. Magnetic resonance imaging and permanent cosmetics (tattoos): survey of complications and adverse events. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002 Feb;15(2):180-4.

30. Kilmer S, Fitzpatrick R, Goldman M. Tattoo Lasers. eMedicine. 2008 Jun. Available at:

www.emedicine.medscape.com/article/1121212-overview (Accessed February 2011).

31. Straetemans M, Katz LM, Belson M. Adverse reactions after permanent-makeup procedures. N Engl J Med. 2007 Jun;356(26):2753.

32. Gallardo MJ, Randleman JB, Price KM, et al. Ocular argyrosis after long-term self-application of eyelash tint. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006 Jan;141(1):198-200.

33. Weiler HH, Lemp MA, Zeavin BH, Suarez AF. Argyria of the cornea due to self-administration of eyelash dye. Ann Ophthalmol. 1982 Sep;14(9):822-3.

34. Teixeira M, De Wachter L, Ronsyn E, Goossens A. Contact allergy to para-phenylenediamine in a permanent eyelash dye. Contact Dermatitis. 2006 Aug;55(2):92-4.

35. Kaiserman I. Severe allergic blepharoconjunctivitis induced by a dye for eyelashes and eyebrows. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2003 June;11(2);149-51.

36. Higgenbotham EJ, Schuman JS, Goldberg I, et al. One year, randomized study comparing bimatoprost and timolol in glaucoma and ocular hypertension, Arch Ophthalmol. 2002 Oct;120(10):1286-93.

37. Smith S, Fagien S, Somogyi C, et al. Eyelash growth in subjects treated with bimatoprost ophthalmic solution, 0.03%: a multicenter, randomized, double-masked, vehicle-controlled, parallel study. In: Poster presented at American Academy of Dermatology’s 67th Annual Meeting, March 6-9, 2007; San Francisco, CA.

38. Allergan. Latisse package insert. Irvine, CA.

39. Allergan Medical Affairs. 2010 June.

40. Scheinman PL. Is it really fragrance free? Am J Contact Dermat. 1997 Dec;8(4):239-42.

41. Rutherford T, Nixon R, Tam M, Tate B. Allergy to tea tree oil: Retrospective review of 41 cases with positive patch tests over 4.5 years. Australas J Dermatol. 2007 May;48(2):83-7.