My eyes are dry with these lenses.” I remember hearing about contact lens discomfort (CLD) for the first time as a novice optometry student. That was decades ago, and just yesterday I heard it again, and again and again.

With so many contact lens options available today, there’s no reason anyone should be experiencing discomfort. For too long, we’ve sort of accepted it as a cost of doing business, so to speak, for contact lens wear. What are the factors that influence this and ideally prevent it?

Believe it or not, CLD can be controlled. Just like fitting contact lens multifocals, it’s manageable if you can manage expectations. I’ll be honest—some patients will never be comfortable with their contact lenses. Their expectations are too high, no matter what you do. But, those with reasonable expectations can be made reasonably comfortable most of the time.

The Comfort Zone

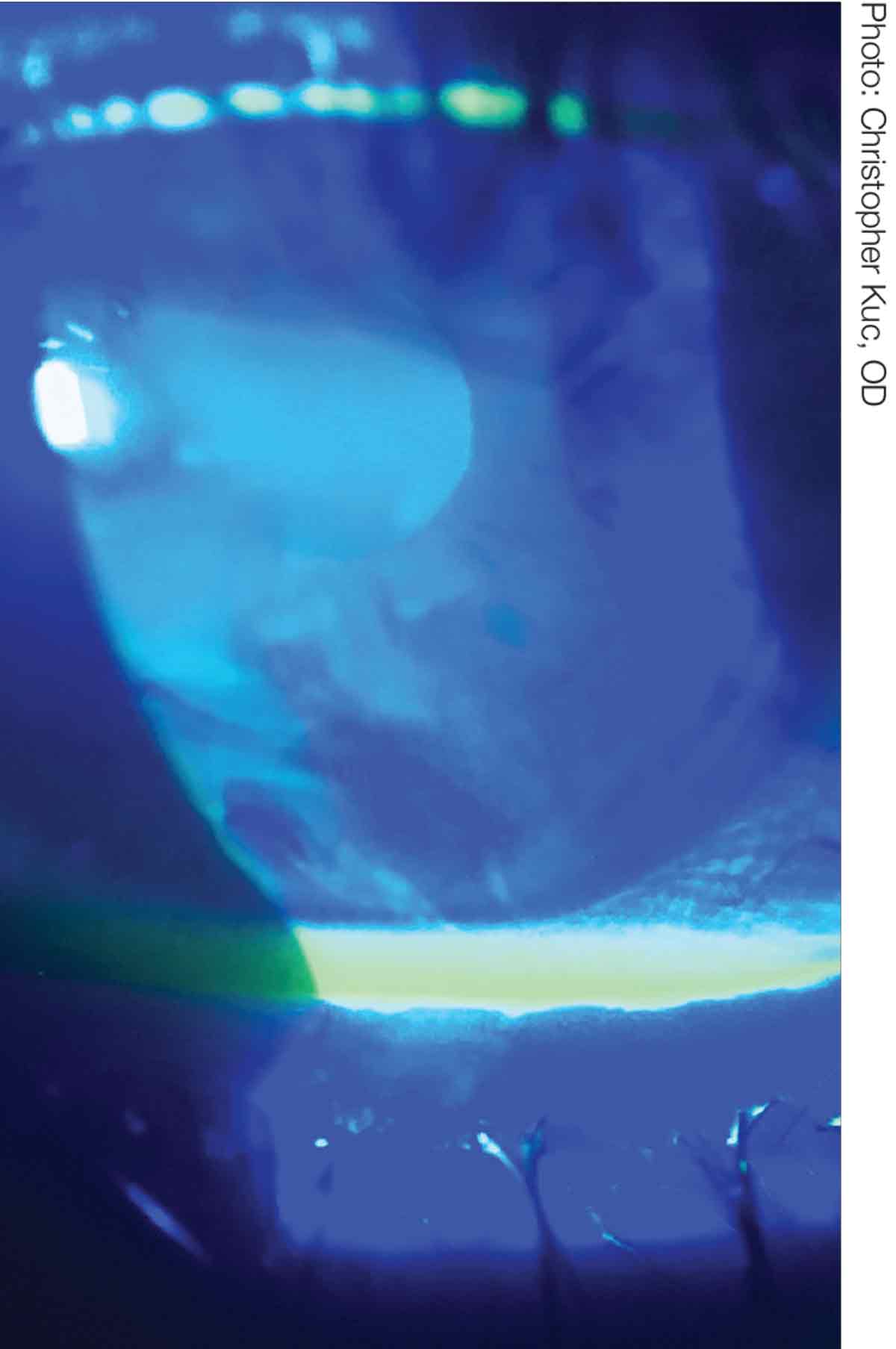

|

| Reduction in tear break-up time is easily assessed and has direct correlation to CLD. Click image to enlarge. |

Years ago, I wrote about the comfort zone. Imagine your patients coming in with a comfort gauge on their forehead. Now, we know that the needle isn’t always in the same position 24/7, as it varies and changes. All kinds of factors can make that needle move. Why? Because the tear film is dynamic; it is never the same all the time. It’s the same for contact lens comfort; it will change along with the tear film. Whatever impacts the tear film impacts the contact lens. What we try to do is keep the patient in the comfort zone as long as we can.

How do we accomplish this? Well, our treatment strategies fall into two distinct categories: lens-based and disease-based. These categories will help you organize your thinking when new treatments become available, just as it helped me build my own algorithm for CLD.

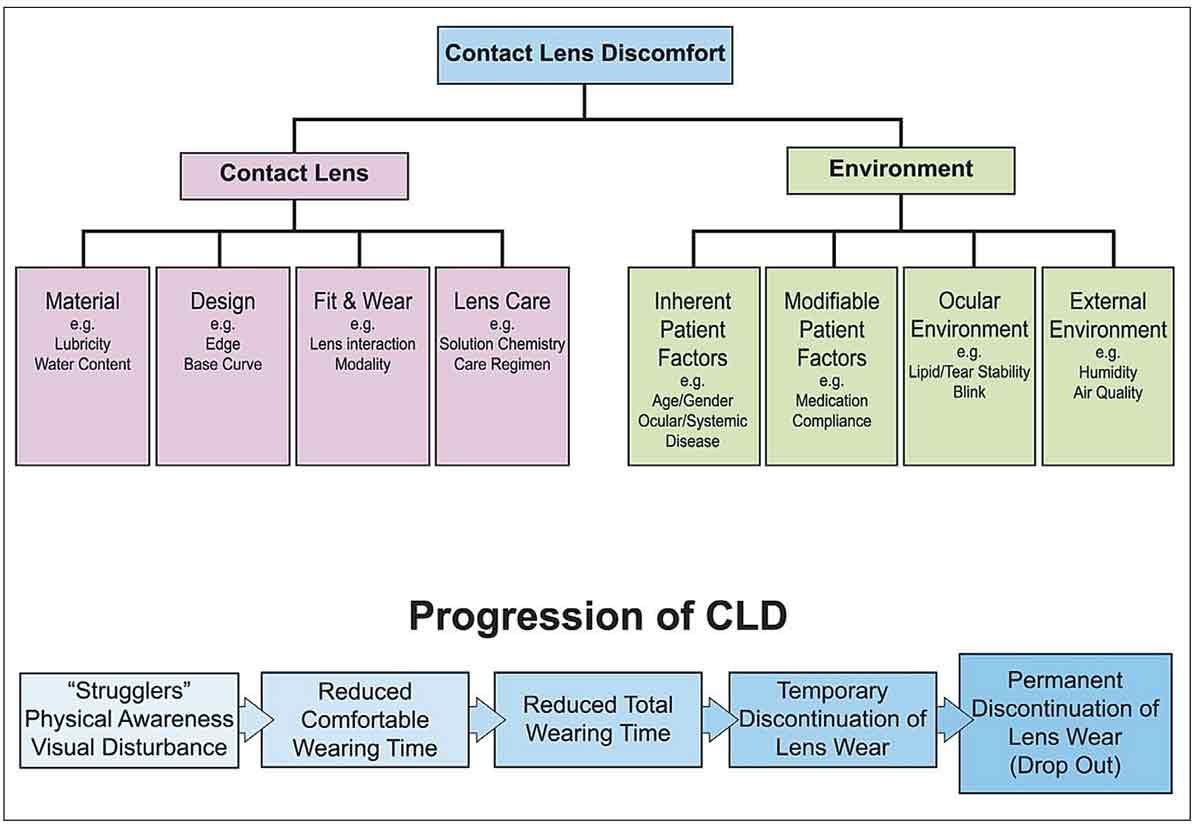

The TFOS International Workshop on Contact Lens Discomfort led by Jason Nichols, OD, is great compilation of peer-reviewed knowledge that goes into detail about the progression of contact lens dropout. The patient first goes to lens awareness, followed by reduced comfortable wearing time, reduced total wearing time, temporary discontinuation of wear, ending in permanent discontinuation of lens wear (drop out.)

Much of the treatment portion is devoted to lens-based treatments. In fact, most of the contact lens education today covers lens-based treatments. The yearly survey on contact lens dryness, also piloted by Dr. Nichols, gives a window into the current thinking by our peers. Again, the survey points to most of the treatments performed being lens-based and, when you talk to contact lens manufacturers, many of their suggestions for treatments are lens-based.

Lens-based Treatments

The survey’s reigning treatment champion for as many years as I can remember is daily disposable lenses; increase comfort by decreasing lens replacement time. Does it work? For many patients, yes. The disadvantages are more lenses, more costs and more plastic, but in terms of comfort, they work. Just like everything else, they don’t work for everyone—every seasoned clinician most likely has a failure story. We need to consider the cause of dryness, water content, type of lens material and many other factors.

|

| Classification of contact lens discomfort as described in the TFOS International Workshop on Contact Lens Discomfort. Click image to enlarge. |

The next treatment on the popular list is rewetters—personally, I love them. Artificial tears are the backbone of dry eye treatment and the modern day rewetters are re-versions of artificial tears. There is so much technology in artificial tears; it’s mind-blowing when you think about it. An artificial tear inventor once told me these products are so sophisticated, he wouldn’t be surprised if they would be a formidable challenge to some of the dry eye drugs on the market today.

To make things clear, I’m talking about the new rewetters, not the old ones. In the past, they were multipurpose solutions just put into a smaller bottle, like chemical disinfectants used as rewetter drops—I run from those.

My first choice of rewetters have sodium hyaluronate acid (HA) in them. HA is almost a miracle component for rewetters and artificial tears in general. In simple terms, HA is a large molecule with long chains. When the patient blinks, rather than being washed out like thicker drops, the HA chains line up, lay themselves down and remain in the eye. They seem to have longer residence time on the ocular surface, and longer residence time means longer retention of benefit—which means more time in the comfort zone.

Recently I had a patient who said her rewetters didn’t work very well (she was using a generic re-versioned MPS one). She loved the sample I gave her (with HA) but couldn’t remember the name and got the other one. After I feigned disappointment, I told her I’m just glad she came back to ask.

Disease-based Treatments

This is the idea is to use treatments for the ocular surface for discomfort. Like I mentioned earlier, discomfort is tied to tear film, and if the tear film is inadequate, discomfort usually follows. Fortify the tear film and you will move the comfort gauge. Basically, the way to fortify is to use conventional dry eye treatments.

I look at dry eye in terms of triggers, which come from the environment. Dry eye correlates with weather: high temperature, low humidity and high pollen counts. Does it impact the tear film and discomfort? Of course. I practice in Southern California and we say that we don’t have winter any more. It seems like pollen surrounds us all year round.

In general, dry eyes make allergies worse; allergies make dry eye worse. So, what to do? I prescribe antihistamine drops for all my CLD patients BID before application and after lens removal every day. This is my first-line treatment, but if more help is needed, I add on other viable treatments: dry eye medications such as cyclosporine or lifitegrast, and steroids like loteprednol and meibomian gland treatments.

My philosophy is to use treatments from both categories: lens-based and disease based-treatments. The more severe the condition, the more treatments from both categories. Mild cases may take just one treatment; severe treatments require more. I find that using both categories optimizes outcomes greatly.

Lid Wiper Epitheliopathy

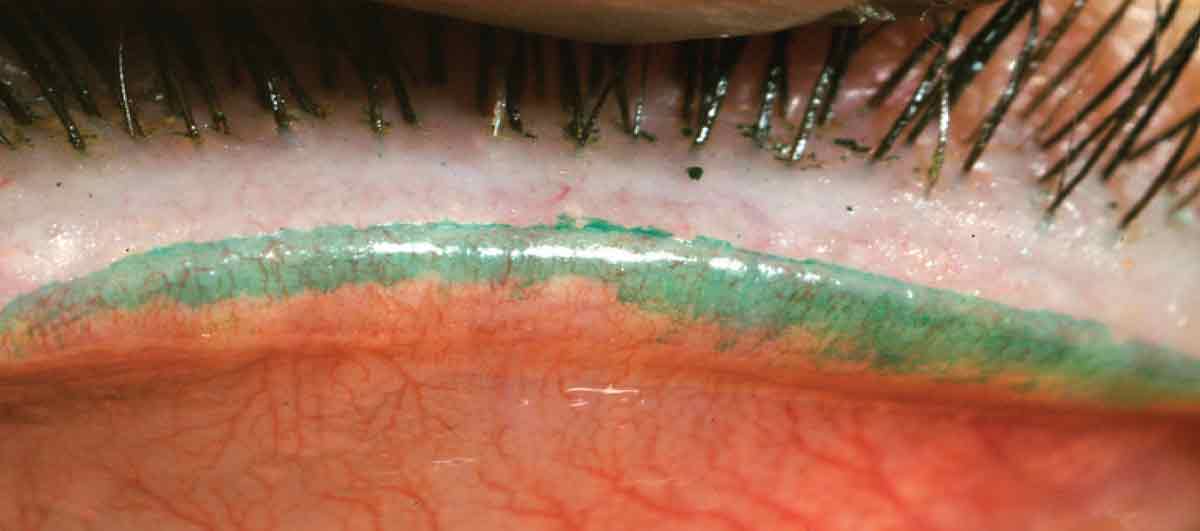

Donald Korb and colleagues first described lid wiper epitheliopathy (LWE) decades ago. They were able to connect it to contact lens dryness and it was actually a new objective sign of CLD. I bring this up because most of the way we detect discomfort is based on what the patient tells us—subjective symptoms. The comfort gauge is essentially a subjective sign. Having an objective sign such as LWE helps with our diagnosis, but it goes beyond that. We can also use objective signs to monitor progress. Lots of time, there is a disconnect between signs and symptoms, especially in ocular surface disease. Many times, the patient feels they are not progressing, but in actuality, they are. Monitoring progress with more than just symptoms can be valuable in keeping the patient motivated and helps to manage expectations.

|

| On a scale from zero to four, LWE in this patient is quite severe at a grade three. Click image to enlarge. |

Does anything help LWE? Originally, prescribing steroids was recommended; they work well, but they are not without pitfalls such as pressure spikes. Most steroid courses are usually no more than two to four weeks, leaving out maintenance therapy. Recently, rewetter drops have been shown to reduce LWE. Again, another reason why I love HA and rewetters. They reduce LWE, relieve symptoms, are easily available because there is no need for a prescription and are a reasonable cost—what’s not to love?

Changing Solutions

Just a few years out of optometry school I attended a lecture by Pat Caroline, who stated, “solutions are the guilty until proven innocent.” Little did I realize his words explained the reason why one of the most popular treatments for CLD works even today. That treatment is changing solutions.

TFOS International Workshop on Contact Lens Discomfort: Executive SummaryAn 18-month workshop included 79 experts, who were assigned with taking an evidence-based approach at evaluating contact lens discomfort. Below are the eight subcommittees and the experts’ evaluation: Definition and Classification Epidemiology Contact Lens Materials, Design and Care Neurobiology of Discomfort and Pain One hypothesis is the possibility of mechanical stimulation of the nociceptors in the lid wiper region of the eyelids. Stimulation of subacute inflammation of the ocular surface during lens wear may occur, and nerves can respond to the production of a variety of inflammatory mediators, including cytokines and arachidonic acid metabolites, the authors explained. Contact Lens Interactions with the Ocular Surface & Adnexa Contact Lens Interactions with the Tear Film Trial Design and Outcomes Management and Therapy The paper concludes by emphasizing how important it is that the process of prevention and management of contact lens discomfort starts early, even before the onset of symptoms, to improve the long-term prognosis of successful, safe and comfortable contact lens wear. 1. Nichols JJ, Willcox M D.P., Bron AJ, et al. The TFOS international workshop on contact lens discomfort: executive summary. Inv Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:TFOS7-13. |

Hydrogen Peroxide

Does anyone remember the original term for MPS? Chemical disinfection—yes, chemicals in the solution are used to kill bacteria and other microbial organisms. These are the same chemicals we soak lenses in and put into the eye. Now, over the years, the chemicals have become infinitely better; they disinfect and are much more mild to the eye. Remember, though, that they are still chemicals and irritate, cause dryness, redness and discomfort. The incidence is much, much less than before, but there are still patients who are sensitive. This is where peroxide-based solutions come into play. Many times changing to peroxide works wonders, if you know the proper situation when to prescribe it.

I find that peroxide works best when the patient experiences reduced comfortable wearing time, which is early in the progression of CLD. Switching to peroxide successes diminishes as the discomfort becomes more severe. For instance, I have had little success switching to peroxide when the patient is undergoing temporary discontinuation of lens wear or has already dropped out. The patient, unfortunately, is too far gone for peroxide to save the day. For me, peroxide is invaluable, especially when you know when to use it.

Changing Lens Materials

This is another strategy to reduce or eliminate CLD. There are many newer materials that are designed to address discomfort—non-silicone hydrogel, those that have superior retention of water and others that have great surface attributes. If you like monthly replacement, changing materials is a viable option, but which materials to use and when? I have not figured this one out yet; all I know is one material does not work for everyone. What I try to do is have different materials from different manufacturers available. Almost like fitting multifocals, just don’t have one manufacturer available; I recommend having multiple fitting sets.

It’s funny: when I speak on this topic, I always get different responses. It reminds what someone said about pizza in New York. If you have 40 New Yorkers in a room and ask, “What’s the best pizza?” you’ll get 40 different answers.

Sometimes, you will get instant success treating CLD. Other times, it is a long journey that can feel like a roller coaster to patients. No matter what happens, managing expectations at the outset will greatly increase your chances for success.

Dr. Hom is an internationally recognized expert and researcher in therapeutics, dry eye, contact lenses, allergy and glaucoma. He has written four books and published over 200 papers and peer-reviewed abstracts. He does research support for AbbVie, Allergan, Novartis, Vyluma and Surface Pharmaceuticals.