When we think of allergy, we think of inflammation. We often consider inflammation a bad thing, but in actuality it’s a good thing—part of the natural process. Without it, we have no healing, and inflammation is necessary to start the healing process. But what is the difference between good and bad inflammation? Time. Inflammation is meant to go away, but when it becomes chronic and doesn’t leave, it becomes a bad thing.

Allergy is chronic inflammation. It goes on and on and, many times, it becomes worse—this is known as the allergy cascade. Allergy is a glitch in the immune system, as it doesn’t work as it was meant to. Inflammation is triggered but does not stop; it keeps going.

|

|

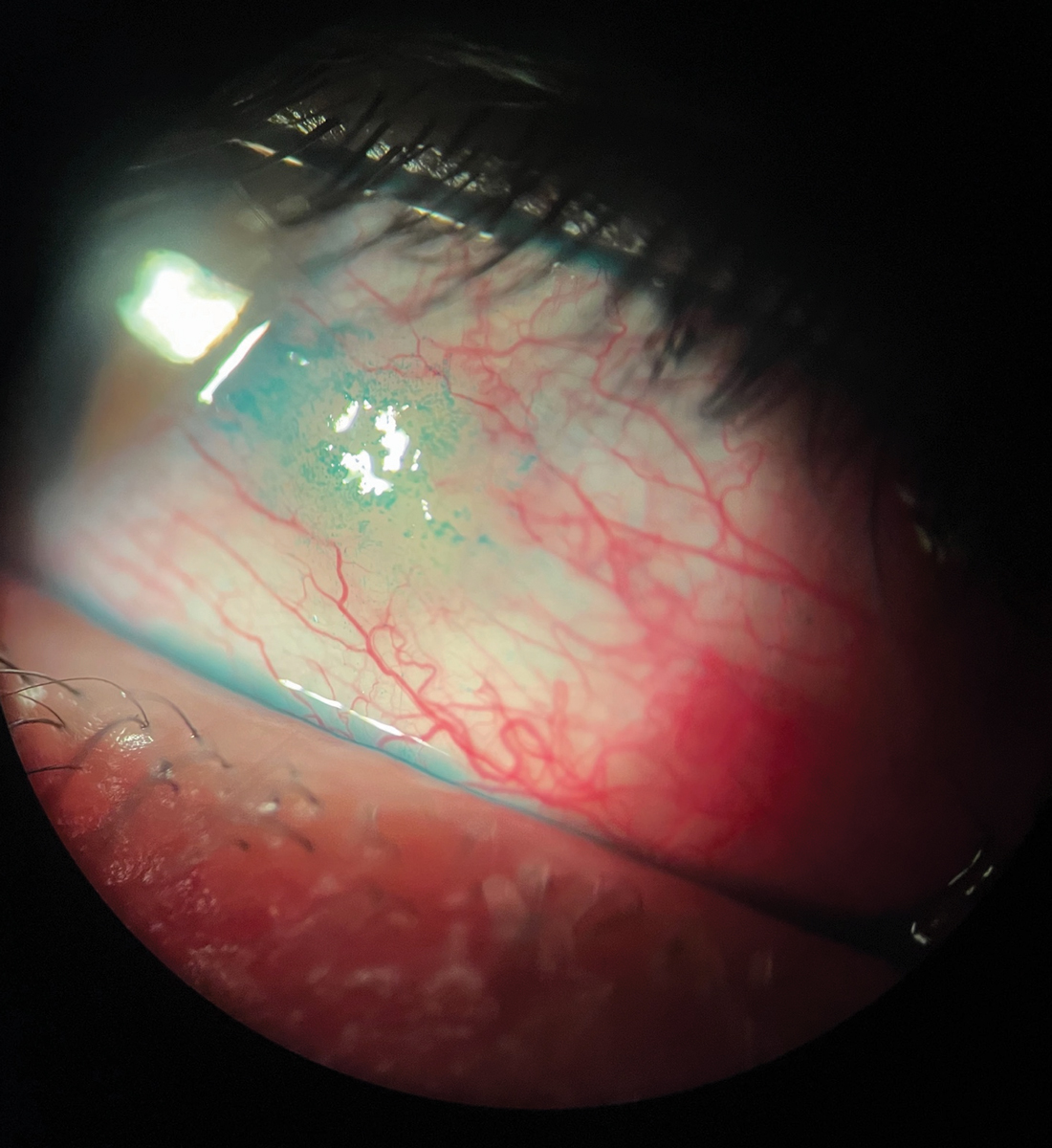

Fig. 1. Redness seen in ocular allergy. This patient also had a pinguecula and lissamine green staining. Click image to enlarge. |

Our immune system is our defense against pathogens, microbial antigens, allergens and other threats. When a pathogen is present, our immune system kicks in. The first line of defense is physical, with one response being to itch and rub our eyes. Rubbing our eyes is meant to physically remove the pathogen that is invading. In the case of allergy, it is usually grains of pollen. Itch is part of the physical defense system. Of course, in the case of allergic conjunctivitis, the itch becomes chronic because there is the glitch.

Once a pathogen gets into the eye, another defensive physical action would be to flush it out. When irritation hits, one reaction is to wash it out. For the ocular surface, there is a built-in plumbing system: the pathogen enters, irritates the eyes and tear flushing happens, which is why our eyes get watery.

Using fluid on the external surface is one manner of getting rid of a allergen. Internal fluid is another method. A defensive move of the immune system is to send fluid to the point of attack, which physically blocks the invader. It also serves to help send inflammatory cells to the point of attack. Inflammatory cells are the soldiers that combat the pathogen, and sending fluid to the area manifests as swelling.

Getting the inflammatory cells to the right location requires efficient transport. They need open pathways (blood vessels) to get to their destination. When called upon, the inflammatory cells travel through the vessels to the point of attack. In order to facilitate this, the vessels get larger or widen. We see this clinically as hyperemia or redness (Figure 1).

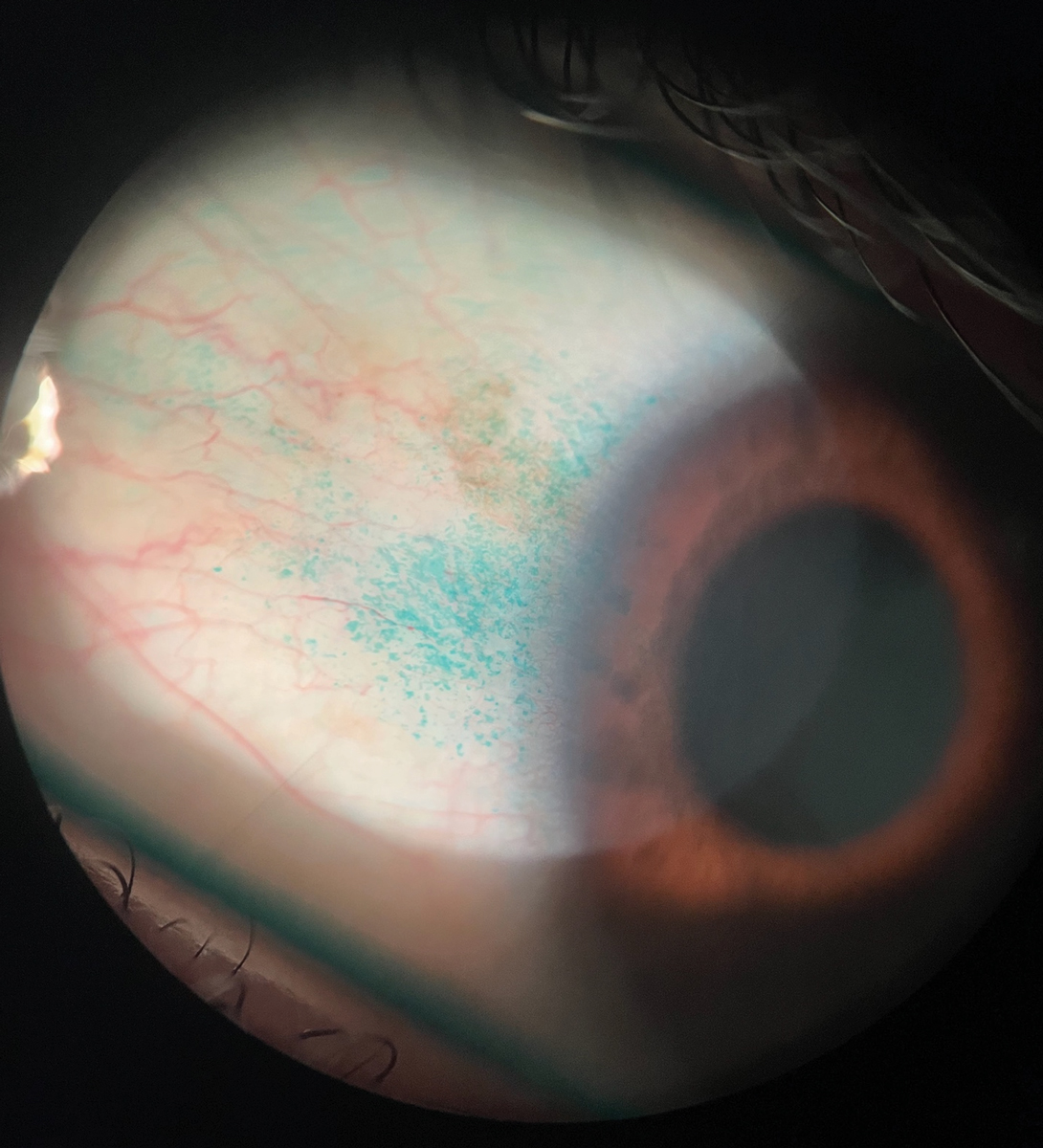

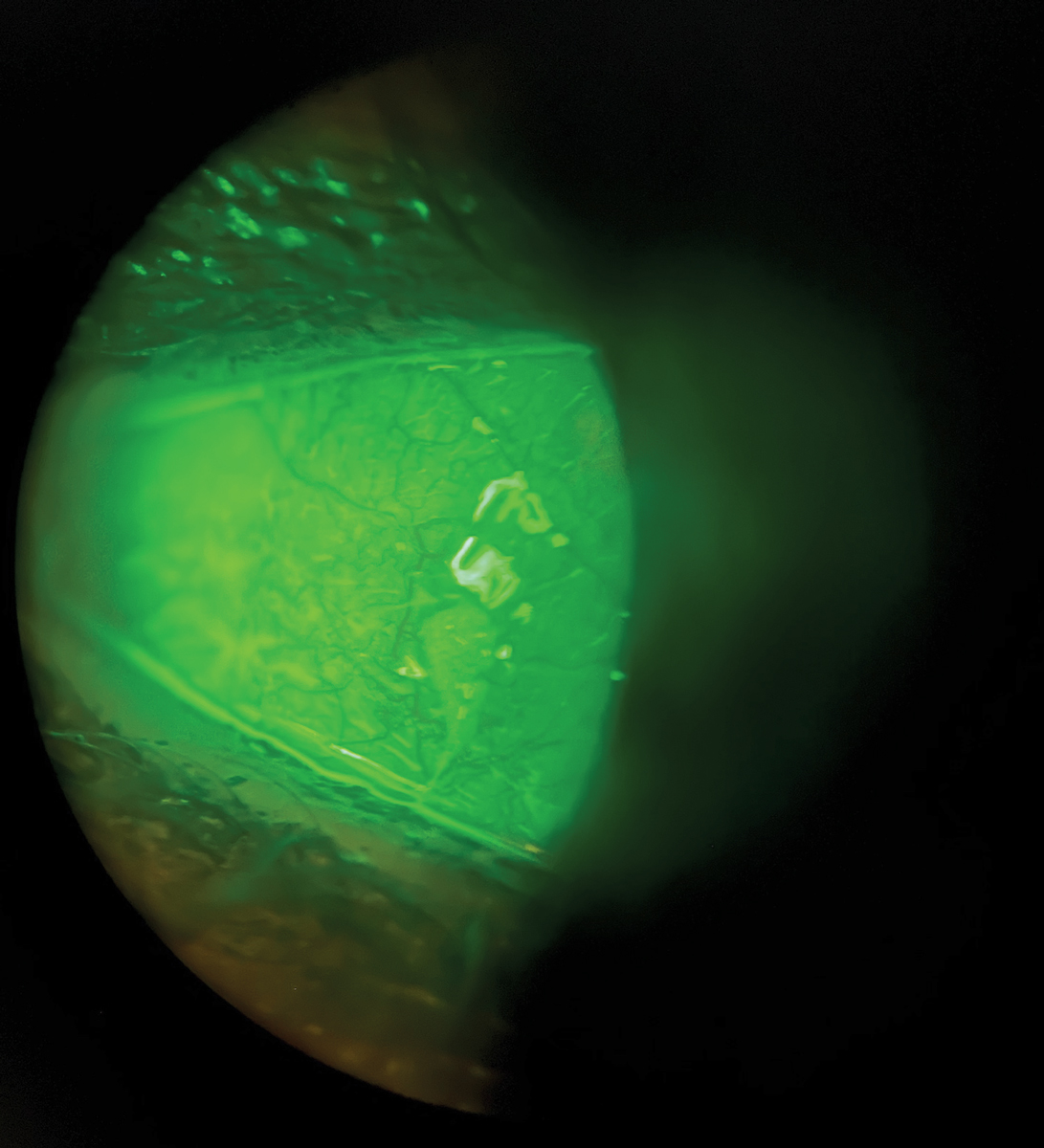

All of these immune defense strategies comprise the signs and symptoms we see in allergic conjunctivitis: itch, watery, swelling and redness. Many times vital dyes staining, such as lissamine green and fluorescein, will also be seen (Figures 2 and 3).

Table 1. Preservative-free Ocular Lubricants | |||

| Category | Brand name | OTC or Rx | Dosing |

CMC containing | Allergan: Refresh Optive, Refresh Optive Advanced, Refresh Tears Plus, Refresh Liquigel, Refresh Celluvisc. TheraTears: TheraTears | OTC | As needed |

| HPMC containing | Alcon: Tears Naturale Free, Bion Tears | OTC | As needed |

| Hyaluronic acid containing | J&J: Blink Tears. Hylo Eye Care: Hylo-Comod, Hylo-Tear, Hylo-Fresh, Hylo Gel, Hylo-Care, Hylo-Parin (also contains heparin), Hylo-Dual | OTC | TID/as needed |

| Glycerin containing | Oasis Tears: Oasis Tears, Oasis Tears Plus. Allergan: Refresh Optive, Refresh Optive Advanced, Refresh Digital | OTC | As needed |

| Mineral oil or petrolatum containing (ointments) | Akorn: Akwa Tears. Allergan: Refresh PM, Bausch + Lomb: Soothe XP. Alcon: Systane Nighttime | OTC | Once a day at bedtime |

Polyethylene glycol containing | J&J: Blink Tears. Alcon: Systane, Systane Ultra | OTC | As needed |

| Polyethylene glycol containing | Refresh classic, Optics mini drops | OTC | As needed |

Ocular Allergy

Itching, wateriness, swelling and redness are all domains in the Total Ocular Symptom Score (TOSS) questionnaire.1,2 TOSS is part of new guideline recently published in Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, the official publication of the American College of Asthma Allergy and Immunology.3 I was part of their ocular allergy committee that created a guideline for treatment and management of allergic conjunctivitis geared for allergists (or as some of them prefer to be referred to, clinical immunologists).

Ocular allergy affects 36% of the United States population, and it worsens each year.4,5 The classifications of the disease are seasonal allergic conjunctivitis (SAC), perennial allergic conjunctivitis (PAC), vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC), atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) and contact blepharoconjunctivitis, with 95% to 98% of cases being SAC and PAC.6 Allergic conjunctivitis symptoms overlap with those of dry eye—more than 50% of patients with ocular allergy also having dry eye.7 Differentials also include irritative conjunctivitis, Demodex and infectious conjunctivitis, among others.

Allergists depend on many different testing modalities, most not specific to the eye. Skin prick testing is the first-line approach to diagnose immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated sensitivity owing to its sensitivity, efficacy, safety and feasibility, and is performed for pollens, mites, animal dander and mold.8,9 Blood tests such as serum-specific IgE measurements should be considered when skin prick testing is inconsistent with the patient history, cannot be performed or to quantify specific IgE to naive allergens.9

Simple allergen avoidance measures such as eyewear protection, frequent washing of clothes, hypoallergenic bedding and bathing before bedtime may all help to halt disease progression. It’s also helpful to reduce exposure to pet dander by keeping animals out of the bedroom and using both high-efficiency particulate absorbing (HEPA) air filters and HEPA vacuums; using just an air filter or vacuum alone is not as effective as both.

Telling patients to avoid eye rubbing is easier said than done. They will unknowingly rub their eyes at night when sleeping, which is even more reason to prescribe an allergy drop. Some practitioners recommend washing hair regularly, but that can be quite time consuming for some patients. Instead, we recommend covering their hair if washing is too difficult.

Cold compresses and refrigerated artificial tears may also provide symptomatic relief.10 Avoidance and non-pharmaceutical interventions are preferred by some patients. I have found younger adults are more likely to try non-pharmaceutical treatments first before drug therapies.

|

|

Fig. 2. Lissamine green staining in allergic conjunctivitis. Click image to enlarge. |

Treatments

There are numerous treatment options for ocular allergy. Refrigerated artificial tears help wash away allergens and dilute inflammatory mediators on the eye. Preservative-free compounds are preferred to minimize toxic effects. Artificial tears may be low, mid or high viscosity. Low-viscosity tears, usually prescribed for mild conditions, cause little interference with vision and offer great comfort. However, with a low residence time, the retention of benefits is less than mid or higher viscosity tears. The latter have greater blurring effects, however, and are reserved for more severe cases. They can be best used at night.9,10

Ocular decongestants are usually over-the-counter and can reduce ocular erythema, but unfortunately, they have little effect on decreasing itching. Personally, we rarely prescribe ocular decongestants, if at all.

Oral antihistamines are frequently used by patients before seeking medical attention; however, the use and especially overuse of oral antihistamines—particularly first-generation antihistamines—may worsen dry eye syndrome.9 Topical antihistamines are preferable to oral forms because of rapid onset and relief. With their high efficacy and safety margin, topical antihistamines are often used as first-line treatment for allergic conjunctivitis.

Singulair (montelukast, Merck) has been reported to be more efficacious than placebo in treating seasonal allergic conjunctivitis.11 Mast cell (MC) stabilizers inhibit degranulation of MCs and prevent the release of mast cell mediators. With the availability of newer agents that possess both antihistamine and MC-stabilizing properties, the use of single-action MC stabilizers is not prescribed often. Many newer topical ophthalmic drugs work both as antihistamines and MC stabilizers. They require less frequent instillation owing to longer duration of action and have better tolerability than single-action antihistamines.12

|

|

Fig. 3. Fluorescein staining in allergic conjunctivitis with dry eye. Click image to enlarge. |

Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ketorolac (Toradol, Sagent Pharmaceuticals), is FDA-approved to treat SAC.9 These drugs have pretty much fallen off the map in terms of prescribing for allergic conjunctivitis, but topical steroids are highly efficient. Older ocular corticosteroids such as prednisolone, dexamethasone or fluorometholone may induce cataract formation and IOP spikes. Loteprednol, in which the ketone group at carbon-20 has been substituted with an ester group, does not increase the risk of cataracts, but these drugs also may be associated with IOP spikes.12

Topical calcineurin inhibitors such as cyclosporine or tacrolimus may be considered in severe or refractory allergic conjunctivitis, VKC and AKC.13 I routinely prescribe cyclosporine or other dry eye medications for allergic conjunctivitis, usually in concert with an antihistamine or antihistamine MC stabilizing drop.

As previously mentioned, most of ocular allergy also has a dry eye component. Prescribing both a dry eye and allergy topical medication will treat both conditions simultaneously; I have found this approach highly efficacious.

Immunotherapy

This treatment is outside the range of most eye care professionals, but on the flip side, it’s the backbone treatment for clinical immunologists. It is a good option for patients with inadequate symptom control. Despite using pharmacotherapy and allergen avoidance, immunotherapy can work when those fail. Sometimes, patients are unable to tolerate medications or find long-term compliance difficult. These patients can also be successful with immunotherapy.

There are currently two modalities for allergen immunotherapy: subcutaneous and sublingual. Three sublingual therapy tablets have been approved by FDA, which can probably be prescribed by some ODs in certain states: Grastek (Timothy extract), Oralair (cross-reacting sweet vernal, orchard, perennial rye) and Ragwitek (ragweed extract).

Allergen immunotherapy increases the sensitivity threshold and helps decrease ocular symptoms and medication use.11 My personal experience with immunotherapy has been highly successful. After suffering with allergies since childhood, immunotherapy greatly reduced my symptoms over the course of treatment and it was efficient at helping ocular allergy symptoms, too. Immunotherapy also is an opportunity to promote a team approach with pediatricians and allergists.

There is controversy among allergists regarding management by those who aren’t allergy-trained. Companies offer to come into non-allergy practices and set up skin prick testing along with immunotherapy. The controversy lies in the outcomes of these set-ups. Allergists contend the amount of allergen used is minimal and not very effective. The reasoning behind using minimal amounts is to avoid anaphylaxis in non-allergy practices, but outcomes are not as efficient as when it is closely monitored by an allergist.

Table 2. Selected Artificial Tears by Viscosity | |||

| Low viscosity | Medium viscosity | High viscosity | Emulsion |

| Alcon: Systane Ultra and Classic, Tears Naturale

| Allergan: Refresh Gel drops, Refresh Liquigel | Allergan: Refresh Celluvisc, Refresh PM | Bausch Health: Soothe XP |

Maintenance Therapy

Within my area of practice, SAC and PAC seem to have merged into one subtype. As a result, we have many patients on topical maintenance therapy. Because of the high safety margin of topical antihistamines and combination drops, maintenance therapy is very safe.

What are the advantages? As stated previously, there is something called the allergy cascade. In the early stages, allergy can be mild, but as time goes on, the condition (left untreated) worsens; more inflammation yields more inflammation. The key is to keep chronic conditions under control. When uncontrolled, greater severity happens. I tell my patients that maintenance therapy will save a lot of time and prevent suffering. Life is much easier for both the patient and doctor when ocular allergy is kept under control with maintenance therapy.

Keep in mind that there will be times when flare-ups occur. When we see these in allergic conjunctivitis, we usually add a topical steroid such as loteprednol BID and we always keep immunotherapy as an option. Future directions for treatment include leukotrienes blockers, platelet activating factor inhibitors (ISV-611), anti-IgE therapy—primarily to reduce and diminish the amount of allergen/antibody response—and regulation of adhesion molecules and chemokines (ICAM-1, ICAM-3, VCAM-1).

Now that you understand the clinical implications of ocular allergy, it’s time to implement this knowledge into your practice and help get your patients’ symptoms under control with the many treatments and therapies available today.

Dr. Hom is an internationally recognized expert and researcher in therapeutics, dry eye, contact lenses, allergy and glaucoma. He has written four books and published over 200 papers and peer-reviewed abstracts. He does research support for AbbVie, Allergan, Novartis, Vyluma and Surface Pharmaceuticals.

1. Andrasko G, Ryen K. Corneal staining and comfort observed with traditional and silicone hydrogel lenses and multipurpose solution combinations. Optometry. 2008;79(8):444-54. 2. Carnt N, Willcox MD, Evans V, et al. Corneal staining: the IER Matrix study. Contact Lens Spectrum. September 1, 2007. 3. Bandamwar KL, Papas EB, Garrett Q. Fluorescein staining and physiological state of corneal epithelial cells. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2014;37(3):213-23. 4. Bakkar MM, Hardaker L, March P, et al. The cellular basis for biocide-induced fluorescein hyperfluorescence in mammalian cell culture. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e84427. 5. Khan TF, Price BL, Morgan PB, et al. Cellular fluorescein hyperfluorescence is dynamin-dependent and increased by Tetronic 1107 treatment. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2018;101:54-63. 6. Bright FV, Burke SE, Chalmers RL, et al. Contemporary research in contact lens care. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2013;36(S1):S22-7. 7. Mok KH, Cheung RWL, Wong BKH, et al. Effectiveness of no-rub contact lens cleaning on protein removal: a pilot study. Optom Vis Sci. 2004;81(6):468-70. 8. Pucker AD, Nichols JJ. Impact of a rinse step on protein removal from silicone hydrogel contact lenses. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86(8):943-7. 9. Eiden B. Does one contact lens solution fit all? Review of Cornea & Contact Lenses. May 18, 2011. 10. Quinn TG. Making sense of contact lens care. Contact Lens Spectrum. November 1, 2017. 11 Reindel W, Merchea MM, Rah MJ, Zhang L. Meta-analysis of the ocular biocompatibility of a new multipurpose lens care system. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:2051-6. 12. Johnston SP, Sriram R, Qvarnstrom Y, et al. Resistance of Acanthamoeba cysts to disinfection in multiple contact lens solutions. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:2040-5. 13. Hughes R, Kilvington S. Comparison of hydrogen peroxide contact lens disinfection systems and solutions against Acanthamoeba polyphaga. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:2038-43. 14. Lever AM, Sutton SVW. Antimicrobial effects of hydrogen peroxide as an antiseptic and disinfectant. In: Handbook of Disinfectants and Antiseptics. Ascenzi JM, ed. CRC Press, 1995. 15. Linley E, Denyer S, McDonnell G, et al. Use of hydrogen peroxide as a biocide: new consideration of its mechanisms of biocidal action. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:1589-96. 16. Ward M. Corneal and scleral GP contact lens care. Contact Lens Spectrum. November 1, 2018. 17. Benoit DP. Proper care of modern GP lenses. Contact Lens Spectrum. May 1, 2015. 18. Watanabe RK, Rah MJ. Preventative contact lens care: Part III. Contact Lens Spectrum. August 1, 2001. 19. Young, R. The evolution of contact lens materials. Contact Lens Spectrum. November 1, 2017. 20. Zhu H, Bandara M, Kumar A, et al. Contribution of regimen steps to efficacy of multipurpose solutions used to disinfect silicone hydrogel contact lenses. XVIII International Congress of Eye Research, Beijing, September 24-29, 2008. 21. Butcko V, McMahon TT, Joslin CE, Jones L. Microbial keratitis and the role of rub and rinsing. Eye Contact Lens. 2007;33(6):421-3. 22. Cancrini G, Iori A, Mancino R. Acanthamoeba adherence to contact lenses, removal by rinsing procedures, and survival to some ophthalmic products. Parassitologia. 1998;40:275-8. 23. Pens CJ, Costa MD, Fadanelli C, et al. Acanthamoeba spp. and bacterial contamination in contact lens storage cases and the relationship to user profiles. Parasitol Res. 2008;103:1241-5. 24. Szczotka-Flynn LB, Pearlman E, Ghannoum M. Microbial contamination of contact lenses, lens care solutions, and their accessories: a literature review. Eye Contact Lens. 2010;36(2):116-29. 25. Vermeltfoort PB, Hooymans JM, Busscher HJ, et al. Bacterial transmission from lens storage cases to contact lenses-effects of lens care solutions and silver impregnation of cases. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2008;87:237-43. |