No matter what an eye care practice focuses on, many practitioners likely field questions regarding the potential for LASIK treatment. Patients ask for our opinions and recommendations on the procedure’s suitability for them, as many have more than likely read reports of complications in the media and remain wary. So, what should we tell them? Below is a summary of some of the latest data and consensus opinions regarding questions that many of us may face during the perioperative care of a refractive surgery patient.

1. Post-LASIK Ectasia

The first example is bilateral thinning of the cornea post-procedure, or corneal ectasia, which occurs in some patients with a thin residual stromal bed, particularly those with high preoperative myopia, an occurrence that alters the structural integrity of the cornea. Those patients with uncommon corneal shapes pre-procedure are even more at risk of onset.

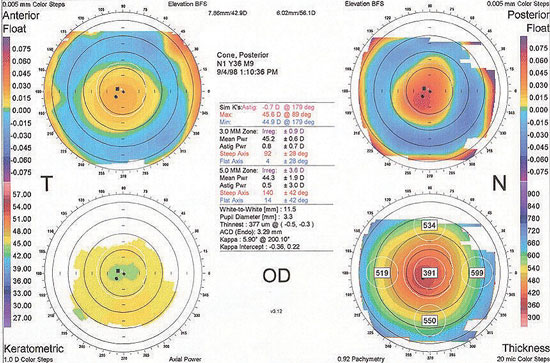

|

| This corneal topography shows minimal anterior corneal elevation and astigmatism. However, there is a significant posterior elevation, which suggests early posterior keratoconus. The thinnest area of the cornea also corresponds to the apex of the posterior elevation. This patient would be a poor LASIK candidate. |

Take this example: a 31-year-old male presented to the clinic wearing monthly disposable contact lenses and expressed interest in LASIK. Corneal topography indicates that he has mild corneal irregularity and inferior steepening. Ultimately, the practitioner suspects that his patient has mild keratoconus, though his vision corrects to 20/20 with refraction. He exhibits 3D of myopia, 1D of astigmatism and a corneal thickness of 560μm, along with a patient history that reveals refractive stability maintenance over the past five years, suggesting he might be a good candidate for LASIK. However, due to his irregular corneal shape, he is at risk for possibly the most concerning complication that can follow refractive surgery.

Most individuals who develop post-surgical ectasia suffer from structural and visual distortions, somewhat akin to keratoconus, that are not adequately controlled either with spectacles or contact lenses, leaving them with limited options should further adjustment be necessary. To help prevent this problem following surgery, the Ectasia Risk Score System was created to assist with the screening of high-risk patients prior to the procedure.1 The system is based on a series of post-LASIK ectasia cases from 2008, during which several risk factors for the development of the issue were identified. These include:

Abnormal preoperative corneal topography. Moderate-to-severe keratoconus is a definitive contraindication for refractive surgery due to the severe instability of the cornea’s structural bonds, while even milder corneal irregularities or forme fruste keratoconus can increase the risk of postoperative complications.

Low residual stromal bed (RSB) thickness. Research suggests that a minimum of 250μm to 300μm of stromal tissue should be left intact following surgery to help ensure the patient does not develop issues after the procedure. If the RSB is thinner than this range, the risk of ectasia is higher.2 Expected RSB thickness can be estimated using the following rule of thumb: the femtosecond flap should be made approximately 100μm thick, with the laser removing roughly 15μm of stroma per diopter of myopia to be corrected. As such, the preoperative pachymetry values and the patient’s level of refractive error can be predicted to determine anticipated postoperative corneal thickness.

Age. Though keratoconus typically presents itself during adolescence, some cases can manifest in adulthood as well. In younger patients with a family history of keratoconus (and thus a higher genetic predisposition towards developing the disease), a practitioner might consider delaying LASIK treatment until later in the patient’s life. The creators of the Ectasia Risk Score System hypothesized that some of the individuals who ended up developing ectasia following surgery in their study sample did so at a younger age without any other recognizable risk factors noted, and may have eventually developed forme fruste or manifest keratoconus, even if LASIK had not been performed. As such, LASIK surgery runs the risk of preempting the onset of keratoconus and exacerbating progression of the disease.

Lower amount of preoperative corneal thickness. This factor is directly related to the presence of low RSB thickness. In cases in which the patient has less total tissue and some is removed, complications are more likely.

Higher degree of myopia. This is related to residual stromal bed thickness in that a higher degree of stromal tissue must be removed to allow for the successful correction of higher levels of ametropia.

This rating system is not without controversy, as some surgeons find it too simplistic and limiting, especially in its admonition against performing LASIK in some younger patients. While imprecise, it does raise valuable points for discussion that should be individualized to each patient in your evaluation.

At first look, it appears that the patient mentioned above should undoubtedly be excluded from refractive surgery due to his corneal topography findings. But another shortcoming of the rating scale is its reliance on placido disc-based topography systems, which are incapable of demonstrating posterior corneal curvature. Today’s corneal tomography systems, however, can more accurately measure both the anterior and posterior corneal surfaces than earlier technologies. Recent data based on modern corneal tomography collected using devices such as the Pentacam (Oculus) or Orbscan (Bausch + Lomb) also suggest that PRK (instead of LASIK) could be safely performed on mildly irregular cornea patients, provided that the following conditions hold true: First, the patient’s posterior corneal surface must be normal (underscoring the importance of modern tomography’s ability to image it); second, the cornea must be sufficiently thick; third, the patient must have good preoperative best-corrected spectacle acuity to be considered for PRK.3

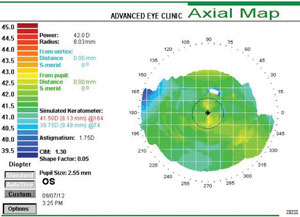

|

| This corneal topography shows a regular LASIK-naïve cornea with average keratometry reading of 40.62D. Flat postoperative corneas may increase the risk of aberration-induced visual disturbances; therefore presurgical keratometry readings should be considered. |

In this case, the practitioner should consider obtaining corneal tomography to confirm that he exhibits a normal posterior corneal surface; if so, he may in fact be a better candidate for PRK than LASIK (given his mild topographical irregularity). His residual stromal bed thickness can be estimated at 560μm minus about 53μm of stroma (15μm x 3.5D of spherical equivalent myopia lost to ablation), for about 507μm. Since PRK might be recommended for this patient over LASIK, there would be no flap thickness to account for, meaning more stromal tissue is left behind. As such, assuming that this patient exhibits a typically regular posterior corneal curvature, he may be a candidate for PRK.

The recent FDA approval of corneal crosslinking and the emerging technology of topography-guided PRK may mean that performing refractive surgery on irregular corneas will become more common. By crosslinking the collagen fibers and strengthening the stroma, the corneal ectatic disease process can be slowed and possibly even halted if the procedure is performed prior to refractive surgery; however, further research is necessary to better quantify this effect.

Though the patient here has mild corneal irregularity, it’s worth noting that some cases of ectasia occur in eyes that were topographically regular preoperatively. So, how do we quantify the ectasia risk in these patients? A recently proposed metric known as percent tissue altered (PTA) may help. It states that during calculation, flap thickness (FT) should be added to the ablation depth (AD), then divided by the preoperative central corneal thickness (CCT), or PTA = (FT + AD) / CCT.4 The study that gave rise to this equation determined that a PTA higher than 40% was the strongest predictive factor of ectasia risk (more so than age, RSB thickness and total Ectasia Risk Score). Because this study was done using topographically normal eyes, however, a lower threshold may be applicable in the case of mildly irregular corneas.

The risk of post-surgical ectasia can never be eliminated, of course, but practitioners can use simple criteria and metrics such as these to estimate a patient’s risk and help them weigh the options. This counseling can be done in the optometrist’s office as part of a preoperative surgical consultation appointment.

2. Small Pupil

Pupil size is another factor to consider prior to recommending LASIK. Consider the following case:

A 26-year-old female contact lens wearer with good ocular health presents for a consultation with refraction values of -5D in each eye and central corneal thicknesses of 580μm. The practitioner also notices that the patient’s pupils are 8mm in dim illumination and questions her regarding the presence of glare or halos during contact lens wear, to which the patient responds negatively. She does, however, report some glare while wearing her spectacles, and wants to know whether she is a good candidate for LASIK.

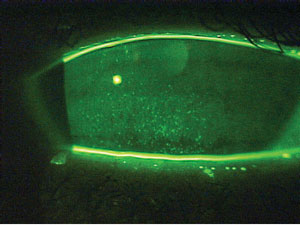

|

| This patient demonstrates marked punctate epithelial staining associated with dry eye syndrome. Aggressive treatment would be indicated before considering LASIK. |

Many patients who undergo refractive surgery have reported the presence of postoperative glare and halos, especially in dim illumination. Conventional wisdom tells us that pupils measuring larger than the laser treatment optical zone prior to surgery increase the risk of visual disruption after surgery. In fact, this relationship has served as fodder for many malpractice lawsuits—so much so that many practitioners now advise these patients against refractive surgery.

Despite this, however, other recent research has disputed the connection between pupil size and visual disturbances, possibly opening the door for a better understanding. One retrospective study considered results from nearly 11,000 eyes of patients aged 18 to 40 who had undergone wavefront-guided LASIK with a 6mm optical zone with mean scotopic pupil diameter being 6.6mm.5 Nearly 27% of these eyes had a pupil diameter of 8mm or larger, yet at six months the researchers observed no correlation between pupil diameter and patient-reported outcomes such as satisfaction, presence of night glare or onset of halos.

The dissociation between pupil size and visual disruptions can possibly be explained by a number of factors. First, the typical treatment zone for LASIK increased from 4mm during the procedure’s earlier days to a more pupil-sparing diameter of 6mm today. Furthermore, some newer ablation algorithms deliver extra pulses to the mid-peripheral cornea in an attempt to decrease spherical aberration.

In this context, how then should we approach a preoperative discussion with a patient with larger pupils? Someone with 8mm pupils historically would have been discouraged from undergoing LASIK; nowadays, perhaps these individuals can simply be counseled that there are conflicting reports in the literature about a higher risk for glare and halos after surgery but that it need not be a contraindication if they are willing to accept the possibility. However, if the patient is on a systemic medication that causes mydriasis (including tricyclic antidepressants and anticholinergics), the risk is definitively higher.

In conclusion, this patient should be counseled regarding the theoretical risk and historical association between large pupils and nighttime glare and halos. But she should also be notified that more recent research has found no association between pupil size and visual complaints. Assuming she is otherwise a good candidate for the procedure, her pupil size should not exclude her from LASIK treatment.

3. High Myopia

Patients with higher degrees of myopia are also at risk for suboptimal refractive surgery outcomes. For such patients, several considerations must be accounted for preoperatively. First and foremost, some may be at greater risk for post-LASIK ectasia, since the correction of higher degrees of myopia entails the removal of more stromal tissue, leading to thinner postoperative corneas and higher PTA values. Though PRK is a better option than LASIK to reduce the risk of ectasia, since it results in a thicker residual stromal bed, PRK also increases the risk of corneal haze developing in individuals with high myopia.6 LASIK still remains the preferred treatment for high myopes despite these issues.

Practitioners should also pay attention to the preoperative keratometry readings of high myopes—for each diopter reduction in spectacle myopia, the cornea is flattened by about 0.75D, with particularly excessive flattening leading to the onset of aberrations such as spherical aberration or coma. Though well studied in the literature, there’s no consensus on the minimum recommended postoperative keratometry measurements—proposed minimum limits range from 33D to 39D. The topic warrants greater scrutiny and consideration.

| The Court of Public Opinion Most debates about medical and surgical procedures remain within the professional sphere. Not so with refractive surgery. Our internal discussions and concerns have long since spilled over into the lay media, with Morris Waxler, former FDA chair of ophthalmic devices—and one of today’s most vocal critics of LASIK—speaking on the limitations of the data used as the basis for the treatment’s approval in 1998.10 His recent speeches have led to public disagreements, with his supporters on one side aligned against the FDA and various ophthalmology organizations on the other. As these feuds have been covered by popular media outlets, patients may mention them in the exam room. Regardless of which side a practitioner may stand on for any given issue, it is helpful to be aware of these ongoing conversations so that we can continue to be educators and advocates for all patients who enter the clinic. |

In considering, for instance, a 34-year-old lifetime spectacle wearer who presents for a LASIK consultation, three main variables should be examined to determine her LASIK candidacy. Manifest refraction reveals 7D of myopia in each eye, central corneal thickness is 590μm and keratometry readings are 40D. Additionally, her ocular health is suitable in both eyes. However, her attending practitioner should consider the following:

Postoperative corneal thickness. Based on the formula above, it can be estimated that this patient’s post-op RSB thickness following LASIK would be: 590μm - 100μm - (15μm x 7D) = 385μm. This results in an adequate post-surgical corneal stromal bed thickness, so she would therefore qualify to undergo LASIK.

Percent tissue ablation. The PTA value for this patient can also be calculated as (100μm + 105μm) / 590μm = 34.7%. Since this result is less than the proposed threshold of 40%, she also meets this qualification for the procedure.

Postoperative keratometry reading. Keeping in mind that 0.75D of corneal flattening occurs per diopter of myopia, her postop K can be calculated to be 40D - (7D x 0.75) = 34.75D. The estimated postsurgical corneal steepness of just under 35D in this patient is within the gray area between acceptable and inadvisable. Counseling this patient that she is a fair candidate to consider LASIK is warranted; however, she should also be made aware of the potential aberration-induced visual disturbances stemming from her flattened postsurgical corneal shape.

4. Hyperopic Regression

Though refractive surgery is most commonly used to treat myopia, it is also effective in managing hyperopia; however, patients who underwent PRK may be at risk for hyperopic regression for six months to one year after the procedure.

Consider a 35-year-old male with 3D of hyperopia in each eye who was referred for PRK. Though initially satisfied with the results, four months following the procedure he began to complain of difficulty viewing computer screens. The attending practitioner found 1.5D of refractive hyperopia present, and the patient requested a surgical enhancement.

A recent study of retreatment to manage hyperopic regression following LASIK or PRK in hyperopic astigmatic eyes found significantly higher levels of hyperopic regression present at six months post-op in eyes treated with PRK vs. LASIK.7 The researchers’ recommendation was to wait at least six to 12 months after the procedure before considering treatment of hyperopic regression in eyes that had initially undergone PRK.7

So, while LASIK has demonstrated good refractive stability in hyperopic eyes, performance of PRK in hyperopic eyes may raise the potential for hyperopic regression for six months to one year postoperatively. Patients who experience this, including the one mentioned here, should wait until stability is demonstrated so that enhancement efforts can be adequately tailored.

5. Post-LASIK Dry Eye

A 23-year-old female presented to the clinic wearing disposable contact lenses and complained of end-of-day dryness while wearing her lenses. She commented that it would be great if she could eliminate the need for contact lens wear with a LASIK procedure. Ocular examination revealed moderate dry eye syndrome and meibomian gland dysfunction; as such, though she is an otherwise excellent candidate for LASIK, the ocular surface disease should be treated prior to surgery.

Several studies cite dry eye syndrome as the most common postoperative complication in refractive surgery patients, possibly due to disruption of the feedback loop between the cornea and the lacrimal glands during surgery.8,9 For instance, corneal nerves can be severed by the flap creation in a LASIK procedure, reducing the capacity for reflex tearing. Patients who have collagen vascular disease may be at a particularly high risk for development of denervation and subsequent dry eye; as such, aggressive treatment of even mild cases of dry eye is recommended. This can be done by the referring optometrist prior to surgery to help the OD and MD alike in counseling the patient about their suitability for surgery.

Since LASIK’s approval by the FDA nearly 20 years ago, the procedure has improved by leaps and bounds. Today, the rate of postoperative complications is lower than ever. Nevertheless, it remains important for optometrists to be aware of current controversies in care and recent advances in pre- and perioperative care of refractive surgery patients. Such clinical know-how will enable a more effective consultation of patients who may be entertaining the idea of undergoing refractive surgery.

Dr. McNulty is in private practice at the Louisville Eye Center in Kentucky, where he practices comprehensive optometry with an emphasis on the fitting of contact lenses for irregular corneas, as well as optometric laser surgery.

Dr. McWherter is a consultative optometrist at Bennett and Bloom Eye Centers in Louisville, KY, and the director of research at the University of Pikeville–Kentucky College of Optometry in Pikeville, KY.

1. Randleman JB, Woodward M, Lynn MJ, Stulting RD. Risk assessment for ectasia after corneal refractive surgery. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:37–50.2. Santhiago MR, Giacomin NT, Smadja D, Bechara SJ. Ectasia risk factors in refractive surgery. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016 Apr 20;10:713-20.

3. Alpins N, Stamatelatos G. Customized photoastigmatic refractive keratectomy using combined topographic and refractive data for myopia and astigmatism in eyes with forme fruste and mild keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33(4):591602.

4. Santhiago MR, Smadja D, Gomes BF, Mello GR, Monteiro ML, Wilson SE, Randleman JB. Association between the percent tissue altered and post-laser in situ keratomileusis ectasia in eyes with normal preoperative topography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014 Jul;158(1):87-95.

5. Schallhorn S, Brown M, Venter J, et al. The role of the mesopic pupil on patient-reported outcomes in young patients With myopia 1 month after wavefront-guided LASIK. J Refract Surg. 2014;30: 159-165.

6. Pietilä J, Mäkinen P, Pajari T, et al. Eight-year follow-up of photorefractive keratectomy for myopia. J Refract Surg. 2004;20:110-5.

7. Frings A, Richard G, Steinberg J, et al. LASIK and PRK in hyperopic astigmatic eyes: is early retreatment advisable? Clin Ophthalmol. 2016 Mar 31;10:565-70.

8. Golas L, Manche EE. Dry eye after laser in situ keratomileusis with femtosecond laser and mechanical keratome. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011 Aug;37(8):1476-80.

9. Shoja MR, Besharati MR. Dry eye after LASIK for myopia: Incidence and risk factors. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2007 Jan-Feb;17(1):1-6.

10. LASIK Newswire. FDAer Who OK’s LASIK Petitions for Revocation. Available at www.lasiknewswire.com/2011/01/fdaer-who-okd-lasik-petitions-for-revocation.html. Accessed July 18, 2016.