|

Of the eye findings optometrists encounter, the one that tends to cause the greatest concern is corneal ring infiltration. It is not the ring, however, that raises a red flag. It is what the ring is often associated with: Acanthamoeba, one of the most dreaded etiologies of corneal infection. Though infrequently encountered, Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) is known for its destructive path, which can lead to significant vision loss. That said, there are a lot of unique features of AK that cause it to look and behave in ways unique to other microbial sources of infection.

Opportunity Strikes

Acanthamoeba is a genus of free-living protozoan found throughout the world that tends to reside near its food sources. It is not naturally pathologic and only causes disease under opportunistic conditions.1,2 Nearly all adults carry immunoglobulins to Acanthamoeba, and up to 24% of exposed populations have nasal mucosal colonization of the organism despite not having a known infection.3,4

Risky Business

While AK only affects just under one in two million contact lens wearers per year, lens use is the most important risk factor for AK and is associated with nearly 85% of cases.3,5,6 Though the absolute risk is elevated in both soft and rigid gas permeable lens users, the relative risk is almost 9.5 times higher among soft lens wearers; the amoebae seem to adhere more readily to soft lens materials.1,3,5,6

Of the different types of soft lenses, first-generation silicone hydrogels have the highest risk, newer generation and more conventional hydrogels have the next highest risk and daily disposables have the lowest risk.6 Ortho-K has also been linked to a disproportionately high number of AK cases.6

In most cases of AK, lens use combines with other risk factors—poor lens care, contaminated water exposure and corneal epithelium trauma—to cause disease.1,3 Although lens use is the biggest risk factor for AK, it is important to be cognizant of other factors, as 15% of cases develop in non-lens users.

|

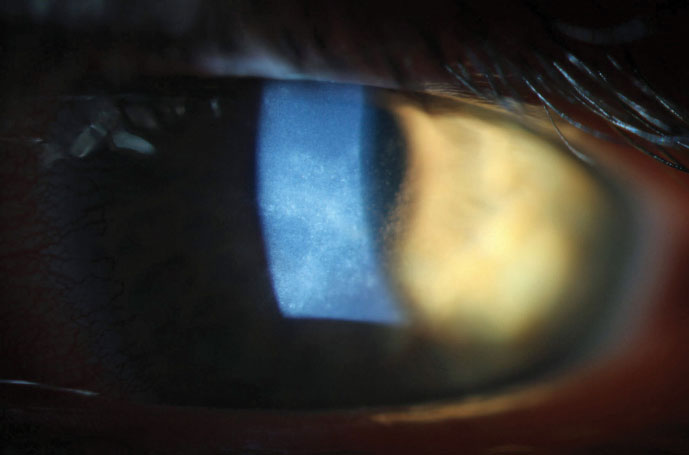

| Due to early diagnosis, this AK patient was able to make a full visual recovery. |

AK Takes its Course

The prognosis for AK varies dramatically depending on the stage at which it is caught; diagnosing the disease early is crucial. While the history you gather from an AK patient is often indistinguishable from that of a bacterial or fungal keratitis patient, the initial clinical picture of AK looks distinctly different than those of other forms of MK.

While we essentially need some degree of ulcerated stromal infiltration to guide suspicion of MK, the same is not true for AK. Instead, early AK is characterized by irregular, well-demarked zones of cystic epitheliopathy, which are generally lightly infiltrated and non-ulcerated. These zones are thought to be superficial tracks caused by motile protozoans as they move through the superficial cornea. The lesions may be dendriform in shape and, as such, are often misdiagnosed as herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis. Any epithelial irregularity diagnosed as HSV keratitis that does not respond to treatment in two weeks should be reconsidered for AK.1,3,4,6

Another early finding of AK is stromal perineuritis, which is nearly pathognomonic. While rare, Psuedomonas and Mycobacterium leprae can also cause perineuritis, but AK is far more likely to produce this finding; perineuritis develops in nearly 63% of AK cases.5 Perinueritis is thought to represent active protist movement along corneal nerves with subsequent infiltration of polymorphonuclear cells around the nerves and may be the cause of the severe pain classically associated with AK. The association of pain greater than the clinical picture indicates with AK, however, is really only applicable in the early stages of the disease when infiltration is mild and ulceration is usually absent, but inflammation of cornea nerves is capable of producing intense pain. By the later stages of AK, when ulceration is typically present, the eye looks like it should hurt and usually does, though patients may develop a degree of neurotrophy as a result of perineural inflammation.5

Due to irregular and localized epitheliopathy, greater pain than the clinical picture indicates and perineural inflammation generally without stromal infiltration and ulceration, early AK should not be mistaken for other forms of MK. Only when AK is caught at this stage can we dramatically alter the outcome with medical intervention. Effectively treating early AK with therapy can completely clear the disease and restore vision without leaving a scar.

Owing to isolate and individual immune differences, there is no exact timeline for AK progression. By the end of the first month, however, findings typically begin to change. Ring infiltration, a late presenting sign of AK, becomes increasingly common and, in most cases, manifests as a ring ulcer—meaning the lesion has an epithelial defect—typically centered on the corneal apex with the area of densest infiltration located along its edges. Though there are other causes of ring infiltration—gram-negative bacteria, fungal corneal ulcers, herpes and anesthetic abuse—and there is no explanation for why AK causes apical ring ulcers, they are 10 times more likely to develop in AK cases than in others.7 It is worth noting that AK-related ring ulcers are different than non-ulcerated ring infiltrates, which are generally not apical or ulcerated, are associated with viral keratitis and carry a relatively good prognosis when not caused by AK.

The Treatment Ladder

Though corneal scrapings can be ordered for AK, my facility sends all suspected AK cases to teaching hospitals for confocal microscopies, which can non-invasively confirm the condition. These centers also initiate therapy as soon as possible, usually the same day. While clinicians can order effective anti-amoebic therapy through compounding pharmacies, it often takes one to two days for patients to receive therapeutic treatment.

Because AK takes on two distinct forms during its life cycle, medical treatment should include both amoebicidal and cysticidal medications and be capable of killing both the amoeba and the cyst. Of the medications currently used to treat AK, polyhexamethylene biguanide 0.02% and chlorhexidine 0.02% (biguanides and cationic antiseptics) are the most successful, with dosed concentrations being 100 times greater than the minimum cysticidal concentration.8 Both, however, are unavailable at commercial pharmacies in the United States and must be obtained from compounding pharmacies.

While not first-line therapies, members of the diamidine family of medications, Brolene (propamidine isethionate 0.1%, May and Baker) and Desomedine (hexamidine 0.1%, Chauvin), also show fairly good efficacy in AK treatment. Diamidines are well-tolerated and not overly toxic, but due to the chronicity of treatment, propamidine can lead to a medicamentosa response.5,8 Obtaining these medications is also a hurdle, as neither is available in the United States. Propamidine can be purchased over the counter in the United Kingdom and online. Though diamidines are easier to acquire given their online availability, they are not strong enough to be considered for monotherapy.

In the later stages of AK, our ability to dramatically alter the course of the disease is limited; sterilizing the eye for subsequent surgery is generally the only option. Regardless of its source, I have never seen a ring ulcer heal without needing a keratoplasty to remove the resultant scar. While the prognosis of therapeutic keratoplasty in eyes with active AK is poor and is associated with a high risk of recurrence, penetrating keratoplasties and deep anterior lamellar keratoplasties have good outcomes when treating corneal scarring and irregularity in eyes with definitively cleared infection and resolved inflammation.1,3,5,8

As with most pathologies, the earlier AK is detected, the better the outcome. However, AK can easily be mistaken for other forms of MK, often resulting in misdiagnosis. This is why it is important to provide care when AK is most recognizable in its earliest stages to avoid sight-threatening implications and preserve visual function before the disease escalates to a severe form of keratitis.

1. Illingworth CD, Cook SD. Acanthamoeba keratitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;42(6):493-508. 2. Berra M, Galperín G, Boscaro G, et al. Treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis by corneal cross-linking. Cornea. 2013;32(2):174-8. 3. Alizadeh H, Niederkorn JY, McCulley JP. Acanthamoeba keratitis. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, eds. Cornea. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2004:1043-74. 4. Clarke B, Sinha A, Parmar DN, et al. Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. J Ophthalmol. 2012;2012:484892. 5. Dart JK, Saw VP, Kilvington S. Acanthamoeba keratitis: diagnosis and treatment update 2009. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(4):487-99. 6. Hammersmith KM. Diagnosis and management of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17(4):327-31. 7. Mascarenhas J, Lalitha P, Prajna NV, et al. Acanthamoeba, fungal and bacterial keratitis: a comparison of risk factors and clinical features. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(1):56-62. 8. Lindquist TD. Treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea. 1998;17(1):11-6. |