|  |

In the middle of the fitting process, you may find one lens choice is no longer working and switch gears to a different modality. Corneal changes over time may mean a lens that once looked perfect no longer gives the patient the desired vision, comfort or fit. Optimal corneal health is often a priority when choosing a design for the compromised eye; however, there are also considerations related to patient handling, wearing schedule and lens longevity. Sometimes, it is best to just start simple with a corneal gas permeable (GP) lens, which can offer excellent performance with streamlined fitting and ease of handling.

Advantages

In the irregular cornea, pursuing a small-diameter corneal GP lens allows for more movement on the eye while blinking, creating an active tear pump.1 The tear turnover rate with a well-fitting GP lens exceeds the rate of other lens types (approximately five minutes for a GP lens vs. 30 minutes for a soft lens).2,3 Tear turnover can facilitate the delivery of oxygenated tears to the compromised cornea but also reduces post-lens debris as metabolic byproducts stagnate between the lens and the cornea.3 The high oxygen permeability attainable with GP materials can allow for optimal physiology and prevent hypoxic complications, especially in post-transplant eyes.

|

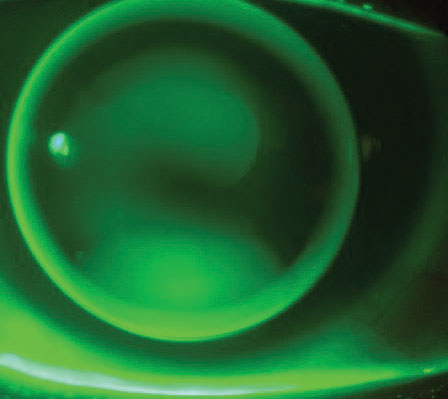

| Corneal lens displaying feather apical touch with divided support in a mild keratoconic eye. Click image to enlarge. |

GP lens materials are durable, reducing the fear of developing defects, such as a rip or tear during the handling process. They also can provide superior optics to soft contact lenses due to material characteristics in conjunction with good stability and centration over the pupil.4 GP lenses are relatively easy and inexpensive to manufacture. They can arrive in your office quickly after being ordered, and patients can obtain replacement lenses when needed. In fact, recommend all patients order a spare pair of lenses upon completion of their GP fit if their best-corrected acuity with spectacles is poor, if there is a possibility of high ametropia or anisometropia if a lens is lost, if they have high-level visual needs or if they operate a motor vehicle—so pretty much everyone!

Fitting a corneal GP lens also leaves the practitioner the option of using a piggyback system to improve centration or stability of the lens system when indicated. Use this option with an existing GP lens or during the course of a new fit.

Disadvantages

Practitioners can easily overcome some of the barriers that they find when fitting corneal GPs.1,5 Concern over poor initial comfort and difficulty with adaptation can be mitigated with a confident GP lens recommendation, use of the proper language (i.e., “lens awareness” instead of “discomfort”) and employing topical anesthetic during the initial fitting process.1

In the post-surgical cornea, sensitivity is often reduced in the first few years after surgery, meaning lens awareness is less of a concern.6,7 There is the potential for instability, i.e., the lens could dislodge or shift off the irregular cornea, but this can hopefully be minimized with appropriate lens modifications during the fitting process in conjunction with patient education on lens handling. Making the switch to a reverse geometry lens design may also improve lens fit and centration in a corneal GP on an oblate eye. Any debris under the lens can be minimized by adding coatings, making changes in lens material, and paying attention to lid hygiene, lens care and handling processes.

Case One

A 38-year-old male patient presented for a contact lens fitting, having been newly diagnosed with keratoconus. He had never worn contact lenses before. As an emergency room physician, he often works long hours and needs to sleep in his lenses on occasion. OD slit lamp evaluation showed mild apical corneal steepening but minimal thinning and no striae or scarring. OS slit lamp evaluation showed moderate apical steepening and thinning and central Vogt striae. Using a diagnostic fitting set in-office achieved a textbook keratoconic lens fit in each eye, and the patient was successful after dispense, training and follow-up visit.

In patients with keratoconus, GP lens materials tend to provide the best visual performance, so avoiding a soft contact lens is sensible in a patient whose vocation demands excellent vision.4 Since this patient may also potentially sleep in his lenses while on shift, we shied away from fitting a large diameter scleral GP lens and made sure the corneal lens material was highly permeable to oxygen. In cases of mild keratoconus, fitting a corneal GP is fairly straightforward—aim for feather apical touch and adequate edge lift in combination with lens movement upon the blink. You can follow the fitting guide for a keratoconic GP lens design from your laboratory of choice or call the lab’s consultation line for fitting assistance. Use of a wratten filter during the fitting process can also help highlight areas of lens touch or pooling.

|

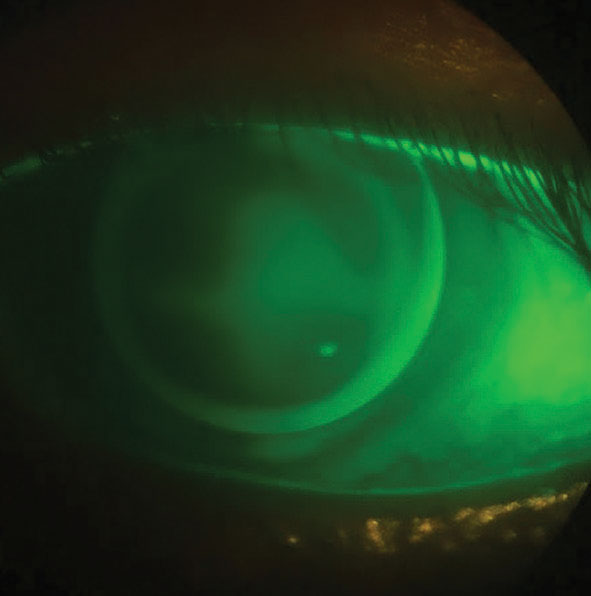

| GP lens fit on a patient with corneal scarring. Click image to enlarge. |

Case Two

A 44-year-old male patient presents for a contact lens fitting due to regression after LASIK OU 15 years prior. He was undergoing treatment for ocular surface disease and experiencing end-of-day-dryness and frequent lens tears with his habitual monthly replacement soft toric lenses. A refit into a daily disposable soft toric resolved the lens handling issue, but he still experienced symptoms of dryness and only achieved 20/30 vision OD and 20/25 vision OS. The lenses were unstable on his oblate cornea, rotating unpredictably while he blinked throughout the day.

As a baseball coach, the patient longed for not only good vision but also the ability to wear sunglasses while out on the field. Having worn GP lenses in the past, he expressed a desire to return to their stability and durability. When fit with a 10.5mm diameter, reverse-geometry corneal GP lens, the patient was able to achieve 20/20 vision in each eye with good comfort. We discussed the possibility of incorporating multifocal optics into his lenses in the future when he has a greater need for presbyopic correction.

Case Three

A 60-year-old Caucasian male who had a penetrating injury OS at age 10 is now aphakic with a central corneal scar. He presents for contact lens fitting stating he “hasn’t seen out of that eye in years.” Manifest refraction of OS +11.25 -1.25 x 120 allowed for 20/40 vision, and a corneal GP lens centered well over the irregularity with some mild central pooling gave the same acuity improvement. We prescribed the patient full-time wear polycarbonate over-glasses for protection of the right eye and to incorporate the +2.50D add power necessary for best near vision.

No matter the disease state you encounter, there is a distinct possibility that a corneal GP lens is an option for your patient. When you consider these lenses, you can be confident they will deliver excellent visual acuity, corneal physiology, ease of handling and lens durability all while taking less chair time than some other modalities might require. The improvement in visual acuity achieved over soft lenses often negates any drawbacks you may encounter in the fitting process of a corneal GP lens design for patients with irregular corneal conditions, so don’t hesitate to prescribe these lenses despite the allure of more complex designs. Sometimes the simplest option really is the best option.

1. Bennett ES, Sorbara L, Kojima R. Gas-permeable lens design, fitting and evaluation. In: Bennett ES, Henry VA. Clinical manual of contact lenses. 4th Ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2014. 2. Holden, BA, Sweeney DF, La Hood D, Kenyon E. Corneal deswelling following overnight wear of rigid and gydrogel contact lenses. Curr Eye Res. 1988;7(1):49-53. 3. Muntz A, Subbaraman LN, Sorbara L, Jones L. Tear exchange and contact lenses: a review. J Optom. 2015;8(1):2-11. 4. Griffiths M, Zahner K, Collins M, Carney L. Masking of irregular corneal topography with contact lenses. CLAO. 1998;24(2):76-81. 5. Quinn TG. GP versus soft lenses: Is one safer? CL Spectrum. 2012;27(4):34–9,58. 6. Krachmer J, Palay D. Chapter 21: Penetrating keratoplasty. In: Cornea atlas. 3rd Ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. 2013. 7. Steele C. Chapter 22: Post-keratoplasty contact lens fitting. In: Phillips AJ, Speedwell L. Contact lenses. 5th Ed. Waltham, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann Elsevier. 2007. |