|  |

Despite these advances, patient satisfaction may wane over time. Accommodative and lenticular changes may cause refractive error shifts, requiring vision correction. Worse complications—including severe dry eye, corneal scarring and other corneal irregularities—can dramatically impact vision quality. Although patients may hesitate to pursue contact lenses, gas permeable (GP) lenses are often the best choice to meet their visual needs.

|

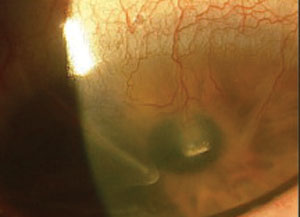

| A 16-cut RK. |

The National Eye Institute’s 1980 Prospective Evaluation of Radial Keratotomy (PERK) study found that, after one year, 60% of eyes that underwent radial keratotomy (RK) were within +/- 1.00D of emmetropia, with 78% having uncorrected visual acuities (VA) of 20/40 or better.1 In 1994, the 10-year study results found that, of the 88% of patients who returned, 60% were still within 1.00D of emmetropia, but 43% of eyes had a hyperopic shift of 1.00D or more.2

Patients who underwent RK in the study are currently 40 or older. In addition to significant hyperopic shifts, they are now presbyopic and require full-time vision correction for both distance and near. Some are now ready for cataract surgery. Radial incisions weaken the overall stability of the cornea, creating diurnal variations in intraocular pressure, which contribute to corneal curvature and VA changes.3

The further incisions extend into the clear cornea, the greater the risk of instability.2 In addition, research shows irregular astigmatism is a likely complication around the incisions.4 These patients not only are more likely to experience a hyperopic shift, but will also complain of distortion, glare and halos at night and overall poor quality of vision.2,5 Other adverse events such as neovascularization, split incisions, scarring and inclusion cysts may further complicate the situation.

Post-LASIK Challenges

Although laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) is the most common elective surgical procedure in the world today, it has complications.6 Patients may struggle with severe dry eye, decreased quality of vision and glare or starbursts at night.7 One visually devastating complication is post-LASIK ectasia, even though research reports the incidence ranging from only 0.2 to 0.6%.8,9 GP lenses are commonly used to correct irregular astigmatism induced by ectasia.

|

| RK incisions with neovascularization and opacity. |

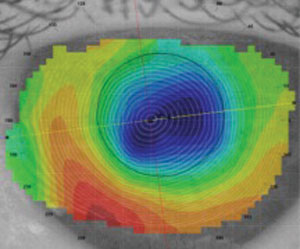

GP lenses are a good option for post-surgical eyes in need of further vision correction. When fitting such patients with lenses, clinicians can use a corneal topographer to assess corneal shape and help determine appropriate lens design. RK patients have flatter central corneas due to the radial cuts extending toward the central cornea, in addition to a varying degree of mid-peripheral steepening (knee effect) and irregularity. Meanwhile, the non-ectatic myopic LASIK patient will have a defined ablation zone within the central cornea.

Both types of post-surgical eyes can be described as oblate in shape, with a flatter central curvature and steeper mid-periphery. If a flat base curve (BC) is chosen to match the central cornea, it may cause excessive edge lift or corneal molding. A steeper BC may fit the mid-periphery better, but could result in central bubbles or peripheral seal-off.

To properly fit the entire cornea, reverse geometry GP lenses are often the best choice for alignment. For GP intolerant patients or difficult fits, hybrid or scleral lenses can also be used to vault the cornea entirely.

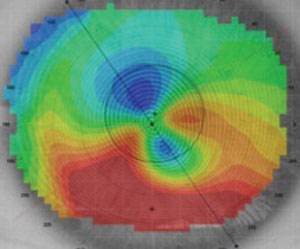

Post-hyperopic LASIK patients, however, have steeper central corneas more characteristic of a prolate shape. While aspheric GPs often provide acceptable fits, keratoconic lens designs can also be used. If ectasia is suspected but not clearly evident in the slit lamp, corneal topography will reveal it. As with keratoconus, corneal steepening typically occurs inferiorly. Centration can be difficult to achieve, so larger diameter GPs, hybrids or scleral lenses that vault the entire cornea are ideal.

|

| Post-RK axial map. |

GP lenses for the oblate cornea can be fit both diagnostically and empirically. As with any GP lens, the main goal is good centration and sodium fluorescein alignment. In addition to diameter, which typically ranges from 10mm to 11mm, reverse geometry lenses have two curves that control the lens fit. First, the BC aligns the lens with the central cornea. The second curve moving outside of the optic zone is the reverse curve, commonly referred to as the fitting curve. Steepening or flattening this curve can manipulate the sagittal depth to align with the steeper mid-peripheral cornea.

When choosing the initial lens, practitioners should follow the lens’s fitting guide. If the curves must be adjusted, avoid changing both the BC and the reverse curve simultaneously. Once the central and mid-peripheral cornea is aligned, the peripheral edge can be refined.

In the event that a diagnostic set is not available, reverse geometry lenses can be designed empirically using corneal topography and refractive data. Several lens designs have

|

| Fig. 4. Post-LASIK ectasia axial map. |

Beyond GPs

Hybrid and scleral lenses are becoming the first-line choice because of their wide variety of indications. Their ability to vault the cornea can mask larger amounts of irregularity for oblate and ectatic corneas alike. Both now have expanded prolate and oblate shape designs. Their larger diameter and on-eye stability can improve comfort for many patients. Research proves scleral lenses to be therapeutic for ocular surface disease, which is concomitant in many post-refractive surgery patients.

Patient Expectations

One of the most important aspects of fitting post-refractive surgery patients is evaluating and managing expectations. Some successful patients have regressed over time, leading to decreased visual acuity and quality. They often desire better vision without spectacles. While their goals may be achieved, especially with newer multifocal options, the fitting process can be challenging. Proper patient education about fitting process and cost is essential.

Patients who have struggled with less-than-ideal outcomes from RK or post-LASIK may present frustrated and angry at their current situation; but the significant vision improvements GP lenses can provide often leave them ecstatic. No matter which patient is in your chair, you have an arsenal of lenses to meet their needs.

1. Waring GO, Lynn MJ, Gelender H, et.al. Results of the prospective evaluation of radial keratotomy (PERK) study one year after surgery. Ophthalmology. 1985 Feb;92(2):177-98, 307.

2. Waring GO 3rd, Lynn MJ, McDonnell PJ. Results of the prospective evaluation of radial keratotomy (PERK) study 10 years after surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994 Oct;112(10):1298-1308.

3. Kemp JR, Martinex CE, Klyce SD, et.al. Diurnal fluctuations in corneal topography 10 years after radial keratotomy in the porspective evaluation of radial keratotomy study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1999 Jul;25(7):904-10.

4. Rashid ER, Waring GO. Complications of radial and transverse keratotomy. Surv Ophthalmol. 1989 Sep-Oct;34(2):73-106.

5. Grimmett MR, Holland EJ. Complications of small clear-zone radial keratotomy. Ophthalmology. 1996 Sep;103(9):1348-56.

6. Reinstien DZ, Archer TJ, Gobbe M. The history of LASIK. J Refract Surg. 2012;28(4):291-8.

7. Eydelman M, Hilmantel G, Tarver ME, . Symptoms and atisfaction of atients in the atient-eported utcomes ith aser n itu eratomileusis (PROWL) tudies. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(1):13-22.

8. Rad, A.S., Jabbarvand, M., Saifi, N. Progressive keratectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis. J Refract Surg. 2004 Sep;20(5):S718–S722.

9. Pallikaris IG, Kymionis GD, Astyrakakis NI. Corneal ectasia induced by laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27(11):1796-1802.