|

|

A 74-year-old man was sent in for an emergency evaluation of a corneal disorder. He was not experiencing any acute distress or pain; however, he stated that he had been dealing with poor, blurry vision in his left eye for the previous three weeks. As he had been traveling over that timeframe, a non-local facility provided most of his care. He estimated he had been seen four times by an optometrist who had placed him on various combinations of antibiotics and steroids to no avail. He only recently returned home, where his primary optometrist saw him twice and ultimately referred him to us.

Examination

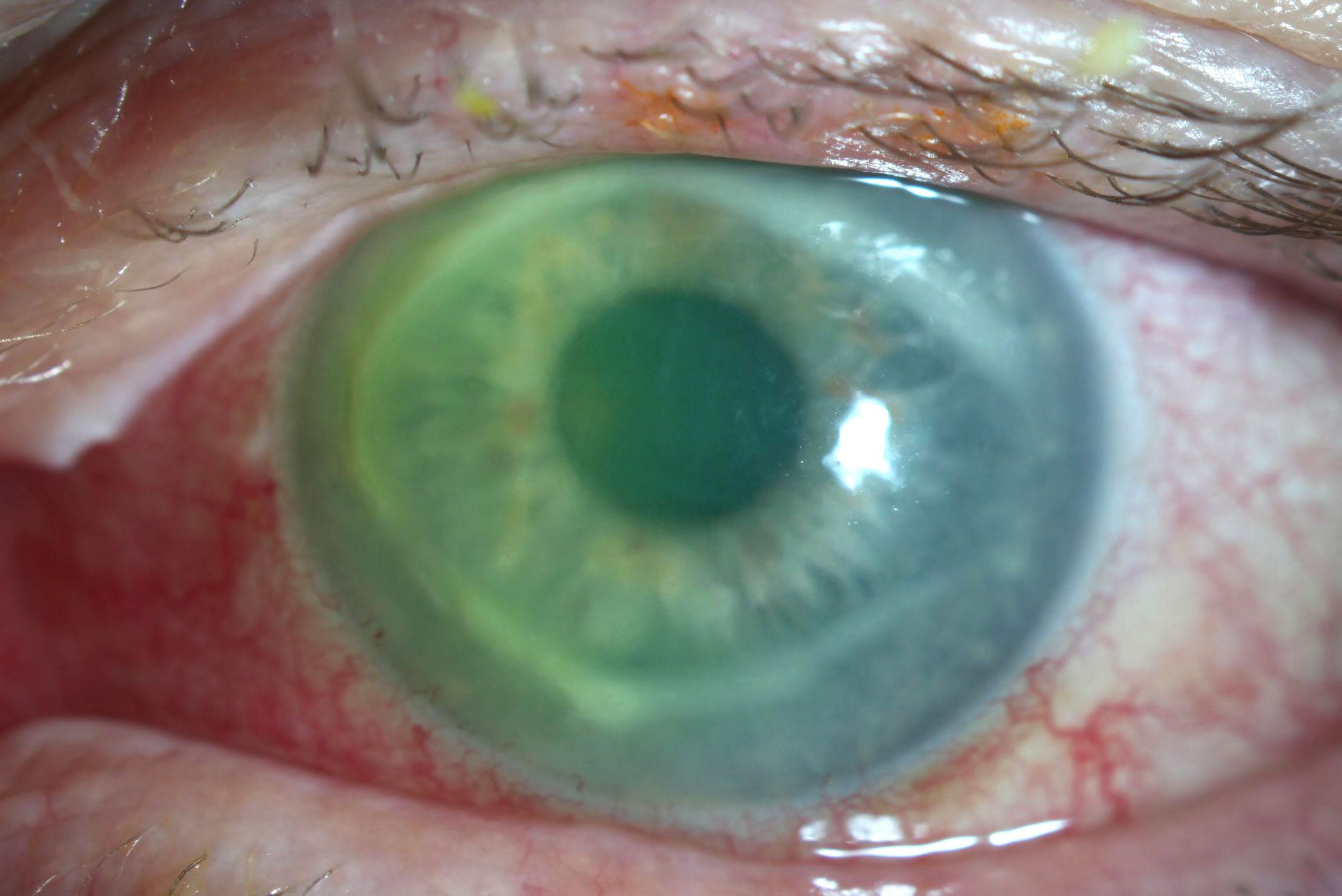

At the time of the patient’s initial exam at our facility, he was on moxifloxacin QID and prednisolone acetate Q2H OS. Habitual glasses correction yielded 20/25 vision OD and 20/400 OS. His pupils were normal and reactive without an afferent pupillary defect. Slit lamp exam was unremarkable OD. His left eye showed 2+ to 3+ injection, with the greatest area of involvement around the limbal region. The cornea showed a large apical ring infiltrate that was dense and well-defined. The central corneal had 2+ central edema within the margins of the ring. Fluorescein staining showed partial epithelial breakdown over the ring. Centrally, the epithelium was intact. The anterior chamber showed modest flare, with no cell or hypopyon in sight. The iris had a small stromal hemorrhage at five o’clock.

We tested the patient’s corneal sensation with dental floss. He had slight sensitivity to touch in all quadrants OS compared with his fellow eye, which exhibited a hypersensitive response. This illustrates the importance of testing both eyes when establishing neurotrophy.

After examining the patient, we questioned him more closely. He denied contact lens use, had not experienced any trauma to the eye, didn’t splash tap water in his eyes and had not used a swimming pool or hot tub recently. He had no previous history of eye problems aside from glasses and had never had an episode like this before. His history was negative for any known autoimmune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis and polyangiitis with granulomatosis. He further denied any history of cold sores or previous issues with his eye that might suggest herpes simplex. He did, however, have a positive response to questioning about shingles. He described an episode two months earlier where he developed a small, crusted lesion on the left side of his forehead. He thought it was a spider bite and went to Urgent Care, where the staff suspected a mild shingles flareup. He took a course of valacyclovir and oral antibiotics, and the lesion resolved.

|

The patient’s eye at presentation shows 2+ to 3+ injection, a dense apical ring and central stromal edema. Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

Apical corneal ring infiltrates are an interesting phenomenon in ocular disease. These entities are most frequently seen in late-stage Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) and are associated with a poorer medical prognosis. Patients usually require a transplant to clear the resultant scars. Despite this association, diagnosing all apical rings as AK is a poor strategy, as they may also be caused by bacteria, fungi, viruses, protozoa, autoimmune disease or corneal foreign bodies, all of which have their own distinct treatments and prognoses. Apical rings may even be confused with corneal neurotrophic ulcers. Therefore, it is important to understand how these different etiologies of rings vary from one source to the next and proceed accordingly with the clinical exam and specific history. This enables the clinician to navigate this differential of multiple severe pathologies with more confidence.

While the clinical appearance of this pathology was most in line with AK, the underlying diagnosis required us to look at the clinical picture in combination with the history. And in this particular case, there were no supportive historic elements that pointed toward AK. The patient was not a contact lens wearer, had no history of ocular trauma and denied even remote use of a hot tub or swimming pool. He lacked all identifiable historic risk factors for AK, making this diagnosis less of a possibility but not completely ruling it out. Similarly, the patient lacked all risk factors for other forms of microbial keratitis.

The patient’s symptoms also suggested an alternate cause. Again, his sole concern was his reduced vision, and he had no discomfort. While minimal and even total lack of pain has been reported in AK cases, it’s the exception, not the rule, in a condition where marked pain is the norm.

|

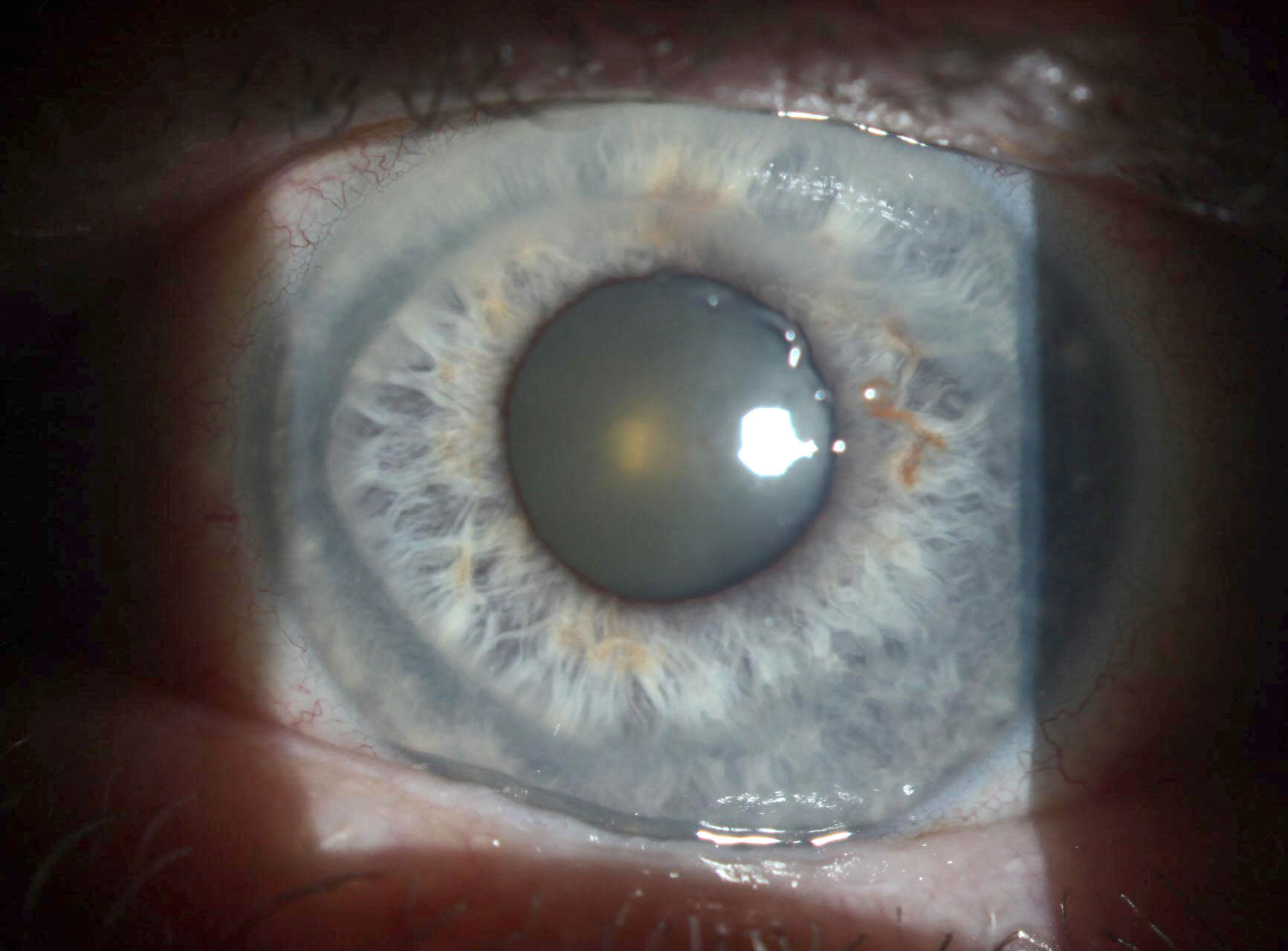

Upon resolving, the inactive ring also thinned. Click image to enlarge. |

Given the patient’s full clinical picture, his reduced corneal sensation—which while more suggestive of herpes can also be present in AK—the lack of identifiable risk factors for AK or other forms of microbial keratitis and the history of a possible recent bout of shingles involving the left side of the face, we decided we were most likely dealing with an atypical case of herpes zoster ophthalmicus serpiginous keratitis.

We educated the patient on the severity of the pathology and potential for ongoing vision loss. For treatment, we reduced his steroid dosage to QD, not wanting to fully discontinue therapy immediately for fear of creating a massive rebound inflammation. We also placed him on both Zirgan (ganciclovir ophthalmic gel, Bausch + Lomb), which has theoretic efficacy against the varicella zoster virus, five times daily and valacyclovir 1000mg TID.

Given the abnormal features of this disease presentation, we had the patient undergo blood work to test for ANCA, Rf, HSV and VZV antibodies. He was only positive for VZV antibodies.

If the patient had failed to respond to our therapy promptly, we would have sent him for confocal microscopy imaging. Fortunately, he responded positively to treatment, and within a week’s time, the ring was re-epithelialized and inactive. Unfortunately, the ring thinned as it resolved, despite the addition of doxycycline to our regimen, resulting in an irregular and steep central cornea. Though the patient undoubtedly improved since presentation, his best spectacle-corrected acuity remained reduced at 20/50.

This case illustrates the importance of ensuring the clinical picture and case history all fit together prior to rushing to a diagnosis based purely on a suggestive, but non-pathognomonic, finding.