|

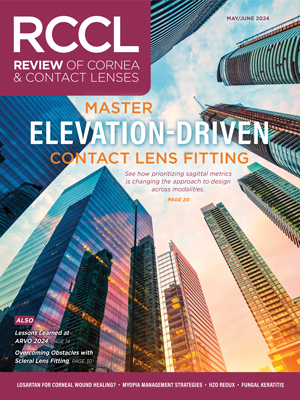

An 88-year-old female presented for an emergency visit complaining of irritation to her right eye. Her uncorrected acuity was 20/25 OD and 20/25 OS, and she refused intraocular pressure readings. Ocular history was notable for macular drusen in both eyes. Clinical exam revealed trichiasis in the right lower lid with one distinct lash causing irritation to the inferior nasal cornea OD. She had an incomplete blink and conjunctival injection OD. An inferior nasal corneal ulcer with a 1mm x 3mm stromal infiltrate OD was present (Figure 1).

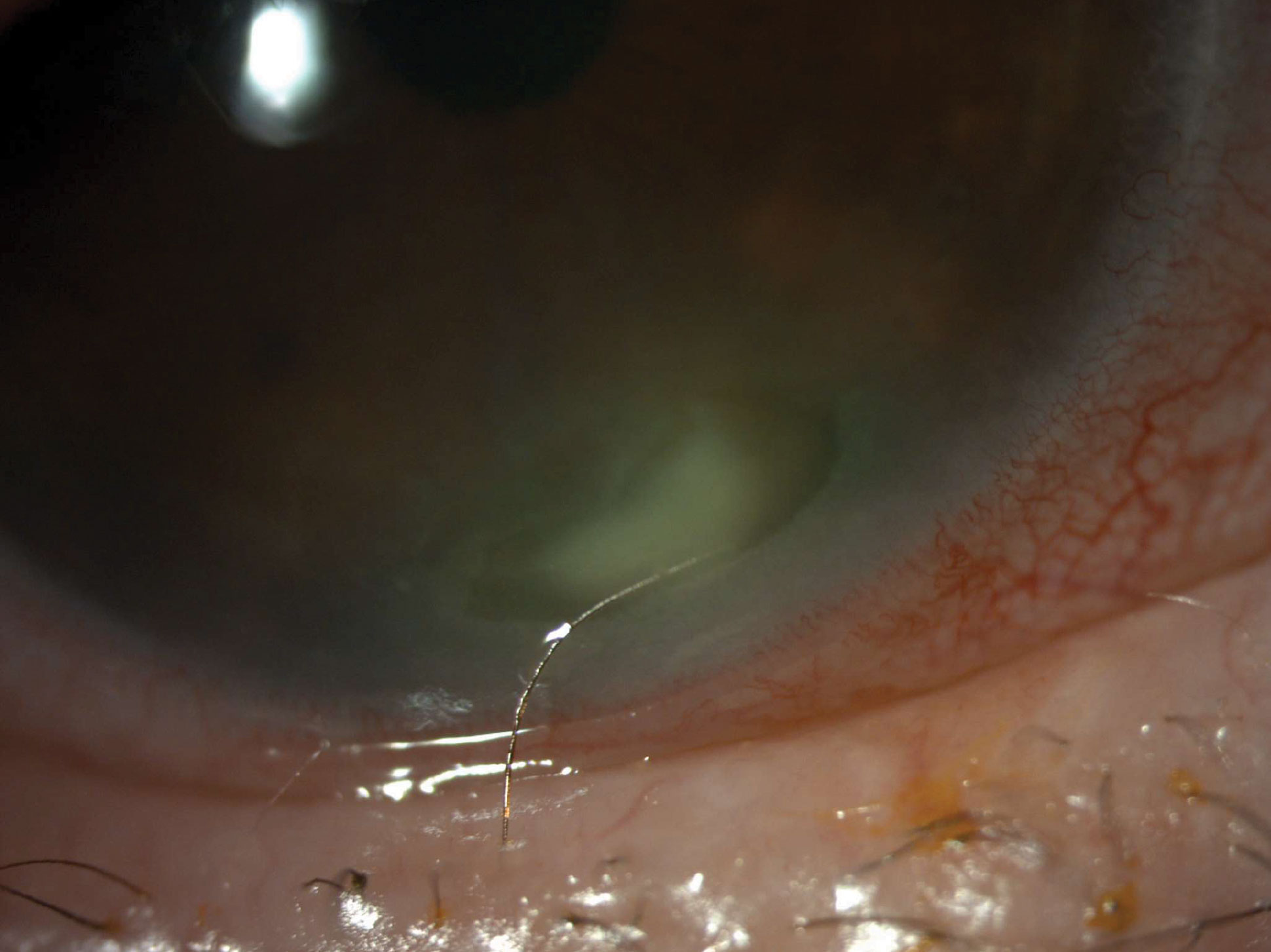

On the initial visit, epilation of the lower right lid lash in question was performed and well-tolerated. A corneal scraping on an agar plate was performed (Figure 2). She was started on moxifloxacin and asked to follow-up in four days.

Within 24 hours, the patient called complaining of pain and worsening of vision and came back to the office. She reported not using moxifloxacin due to burning after instillation. At this visit, results from the culture returned with growth of Moraxella catarrhalis beta-lactamase, which slightly altered the treatment plan. The patient was told to continue moxifloxacin and start polymyxin B/trimethoprim Q1h while awake and erythromycin oph ung to be used at night.

At one-week follow-up, she slowly improved but her vision was still 20/25. The infiltrate further consolidated; however, keratic precipitates were seen and a grade one anterior chamber reaction was present. Due to this change, prednisolone was added to the regimen twice a day, and at the next visit it was increased to four times a day as the keratic precipitates had not resolved.

|

| Fig. 1. Patient at initial presentation with a corneal ulcer and one distinct lash (trichiasis). Click image to enlarge. |

Corneal Ulcers

Around 30,000 cases of microbial keratitis occur annually in the United States, with the majority being bacterial in origin.1,2 Having a plan for how to handle them can be sight-saving for patients.

Signs may include epithelial defects overlying a single stromal infiltrate, indistinct infiltrate edges, corneal edema with white cell infiltration of nearby stroma, an anterior chamber reaction and hypopyon often located in the inferior cornea.2-7 Symptoms can include pain, photophobia, decreased vision, redness and discharge.2,7-9

Once you have made your clinical observation and the differential diagnosis of a bacterial ulcer is under consideration, an even more focused patient history must be obtained. It is imperative to remember the risk factors for bacterial corneal ulcers, including contact lens wear, ocular surface disease, acute corneal trauma and corneal surgery.3 At this point, the decision of whether to culture or not will need to be made, which is multifactorial. If you are in a situation that does not give you the ability to culture, the choice of whether to send it out before starting antibiotics becomes urgent.

|

| Fig. 2. Blood agar culture done with a blade. Click image to enlarge. |

When to Culture

As published by the American Academy of Ophthalmology, the Bacterial Keratitis Preferred Practice Pattern guidelines state that smears or cultures of infectious corneal ulcers are recommended when any of the following circumstances are present: ulcer >2mm and centrally located, significant stromal melting, unresponsive to empiric antibiotic therapy, characteristics suggestive of amoebic, mycobacterial or fungal infection or a history of corneal surgery.7

Even though this patient did not meet any of the criteria, I cultured her for the following reasons: (1) she is an elderly patient who was very difficult to get to come in for an exam, (2) it appeared as though this ulcer had been present for an extended amount of time, (3) she had an incomplete blink causing chronic exposure and (4) I have easily accessible culturing and smear materials at my office.

|

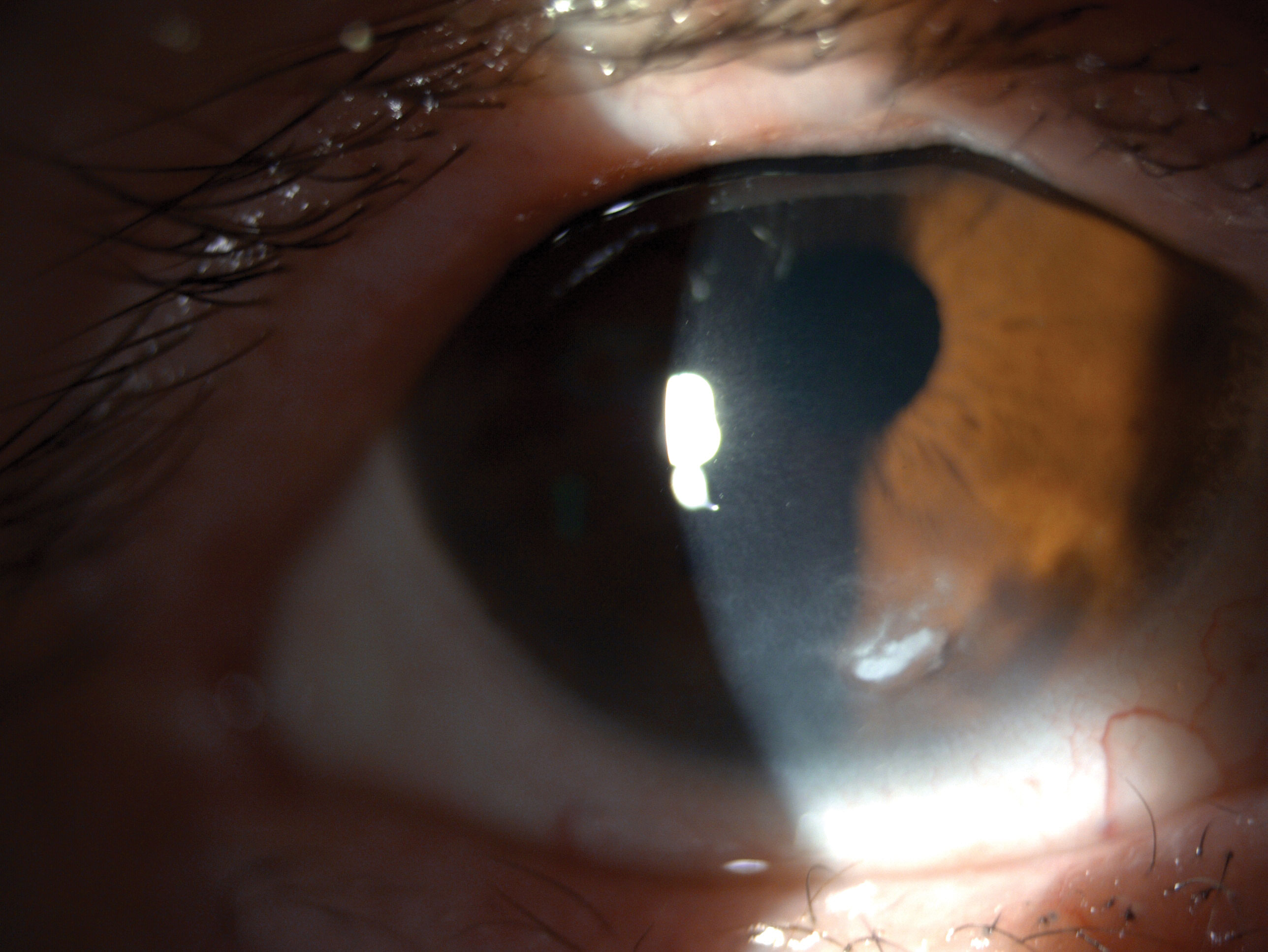

| Fig. 3. Confirmed bacterial corneal ulcer one month after treatment was initiated. Seen here is a condensed and dried up infiltrate. Click image to enlarge. |

Treatment

First-line therapy for infectious ulcers traditionally involves the use of empiric treatment with extended-spectrum topical antibiotics, such as fluoroquinolones.2,4,8-10 As of now, there is no agreed-upon treatment regimen—ciprofloxacin 0.3%, levofloxacin 1.5% and ofloxacin 0.3% are all FDA-approved to treat bacterial keratitis.9 If the ulcer is sight-threatening, accompanied by a hypopyon and/or deep stromal involvement, fortified topical antibiotics are beneficial.

In this case, we started with moxifloxacin. The positive result of Moraxella did alter our treatment and we were able to make this decision faster instead of waiting for a recalcitrant ulcer. The most common causes of bacterial keratitis are Haemophilus influenza, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis.11,12 Moraxella, a gram-negative rod, is not as common. This positive culture led us to add polymyxin B/trimethoprim, an antibiotic drug that is active against a wide variety of gram-positive and gram-negative ophthalmic pathogens. Specifically, polymyxin B is an excellent bactericidal against most gram-negative bacterial species.13

Steroids

The goal of using steroids is to diminish tissue damage from the inflammatory response and reduce stromal melt, neovascularization and scarring. Its use is debated because steroid therapy may delay epithelial healing, leading to stromal thinning and melt.2,8,10 The Steroids for Corneal Ulcers Trial studies have compared clinical outcomes in bacterial keratitis treated with antibiotics and steroids vs. solo antibiotics and found no significant adverse effects when using steroids; some ulcers experienced better visual outcomes at three months.2,14 These studies also found that timing and dosage are important. Patients who started steroids after only two or three days of antibiotic use experienced better visual outcomes, and patients who weren’t started on steroids until later had the same or worse acuity.2,14,15

In our case, steroids were not prescribed initially due to the ulcer location, which was not visually threatening. However, the subsequent presence of keratic precipitates and an anterior chamber reaction altered our treatment regimen, which may ultimately have prevented scaring.

Luckily, the patient gradually improved over a month (Figure 3). The stromal infiltrate continued to consolidate and we considered debriding the infiltrate. This method would be used if improvement had stagnated. Fortunately, she continued to have gradual improvement with the antibiotic and steroid drops.

Whether you see these cases every week or only rarely, you should consider bacterial keratitis in your differential for corneal ulcers. Imaging the ulcer is a great first step in monitoring. Remember that proper identification of the etiology is essential in accurate management. Knowing and understanding the use of adjunctive diagnostic evaluation and treatment—such as culture, fortified antibiotics and steroids—can play an important role in improving visual outcomes.

1. Palioura S, Henry CR, Amescua G, Alfonso EC. Role of steroids in the treatment of bacterial keratitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:179-86. 2. Sherman S, Cherny C. Keeping up with keratitis. Rev Optom. 2021;158(4):62. 3. Bourcier T, Thomas F, Borderie V, et al. Bacterial keratitis: predisposing factors, clinical and microbiological review of 300 cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87(7):834-8. 4. Dalmon C, Porco TC, Lietman TM, et al. The clinical differentiation of bacterial and fungal keratitis: a photographic survey. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(4):1787-91. 5. Mascarenhas J, Lalitha P, Prajna NV, et al. Acanthamoeba, fungal and bacterial keratitis: a comparison of risk factors and clinical features. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(1):56-62. 6. Thomas PA, Leck AK, Myatt M. Characteristic clinical features as an aid to the diagnosis of suppurative keratitis caused by filamentous fungi. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(12):1554-8. 7. Lin A, Rhee MK, Akpek EK, et al. Bacterial keratitis preferred practice pattern. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(1):P1-55. 8. Ni N, Srinivasan M, McLeod SD, et al. Use of adjunctive topical corticosteroids in bacterial keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2016;27(4):353-7. 9. Moshirfar M, Hopping GC, Vaidyanathan U, et al. Biological staining and culturing in infectious keratitis: controversy in clinical utility. Med Hypothesis Discov Innov Ophthalmol. 2019;8(3):145-51. 10. Austin A, Lietman T, Rose-Nussbaumer J. Update on the management of infectious keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(11):1678-89. 11. Teweldemedhin M, Gebreyesus H, Atsbaha AH, et al. Bacterial profile of ocular infections: a systematic review. BMC Ophthalmology. 2017;17:212. 12. Shuja F, Sherman S. Smart strategies on using antibiotics to treat corneal infections. Rev Cornea Contact Lenses. 2019;156(6):18. 13. Melton R, Thomas R. Topical antibiotics. The clinical guide to ophthalmic drugs. Rev Optom. 2009;796(8). 14. Srinivasan M, Mascarenhas J, Rajaraman R, et al. Corticosteroids for bacterial keratitis: the steroids for corneal ulcers trial (SCUT). Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(2):143-50. 15. Ray KJ, Srinivasan M, Mascarenhas J, et al. Early addition of topical corticosteroids in the treatment of bacterial keratitis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(6):737-41. |