|

|

A 17-year-old male was referred for a uveitis evaluation. He’d been seen by his primary OD about four weeks ago, at which time he noted redness and reduced vision. He was diagnosed with iritis and placed on prednisolone acetate 1% QID OU. The patient’s symptoms had subsided to the point where he no longer needed the steroid. After approximately one week, however, his symptoms returned, so he was sent in for evaluation.

Examination

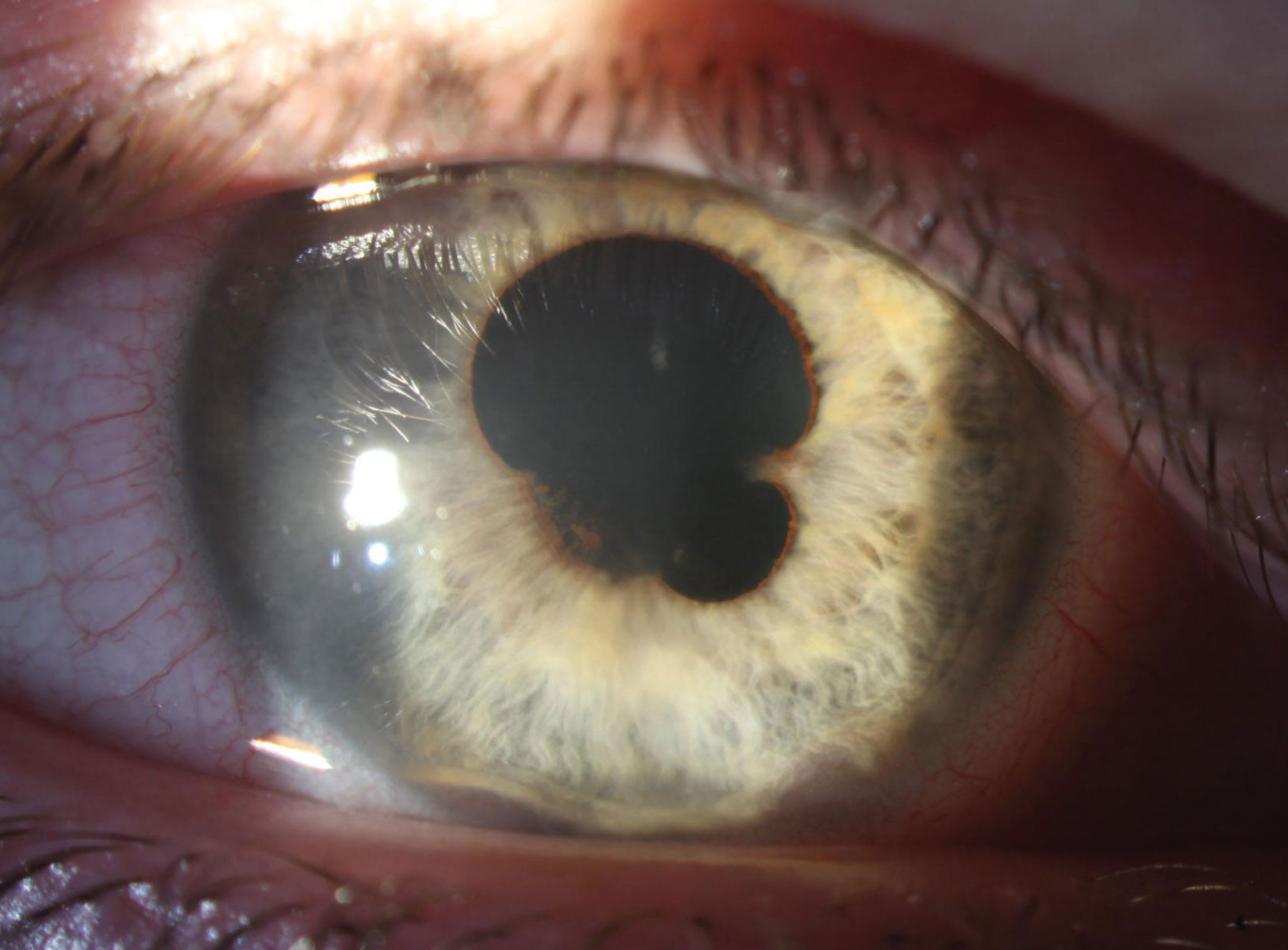

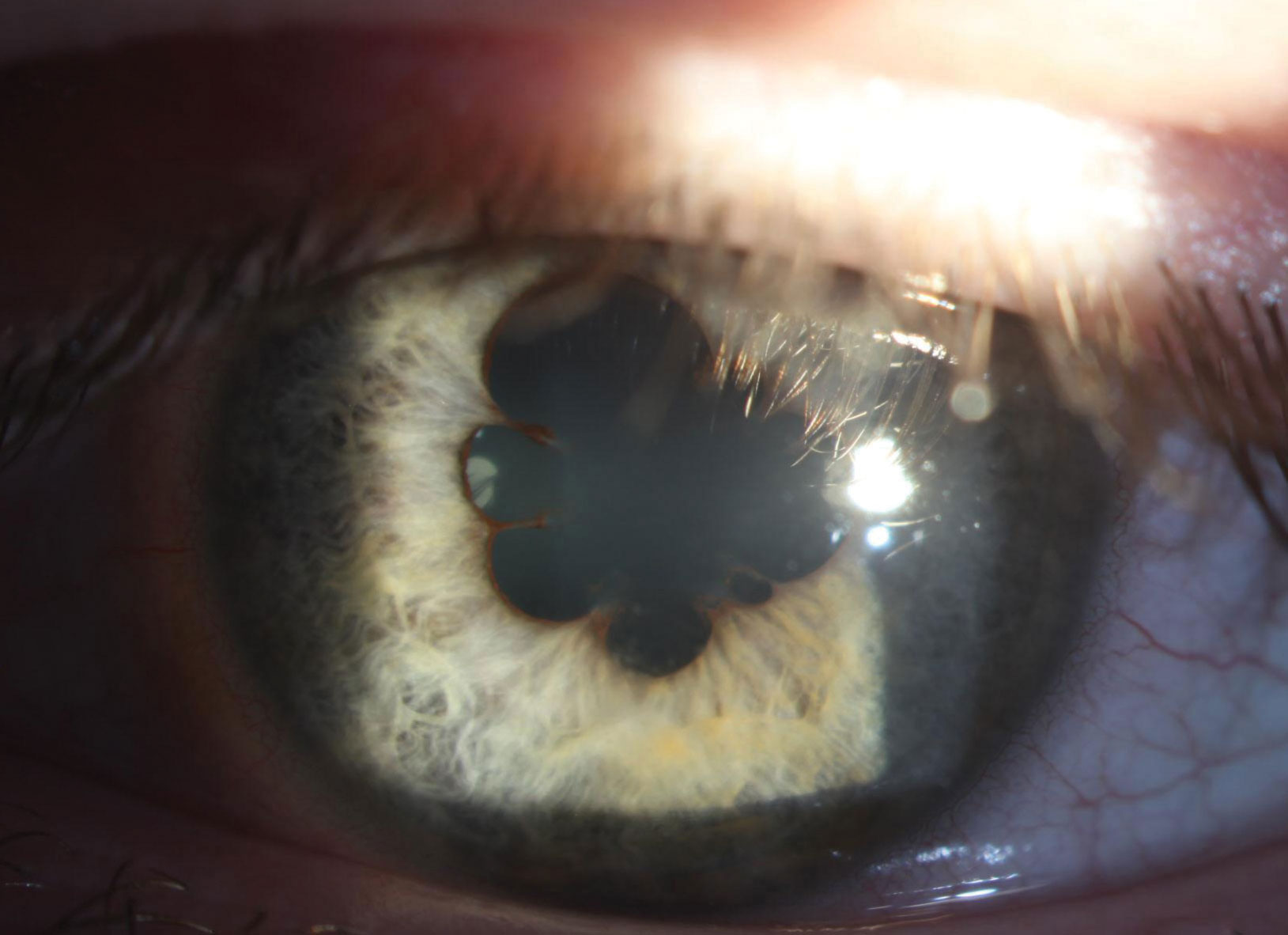

On exam, the patient’s vision was 20/25 OD and 20/20 OS. His pupils were misshapen and minimally reactive. His extraocular muscles were normal, and his confrontation fields were full-to-finger counting. His intraocular pressures were 19mm Hg OD and 23mm Hg OS.

Slit lamp evaluation showed 1+ to 2+ conjunctival injection OU, 2+ fine keratic precipitates with few larger confluences OU and 3+ cell and mild flare in the anterior chamber OU. The patient’s irides had remarkable anterior and posterior synechiae.

Dilated exam showed normal posterior segments, with the exception of some spillover cells in the anterior vitreous.

The patient denied problems with lower back or knee-based pain. He had no unusual skin lesions and didn’t think he reacted abnormally to skin injuries or scratches. He had no history of oral or genital ulcerations and denied difficulty or pain with urination. He had no respiratory issues and denied fevers or night sweats. Other than the bout of strep throat he had developed approximately two months earlier and the short course of oral antibiotics that followed, he was a healthy young man undergoing an episode of iritis.

|

| Broad and extensive posterior synechia are present in the right eye at presentation. Substantial anterior synechia are also apparent at 5 o’clock and 7 o’clock. Click image to enlarge. |

Management

Treating our patient’s ocular pathology was relatively straightforward. We find that our profession is often reluctant to initiate an effective dose of anti-inflammatory therapy and too eager to initiate a taper. The goal of initial therapy is to get inflammation under total control, and in an eye with intense inflammation, this almost always requires Durezol (difluprednate, Novartis). Maintain the effective dose for about a week before making any attempts at a slow taper.

We tend to treat most acute anterior uveitis (AAU) cases as though they are HLA-B27-linked, and we know that the average duration of a flare-up of this type is six to eight weeks. Thus, this is my targeted treatment duration.1

In this instance, we began the patient on Durezol every hour OU and gradually tapered him off over a six-week interval. We maintained him on cycloplegics over the first two weeks of therapy but eliminated these as inflammation came under better control.

|

| In the left eye, 360° of marked posterior synechiae can be seen at presentation. Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

Much of the optometric education on uveitis suggests treating initial episodes and considering systemic testing should the disease recur. However, systemic testing should be conducted as soon as suspicion of an underlying pathology arises.

In this patient’s case, there were clear indicators that his uveitis was caused by systemic pathology, despite his negative review of systems. The indicator was something so mundane that it was hiding in plain sight—his specific classification of uveitis.

It is easy to consider this a case of anterior uveitis or iritis, but only diagnosing to this degree leaves a lot of fruit on the vine when it comes to your differential. We’ve all heard that most cases of uveitis are idiopathic. This mindset can give a false sense of security, especially when the patient isn’t volunteering any additional systemic clues. It is important to be specific when classifying uveitis episodes to reveal any diagnostic clues.

First and foremost, our patient’s case of anterior uveitis should be classified based on its course of approximately four weeks, which makes it an acute episode, or AAU. Suddenly, our differential opens up.

It’s been estimated that up to 50% of AAU cases in Caucasians are HLA-B27-linked.1 Going a step further lends even more weight to the clinical suspicion of an underlying process. This case is a bilateral AAU, which is extremely unusual. According to one study, bilateral, simultaneous-onset AAU accounted for only 1% of uveitis patients over a 20-year period.2 Of the 1%, idiopathic disease accounted for about 30% of cases; the rest had an underlying source.2

While HLA-B27 is the chief source of unilateral AAU, it is distinctly less common in bilateral disease, accounting for only about 9% of patients.2 Post-infectious, usually following a bout of strep throat, and drug-induced uveitis were by far the most common causes.2 HLA-B27-linked disease and tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) were less common but still occurred.2 TINU was a particularly interesting differential in this case, as the patient was young. A separate review found that while TINU only accounted for 1.7% of uveitis patients overall, it accounted for 32% of those who had bilateral AAU and were under the age of 20.3 Another small series found TINU in 60% of children with bilateral AAU.4

Uveitis in the setting of acute tubular/renal dysfunction has been infrequently reported since the mid-1970s. The mechanism, like many systemic inflammatory processes, is somewhat murky. The disease has been linked to previous infections, autoimmunity and, most commonly, drugs (primarily antibiotics and oral non-steroidal agents, though approximately half of cases have no risk factor).5

In most cases of TINU, uveitis follows the renal disease, but approximately 20% of the time, it may precede systemic pathology, sometimes by as much as a year.5 While recurrence of uveitis is common, long-term visual prognosis is good. Kidney disease tends to resolve completely with treatment, and renal function remains good.5

Given the patient’s disease, age and health history, we ordered HLA-B27, urine beta-2 microglobulin, urinalysis and antistreptolysin O titer testing. Of these, only beta-2 microglobulin was positive, yielding 1,997mg/dL compared with the normal range of 0mg/dL to 300mg/dL. This test is a good marker in identifying renal dysfunction, even with normal renal function results, and correlates with TINU in patients with uveitis that matches the profile of bilateral AAU. The test is so sensitive that the authors of one review theorize that with the correct patient and uveitis profile, it may be able to altogether replace renal biopsy, the historic standard for disease confirmation.4

Given the likelihood of this underlying disease, the patient’s uveitis was treated in our office, but he was referred to pediatric nephrology for further evaluation.

This case illustrates the diagnostic utility of fully classifying uveitis. Failing to understand that bilateral AAU is an unusual class and is often associated with systemic pathology may prompt an OD to opt out of further workup if a patient’s review of systems is negative. Recognizing the uniqueness of this case, we pivoted to an appropriate differential, ordered a reasonable series of blood work and got the patient to a subspecialist to monitor kidney function for the best outcome.

| 1. Mapstone R, Woodrow HC. HL-A 27 and acute anterior uveitisi. Br J Ophthalmol. 1975;59(5):270-5. 2. Birnbaum AD, Jiang Y, Vasaiwala R, et al. Bilateral simultaneous-onset nongranulomatous acute anterior uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(11):1389-94. 3. Mackensen F, Smith JR, Rosenbaum JT. Enhanced recognition, treatment, and prognosis of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(5):995-9. 4. Mackensen F, David F, Grulich-Henn J, et al. Urinary beta-2 microglobulin levels reveal a high incidence of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitist syndrome (TINU) in children with sudden onset, bilateral, anterior uveitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3901. 5. Mandeville JT, Levinson RD, Holland GN. The tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;46(3):195-208. |