|

A 56-year-old female was sent in for a cornea evaluation by her primary optometrist. He was concerned by the progression of an increasingly severe keratitis in her right eye. Treatment was initiated four weeks ago with topical trifluridine 1.0%. When the eye didn’t respond, topical tobramycin 0.3% solution was added. Though the patient had significantly reduced vision, she was not in any pain. She had undergone cataract surgery uneventfully on both eyes three years earlier and only wore progressive lenses for reading purposes.

When corrected, the patient’s vision was “hand motion at five feet” OD and 20/25 OS. There was no improvement with pinhole testing on the right eye. The patient had a full range of motion, but full evaluation of pupils and confrontation fields was not possible due to poor direct views of the right pupil and markedly reduced visual acuity (VA), though a consensual response of the left pupil when light was applied to the right was present. Her intraocular pressures were 20mm Hg OD and 8mm Hg OS.

|

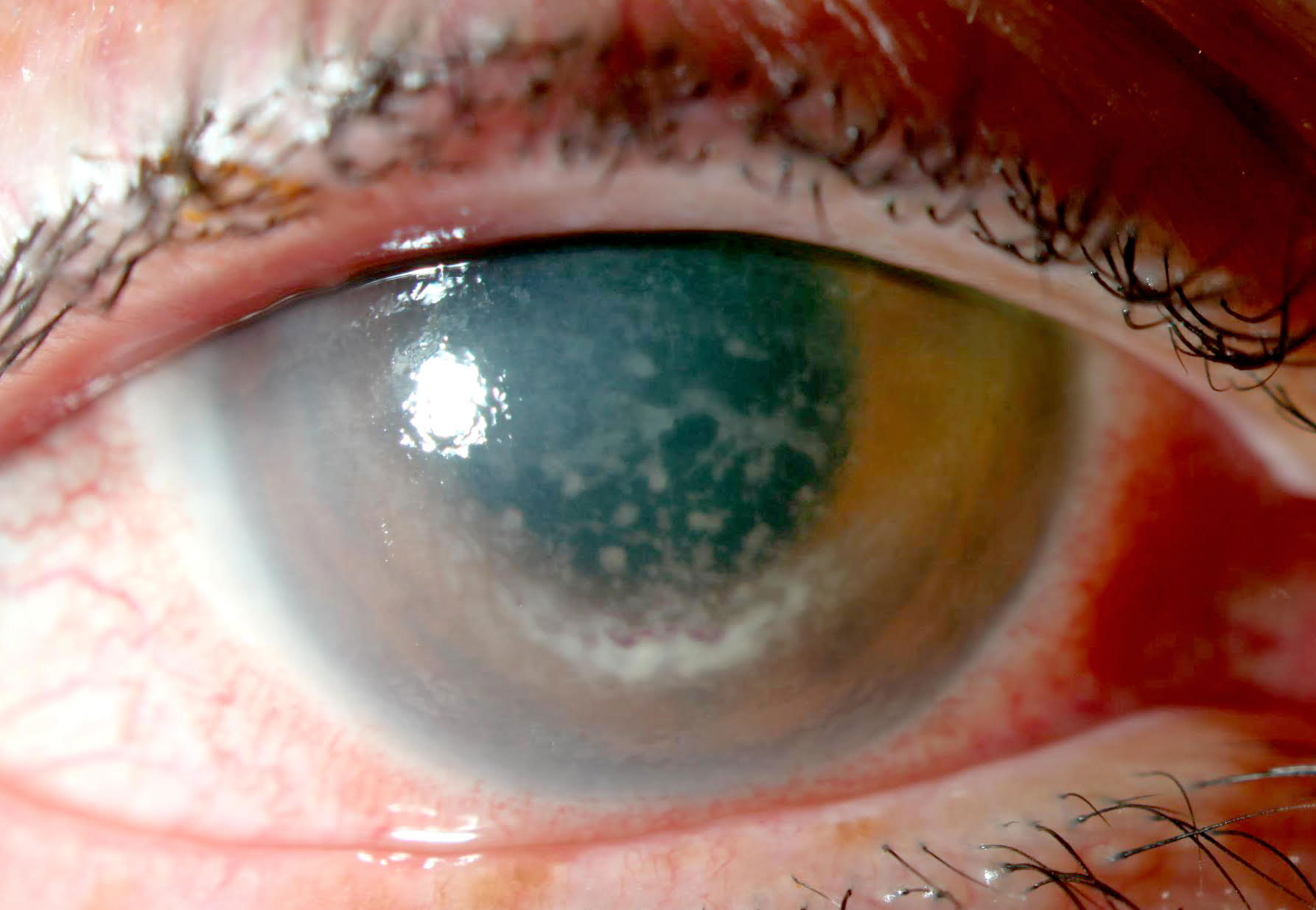

| Intense endotheliitis with placoid and partial ring precipitation of white and red blood cells on the corneal endothelium. Click image to enlarge. |

Preliminary Testing

The patient’s exam showed 1+ lid edema, 3+ injection of the conjunctiva, a superior superficial crescentic marginal infiltrate from 11 o’clock to 2 o’clock, 2+ diffuse epithelial edema and 4+ granulomatous keratic precipitates in a partial ring distribution. Her endotheliitis was intense enough to cause some red blood cells to precipitate as well.

Views of the anterior chamber (AC) were limited, but 1+ to 2+ white cells were graded, the iris was normal without segmental atrophy and the patient’s intraocular lens was in a good position. The full dilated exam showed a grossly normal but poor view of the optic nerve, retinal vessels, macula and retinal periphery due to poor corneal optics. The fellow eye was unremarkable with the exception of pseudophakia.

|

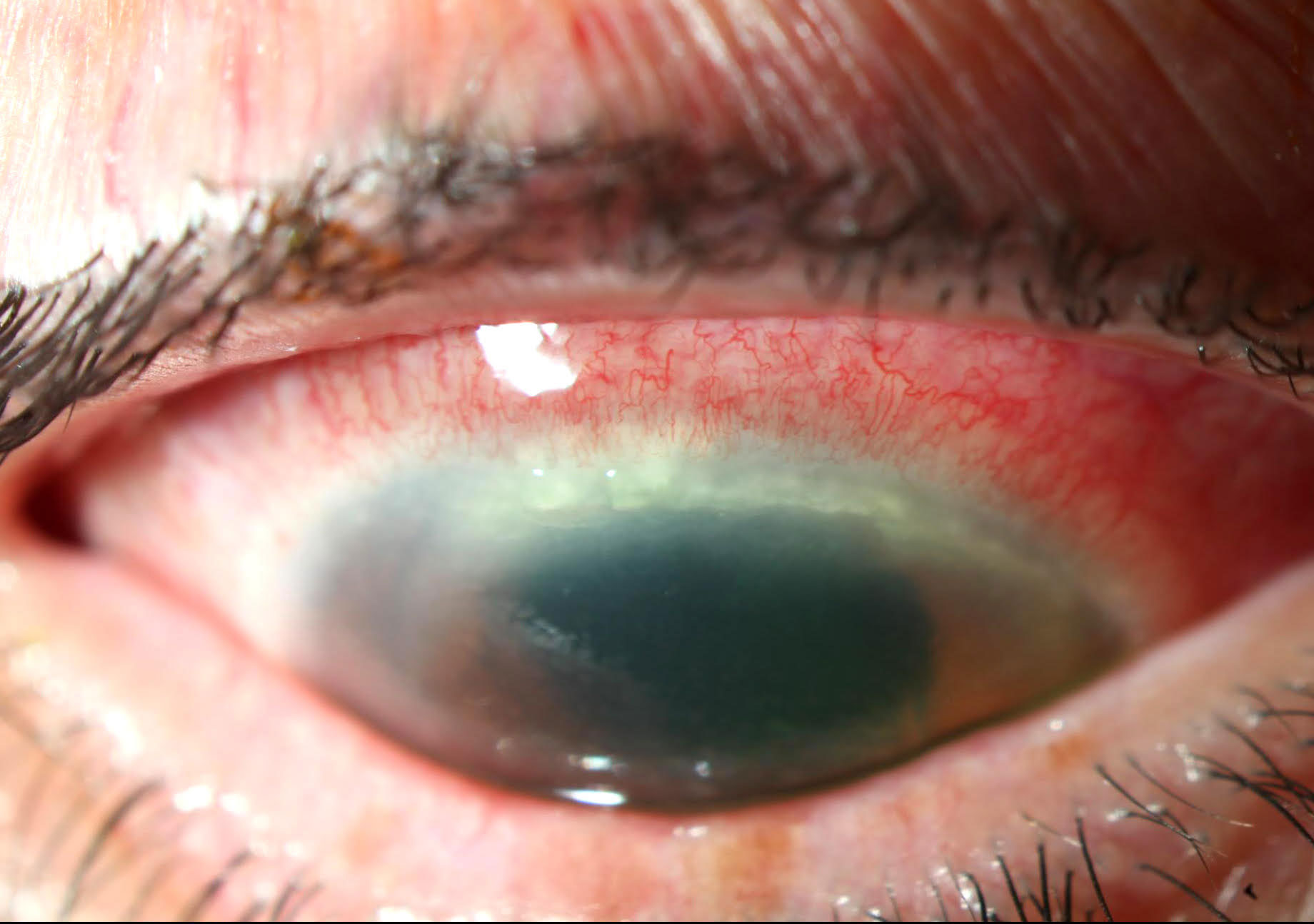

| Superficial peripheral keratitis. Click image to enlarge. |

Problems and Solutions

Marked unilateral keratouveitis/endotheliitis in an adult without any other risk factors is most likely herpetic in origin, so I questioned the patient about a history of herpetic eye disease, which she denied, and cold sores, which she had developed somewhat frequently in the past.

Though the peripheral keratitis was unusual for the diagnosis (and would be more typical of herpes zoster keratouveitis), my working diagnosis was severe diffuse herpes simplex virus (HSV) endotheliitis and uveitis, as the patient had no known history of zoster-based periocular infection. She was placed on homatropine 5% BID, Durezol (difluprednate, Novartis) hourly and oral acyclovir 400mg five times per day and scheduled to follow-up the next day. She was also instructed to discontinue topical anti-infective medication usage, as I felt that after being dosed for about a month, they might be causing superficial stress to the cornea and contributing little therapeutic value.

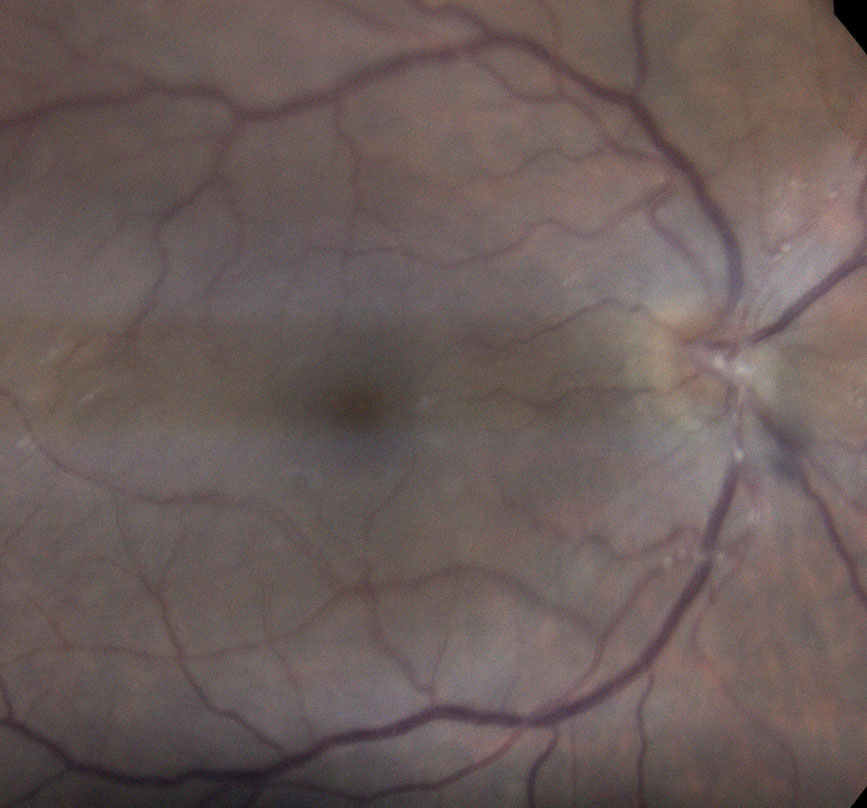

At subsequent follow-ups, we could see that the patient’s corneal and AC pathology was slowly responding to therapy and vision was gradually improving. As corneal optics improved, so did posterior segment views. With these better views, it became apparent that the patient’s posterior segment was also involved to some degree. There was mild vitritis, an asymmetrically mildly hyperemic nerve and a small amount of segmented columnar occlusive material in the primary and secondary retinal arterioles.

|

Improvement in corneal involvement after one week of aggressive therapy. Click image to enlarge. |

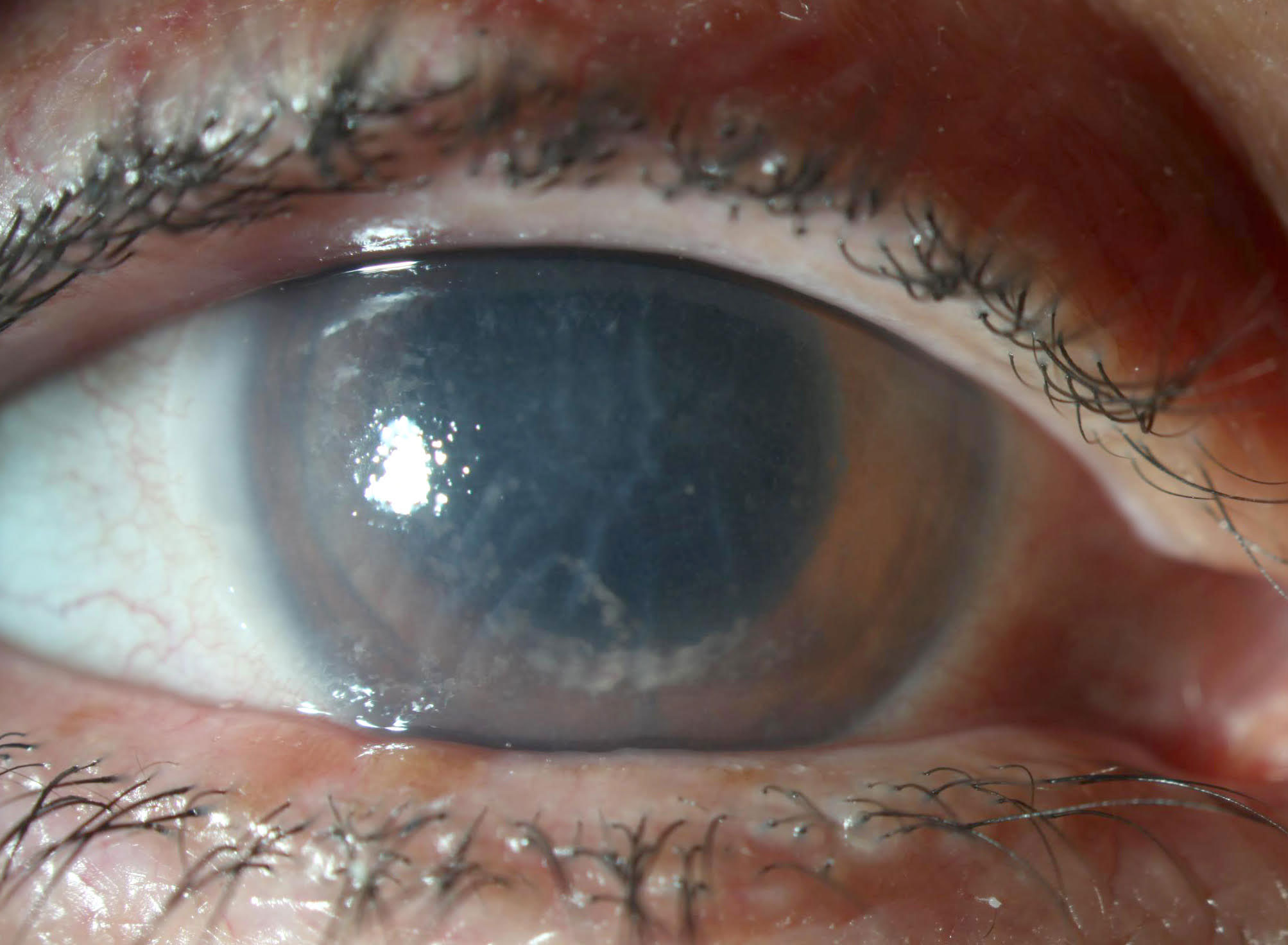

Given the previous diagnosis and now posterior involvement, acute retinal necrosis (ARN) needed to be considered. ARN is a rare pathology caused by herpes viruses that produces a diagnostic triad of edematous necrosis of the retina, occlusive vasculitis/arteritis and vitritis. It carries an extremely negative prognosis—it’s estimated that between 20% and 85% of ARN patients develop rhegmatogenous retinal detachment and nearly 50% of patients end up with a best-corrected VA of 20/200 following the condition.1 Due to the severity of the possible problem and its location in the posterior segment, the patient was maintained on topical therapy and referred to the University of Washington Uveitis Clinic.

At the clinic, posterior involvement of the patient’s uveitis with diffuse retinal vessel leakage, subclinical retinal edema and nerve head leakage was confirmed. The specialist described the arteriolar involvement as Kyrieleis plaques, which are a source of retinal vasculitis associated with ARN, tuberculosis, syphilis toxoplasmosis and Mediterranean spotted fever. Serology tests for these pathologies were run and subsequently found to be negative.

The primary diagnosis of HSV keratouveitis with possible early ARN was maintained. Given the absence of zonal retinal necrosis, a firm diagnosis of ARN was not made, so its treatment protocol, which involves prophylactic vitreoretinal surgery, was not followed. The uveitis facility added a modest dose of oral prednisone with a protracted taper and asked us to schedule follow-ups every six weeks.

|

| Posterior segment involvement shows occlusive arteritis of the primary retinal arterioles. These Kyrieleis plaques are associated with ARN. Click image to enlarge. |

Outcomes

After six months of follow-up and gradually tapering therapy, the patient’s panuveitis fully resolved. She now corrects to 20/20 and is very pleased with the outcome.

This case is a good reminder of an important clinical pointer. While the scope of possible pathologies of herpetic eye disease is wide and the vast majority of cases only involve the anterior segment, the disease’s worst manifestation involves the posterior segment. Therefore, periodic posterior evaluation of these eyes is necessary. Though it is easy to focus only on the anterior exam when working with impressive cases of anterior uveitis, the clinician needs to recognize that these pathologies should not be presumed to only involve the anterior segment. Paying equal close attention to the posterior segment is critical to catch panuveitis, which is associated with more profound and longer-lasting vision loss.

| 1. Schoenberger SD, Kim SJ, Thorne JE, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute retinal necrosis: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(3):382-92. |