|

Fitting patients with GP lenses is a fairly routine task these days that may require speaking with a lens consultant. When seeking consultation regarding any type of GP lens, it may help to keep the following information at the ready:

|

|

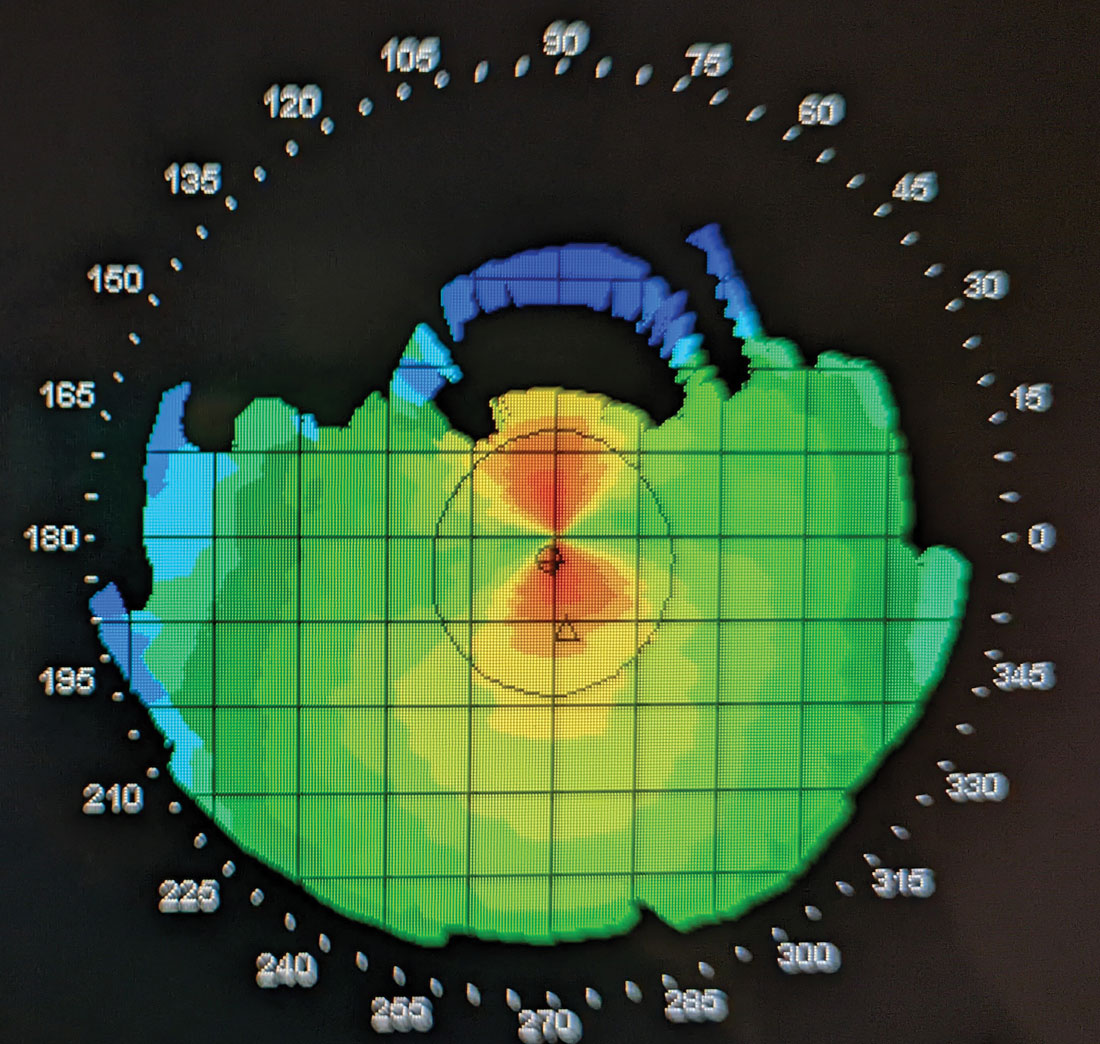

Fig. 1. An unreliable topography map. The superior portion of the topography shows missing data. Despite repeated attempts, no improvement could be made and this topography was successfully used to rehabilitate a poor-fitting lens; however, I would not recommend relying on such subpar maps. Click image to enlarge. |

1. Your lab account number. Yes, they can look it up, but it’s often faster if you have it handy. Watch out for Ls that look like Is and Os that look like 0s! Consider making a list so they’re all in one spot.

2. The name of the patient you’re fitting, but also their birthday. There are probably a lot of John Smiths in the lab’s database. Maybe only one Johnn Smitth, but maybe that was a typo. The date of birth helps sort out any administrative slip-ups.

3. If making an exchange, have the previous invoice number. See No. 1. Yes, they can look it up for you, but saving time in the long-term is the strategy here. The faster you get off the phone, the faster you can see the next patient (or go home). If you can’t locate the original invoice, you can often request a copy via customer service or the lab’s website login.

4. The type of cornea you are fitting. Is it normal, keratoconic (and what shape of cone?), pellucid, post-trauma, etc.? Bonus points if you have a topography map. Double bonus points if you have a tomography map for some cases. Super double bonus points if you have profilometry, not to say that you need that instrumentation all the time; keratometry values (auto or even manual, if yours is still kickin’ it) will often suffice to start.

a. Also, garbage in = garbage out. Make sure your maps are quality. Use artificial tears and take several maps, choosing the best, most reliable ones.

b. Consider this your public service announcement on when to fit a scleral vs. a corneal GP lens. On your elevation map, if the height differential along any given meridian exceeds 350µm, the patient may be a better candidate for a scleral lens design.1 Should you neglect to assess this and place a GP lens on a cornea with an elevation difference >350µm, you will quickly find the lens teeter-tottering on the cornea. The fit will likely be poor, the patient will be unhappy and you will be frustrated.

5. While you’re at the slit lamp, take a look at the corneal size and measure the horizontal visible iris diameter. Yes, your topographer can do this, but it may not be accurate. This information can help you troubleshoot any number of lenses! For corneal GPs, it can help you determine starting overall diameter and optic zone size.

|

|

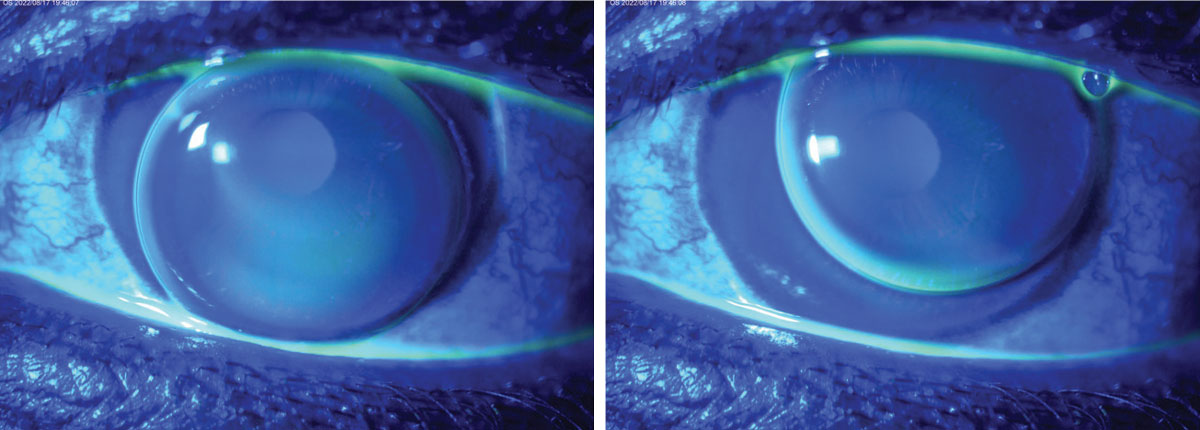

Fig. 2. Assessing this aphakic GP lens was more challenging because the dynamic fit meant it was lid-attached on one blink and interpalpebral on the next blink. Click image to enlarge. |

6. Refractive information. It’s important to have the following on-hand: refraction, the add (if presbyopic) and the overrefraction (push plus!) if you have a lens on-eye. Otherwise, you are likely to have a disappointed patient.

a. If you find an overrefraction, think critically. Do you want to incorporate it? Did it truly improve the patient’s vision or visual efficiency?

b. If you have a sphero-cylindrical overrefraction, is it large enough (typically >0.75D cyl) to make changes to the lens, and does it also improve VA? Is the lens flexing?

c. If fitting a multifocal lens, remember to do your overrefraction in free space, with loose lenses, assessing one eye at a time. Anything you put over the patient’s eye at distance will ultimately affect their near vision.

7. If you’re fitting diagnostically, what parameters did you use to fit? Which lenses from the fitting set? By the way, did you verify those lenses? And maybe you should just verify the entire fitting set while you’re at it...it’s hard for a consultant to help you if your diagnostic lenses are mixed up (those laser-engraved lenses are a life-saver!) and “nothing makes sense.” Record the lens base curve (and/or sagittal height), power, diameter and other customizations. Some laboratories have fitting assessment forms you can download from the website for this purpose (especially helpful with toric haptic/quad specific scleral lenses).

8. What did the sodium fluorescein pattern look like on-eye? Did you examine it with a Wratten filter? Bonus points if you have photos. Double bonus points if you have a video to share. A quick description of the fit would include if it is interpalpebral or lid-attached; whether the lens is centered (and, if decentered, which direction and how much; that is, where is the lens relative to the center of the cornea?); the amount of movement on blink; movement on lateral gaze; and the fluorescein pattern assessment.

a. Regarding movement, it helps to know whether the movement is consistent (does the lens go back to the same place after the blink?). Recall that lenses always rock or move along the steepest meridian of the cornea. Don’t know where that is? Check your topography map.

b. Photos can be helpful here, but also can be misleading. Remember a photo is a snapshot in time. A fluorescein pattern assessment is often dynamic in nature.

9. If fitting a scleral lens, it’s good to know the parameters of the lens you’re looking at. This includes whether it has a toric landing, front surface toric, oblate profile, multifocal optics, edge vault, etc.

|

|

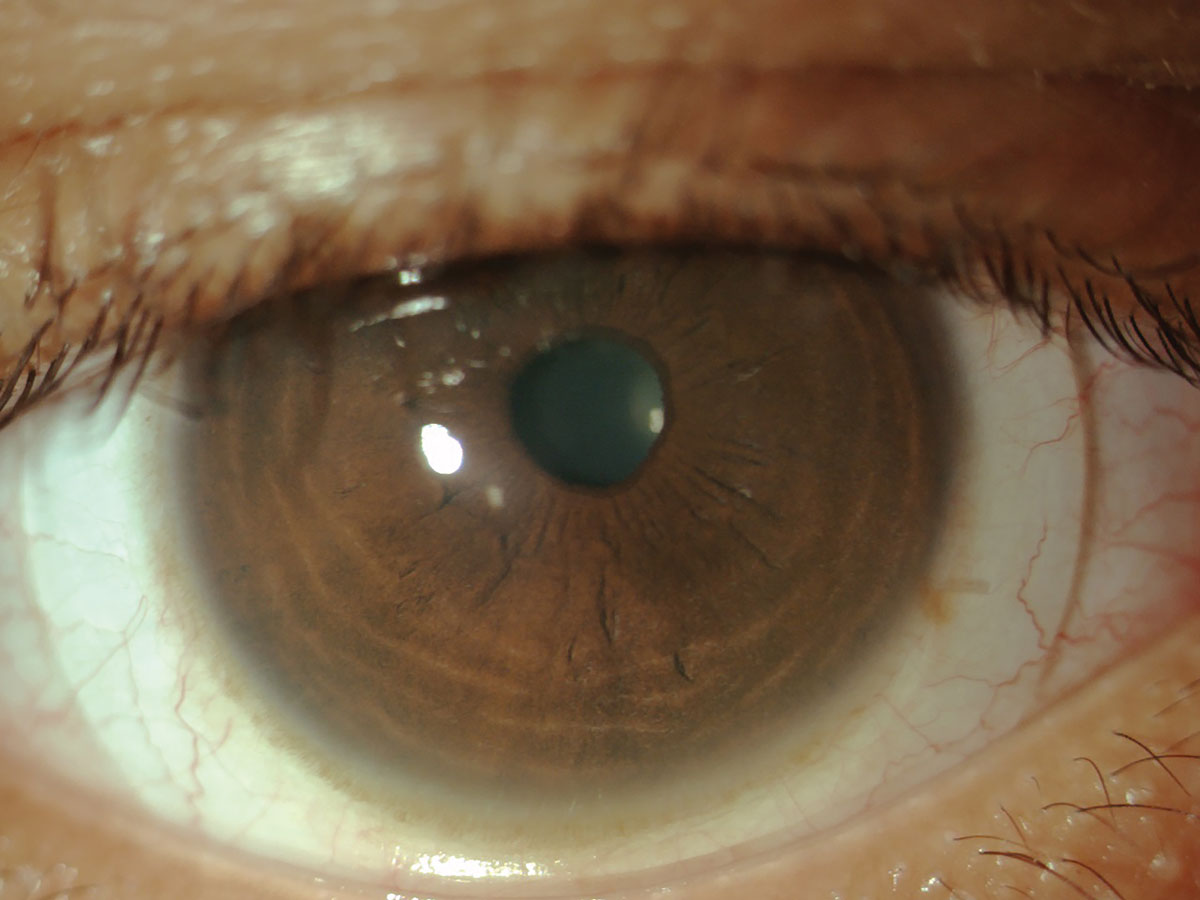

Fig. 3. In this scleral fit, it was helpful to note that the markings were at the 4 and 10 o’clock position. Click image to enlarge. |

10. When describing the edge appearance to the consultant, use clock hours to describe the edge appearance, noting any blanching/impingement or edge lift off. When analyzing that pattern, does it appear asymmetric (and maybe therefore toric)? That is, does it appear to be lifting off in one meridian and too steep in the opposite meridian? If so, the candidate may need some toricity in the edge of the corneal lens or in the landing zone of the scleral lens.

11. When assessing scleral lenses, there are a couple basic things to consider being more detailed about: location and time.

a. With location, it’s best to estimate the central tear reservoir thickness centrally but also look in the mid-peripheral part of the central zone (where there may be less clearance if the cornea is oblate or more clearance if the corneal is prolate), as well as in the transition (read: limbal) zone. Is there a little sliver of sodium fluorescein over the limbus as you transition your slit lamp beam to the sclera? It can be helpful here to note the apex of the cornea or highest point of elevation (and it’s not always central). This would be a key location to assess the tear reservoir under the lens.

b. It helps to assess sclerals over time—at the time of application, 30 minutes later and after four or more hours of wear are some time points to consider. At the time of application, the central tear reservoir will tend to be larger than it is after lens settling has occurred. It is helpful to note the time of lens application in your medical record and you can compare that to the time any assessments (slit lamp or anterior segment OCT) of the central tear reservoir are made.

12. Are there any markings on the lens? If so, what and where? Are they stable? This is where it can be super helpful to have a photo of the lens in case you forget. If you are fitting front toric GP lenses, provide the direction of rotation to the lab. Using a standard clockwise or counter-clockwise notation is helpful for cylinder axis orientation.

I don’t write all of this to tell you I am a perfect GP lens fitter. In fact, my email exchanges with consultants often bring up these exact requests. My goal is to save you some time so you don’t have an endless thread of questions in your inbox. Now, go see your next patient!

1. Caroline PJ, Andre MP. Initial Selection of Corneal Versus Scleral GP Lens. Contact Lens Spectrum. April 1, 2015. Accessed March 13, 2024. www.clspectrum.com/issues/2015/april/contact-lens-case-reports. |